Contexts

In Naples, Vassily Barkhatov staged an impressive performance, with the set design and the development of the chorus filling the space, even though, to the despair of the regulars, China was absent.

Which China, by the way ? That of Gozzi, who knew it only by hearsay and the objects imported to Venice that filled the patrician residences, or that of our fantasies fuelled by Van Gulik's novels and the pictures of Empress Tseu-Hi (or Cixi), or the supposed barbarity of a China that between 1899 and 1901 had terrorised the colonial West that occupied (and exploited) the country during the Boxer Revolt, which ended with the victory of the 'allied' nations (France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States, Japan, Italy, Austria-Hungary and Germany).

In any case, Turandot's China is a China of mental representation, an imaginary space that has nothing to do with reality, a China of fables, fuelled by our own projections and traditions of representation, a China of otherness, almost an absolute otherness, as this story seems to confirm.

If we refer to Gozzi, the 1762 premiere of this 'tragi-comical theatrical fable in five acts' was planned for the San Samuele Theatre, which was small in size, in a setting suited to the Commedia dell'Arte style that Gozzi wanted to contrast with the modern style of his contemporary Goldoni.

The characters in the comedy include Truffaldino, Pantalone, Tartaglia and Brighella, typical of the tradition that gave the tale a light, popular and somewhat sarcastic flavour, while Calaf in the piece is a sort of womanizer.

Gozzi's comedy enjoyed great popularity in the 19th century, starting with Schiller, who translated it and had it performed at the Hoftheater in Weimar, where it took on a more serious romantic tone, abandoning sarcasm and giving more weight to Calaf, who became more romantic and less light-hearted.

At the beginning of the 20th century, shortly before the First World War, Max Reinhardt staged Gozzi's play in Berlin in 1911 (for which Puccini requested photographs) with music from Busoni's Turandot-Suite, then in London in 1913 with a reduction of the (unauthorised) orchestration by one of Busoni's pupils. As for Busoni himself, in 1917 he composed his Turandot in two acts based on his Turandot-Suite, which was first performed in Zurich.

The fortune of this story (handed down by the Frenchman François Pétis de la Croix in a collection of stories or supposed Persian stories entitled 'Les Mille et un Jours' (The Thousand and One Days) (1710–1712) continued, especially in Italy and Germany, throughout the 19th century.

At the beginning of the 20th century, in addition to the Boxer Revolt between 1899 and 1901, the story of Turandot seemed to illustrate this 'Law of Murder' cited by the French author Octave Mirbeau in his novel 'Le jardin des supplices' (The Torture Garden), which denounced a kind of universal law that governs all societies, whatever their nature : they are all based on murder. The novel, published in 1899, refers to China, and in particular to the penal colony of Canton, but it concerns all human societies fascinated by blood and torture. The universal slaughter of the First World War would also leave an indelible mark on the threshold of the 1920s.

If Turandot was an inspiring work for composers, Orientalism was also flourishing at the beginning of the 20th century : Debussy was already fascinated by the new sounds he heard coming from Asia, the new instruments (gamelan, etc.) and the way they were used. ) and the use (like Puccini) of the pentatonic scale, but mention must also be made of Bartok, whose ballet The Miraculous Mandarin, inspired by a Chinese story, follows the same chronological path as Turandot (completed in 1924 and premiered in 1926). There is also Die Frau ohne Schatten (The Woman without a Shadow) created in Vienna in 1919, in which the name of one of the characters (Barak) is borrowed from Gozzi's play and in which another of the characters, Turandot's slave Adelma, is the daughter of King Cheicobad (who in Die Frau ohne Schatten is the empress's father – the god Keikobad).

Puccini was in Vienna for the premiere of Il Trittico on 20 October 1920 and had the opportunity to see Die Frau ohne Schatten on 21 October, a year after the premiere. Puccini was very curious about all the music of his time, although Strauss' opera does not seem to have appealed to him.

Finally, mention must be made of Lehár's operetta Die gelbe Jacke (The Yellow Jacket), presented in Vienna in 1923, which Puccini saw in the company of Lehár (it was the first version of what would become The Land of Smiles in 1929). These were common sources of inspiration for the Orientalist tales that circulated.

Anxious to concentrate on the libretto proposed by Simoni and Adami and to draw simple, no-frills lines from Gozzi, he even thought of reducing the drama to two acts (Gozzi's play has five), but his main concern was to propose a humanised figure, in a way humanised through love. "In short, I consider Turandot to be the most normal and human piece of theatre of all Gozzi's other productions. In short : a Turandot through the modern brain…”. This is what Puccini wrote to Adami.

And he wanted an opera that owed nothing to what had gone before, a completely new opera, with a new character, Liù, to take the place of the aforementioned Adelma.

Darkness, then final, grandiose, white and pink scene : Amore !

This is the last sentence of the summary of the libretto (in two acts) he wanted, which ends very humanly with an explosion of love, in a 'pink and white' version quite similar to the finale of a musical for the imagination it presupposes, an ending that Barkhatov in Naples and Guth in Vienna, in a completely different way, accept as a 'happy ending', reserving for themselves the part rewritten by Alfano, less elaborate than the one written by Puccini, with apparently 'easy' solutions that correspond to a 'musical comedy' ending that we seem to hear through this flatter and noisier music, more full of sequins than diamonds, but whose final meaning seems to correspond to Puccini's desire. On both sides, the tale ends with an explosion of love.

The Viennese production of Turandot begins in the silence interrupted by the ticking of a clock, which can be experienced as the expression of time that inexorably advances, but also of time that remains, like the ticking of radio or television games that set a deadline and mark the approach of the end. As if announcing a resolution, before the story has even begun.

So it all begins with this silence punctuated by the ticking of the clock, followed by the cadenced steps of the chorus taking its place on the proscenium, facing the audience (and the conductor, for convenience).

While Barkhatov's chorus is part of the action, surrounding the protagonists, Guth's chorus is outside, in a confined space of the proscenium, like a stage under the stage, under a raised floor, taking no part in an action of which it remains a spectator and from which it will always be kept at a distance. In fact, he will be outside, invisible, or just passing by (in the case of the children's choir). The story told by Guth is an intimate one, beginning with the vision of high white walls from which a shadow (Video by Rocafilm-Roland Horvath) can be glimpsed, moving vaguely as a man emerges from a trapdoor and encounters only closed walls and doors, but through the back wall the vaguely ghostly shadow takes on the sketched, ghostly form of the woman who will become obsessive and whose blurred image extends a hand, The man responds by also extending his hand towards her.

Act I

This prologue, without music, sets the scene for a story that will never change : a shadow protected by a wall extends a hand and a man answers : something is born.

And immediately the door opens, and shyly the man peeps out and enters, jumps into the world behind the wall, just as Alice jumps into Wonderland, jumps into the land of his dream.

The music begins.

The wall as it rises reveals a new space, a white box enclosed by high walls, with seats in the first act as if in a sort of waiting room, a gigantic door at the back and smaller ones at the sides, and a matching staircase with a mysterious bottom. Everything is monochrome, while the staircase to the underworld is covered with a world of flowers, like a colourful outer space (which we can barely make out), while the play area is uniform and aseptic.

We find again the man from the silent prologue, this time in front of a monumental door, and on one of the chairs another character, rigid, waiting and absent.

And then everything starts to move, with the man (we have understood that it is Calaf) moving without ever communicating, as if two parallel worlds that cannot interpenetrate are being shown.

On one side a man who looks perplexed at these movements, on the other people dressed (costumes by Ursula Kudrna) all similarly (pale green dresses, pink buttonholes, uniform red wigs and spectacles) an asexual world made up of men, women and children arranged by size and difficult to distinguish. Movements take place without taking Calaf into account, except to prevent him from moving towards the others.

The entrance of Timur, a blind man, who enters through one of the side doors designed like the metal doors of a wardrobe, as if an invisible mechanism were put in place to make him appear on stage 'to play his part', as if an invisible mechanism were put in place to interfere with Calaf.

This almost mechanical ballet, regulated by a real choreography (of Sommer Ulrickson) (the characters who move are in fact dancers), shows that the movements, the costumes, the organisation, everything about the unfolding of the first act reveals a mechanical and ritualistic system, organised around death, or rather, to be precise, around decapitation – a kind of world of living automatons… that offers itself as a spectacle to Calaf. A system whose sole purpose seems to be not to decapitate, but to collect heads (well-calibrated, given the way the Prince of Persia's is measured) in labelled and filed boxes, as in a natural history museum. These boxes are stored behind the side cupboard doors, but the proscenium chorus members are also seated on them. It is a system whose time is marked only by the rituals of performance, punctuated by the clock whose ticking is behind the prompter's pit we mentioned earlier. In this world, time is marked by the blade of the sword and the hands of the clock : the mechanics of destiny to be added to an anthology reminiscent of Mirbeau's Torture Garden, already mentioned.

The system shown (and disassembled) by Claus Guth is perhaps Turandot's mental space, mediated by a tale and thus allowing all the licentiousness of the tale, and finally precisely because it is a fairy tale and since Bruno Bettelheim has been there, it allows a plunge into psychoanalysis, all the more so because the setting (the front door at the back) recalls Sigmund Freud's house at Berggasse 19 in Vienna. Guth, whose interest in the complexities of the psyche is well known, obviously intends to play with all these levels.

Thus the elements that enter the scene in the first act appear to be a ballet, a pantomime (so much in vogue in the 18th century, at the time of Gozzi's play) whose purpose would be to dissuade Calaf from approaching almost apotropaic figures, the figure of the father, but also that of Liù who is not a being of flesh, But she too is a multiplied figure, as are the figures of the officiants in wigs, a figure followed by four shadows that follow her, as if to dilute her humanity and transform it into an abstraction that is also cast to dissuade Calaf from going further.

The figure of the Prince of Persia is the other man sitting awaiting execution, a figure of failure and at the same time, for Calaf, a figure of solidarity, the only 'humans' in this room where all the others (and even his father who emerges from a side door of the wardrobe, dragged by the red figures, just like Liù and her projected shadows) seem like abstractions thrown in his path, which he is prevented from approaching or touching.

Of course, all of this only has a particularly elastic relationship to the distant real, as do the fantasies and mental representations, fairy tales and China seen in Gozzi and Puccini. What Guth is telling us is the relativity of context when the stakes are elsewhere.

We have seen Calaf arrive in a space in which a shadow has appeared to attract him, we have seen Calaf respond to this attraction, and arrive in a world made of successive walls, as if it were once clear (and it is clear from the silent prologue) that this story is not Calaf's story to Turandot, but a story of two, a story of a couple, it was necessary, as in The Magic Flute, to go through trials to conquer his paradise, as Lancelot, to go through trials to conquer his Love.

Turandot as a rescue piece, with the difference that the young woman was not locked up in a prison, but locked herself in to protect herself from her own desire, her own fears, and the only man who could conquer her, that is, love her.

Thus, in this act centred on Calaf, dizzying images follow one another in order to make him desist, such as the servants carrying the severed heads out of their boxes, such as the way a gourd is cut to check that the sabre blade is sharp when the executioner's servants sing

Con gli uncini e coi coltelli,

noi siamo pronti a ricamar

le vostre pelli !

(With hooks and knives,we're ready to recamar

your skins!)

or the strange waltz of a ghostly Turandot stepping out of her space (the gigantic door) to begin a strange dance with a decapitated man who is smoking a cigarette when the chorus begins Perché tarda la luna (Why tarry for the moon) with that obviously ironic distance that is not lacking in Guth's work, We see it in Calaf's surprised and somewhat frightened reactions, just as we see it when the servants hold up a severed head and march to the moonrise, the signal of the coming torture. Calaf's facial expressions, sometimes fascinated, sometimes surprised, but not necessarily or always frightened, as from below emerges the chorus of children, dressed as servant apprentices (same wig, but with shorts and backpacks like the children, the last of whom holds a paper aeroplane), in a strange, magnetic procession singing

Là, sui monti dell'est,

la cicogna cantò.

Ma l'aprile non rifiorì

(There, on the mountains of the east, the stork sang.

But April did not blossom again)

The world repeats and reproduces itself, in the hope of spring.

The second part of the act then begins, with the sacrifice of the Prince of Persia. At first, the ministers walk towards Calaf seated next to him as if in a waiting room, but they are shown the error of their ways and drag the Prince of Persia through the door, after making him sign a declaration (always this idea of system and administration, obviously reminiscent of the administration of death that every visitor to a concentration camp discovers with surprise and horror).

The ritual of death is underlined by the appearance of Turandot's shadow on the wall, holding out her hand as at the beginning, but with blood dripping, and then the body and face of the princess appear more clearly for the first time, deciding Calaf,

La vita, padre è qui !

Turandot ! Turandot ! Turandot ! (Life, father is here!Turandot ! Turandot ! Turandot!) while the ministers try to dissuade him and the Prince of Persia is executed and his head presented.

In the finale of the act, where everyone tries to dissuade Calaf, it is the ghosts that reappear, decapitated heads and men evoking their love for her beyond death, prompting Calaf to shout : “No ! No ! Io solo, l'amo!" (No ! No ! I alone, I love her!), which is the driving force behind his appeal, despite the dance of the others, ministers, Timur, Liù, who try to distract him. While the shadow is firmly on the wall and the scent, which envelops the beings and affirms an impalpable yet palpable presence, has invaded the space.

The way the scene is constructed, the impression is twofold : on the one hand it is the torture of the Prince of Persia that finally unleashes Calaf's will, on the other he is the sole bearer of the love that will transcend trials and death. It is the vision of death that shows him the path to life, a path discreetly traced on the floor beneath the monumental door, the same carpet that covers the central staircase, the flowery carpet of life…

Thus, this first act, centred on Calaf, is the product of a vision born of a glimpsed shadow, as in a fairy tale (this is how it seems to begin) that turns into a nightmarish space for the vision it offers Calaf of the mechanism of death of the world built by Turandot, with the side steps, the shifts that are those of dreams, absurd and at times comical, like those heads we cannot believe (we are in the theatre) but that refer to other terrible realities that were neither in dreams nor in fairy tales, with the princess Turandot, the fruit of an imaginary or mad desire, who becomes all the more fragile the more she protects herself, finally allowing her body and no longer her shadow to be seen through an opaque screen, as if it were she who created the conditions for the trap into which she herself would soon fall, or as if Calaf's desire no longer materialised the vision of death that overwhelms this first act, but allowed him a glimpse of the space of life offered to him by love.

Act II

If the first act is that of Calaf, the second is that of Turandot, built around two scenes, that of the ministers Ping, Pang, Pong and that of the riddles, which makes up the rest of the act. The first scene is one of the opera's wackiest moments, with the commedia dell'arte characters caught up in the mechanics of death and the nostalgia for personal paradises, while the second scene (of the riddles) is the great spectacular scene, the 'moment' that has to precipitate everything, the cinematic moment, thus the focal point.

While the first scene is treated no differently from other visions, albeit with the specificities of Guth's vision, the second, that of the riddles, is completely different from the usual, since from the large crowd scene we are used to, we move on to Turandot's 'den', in her bedroom symbolised by the bed, at the foot of which lie four 'dolls' accompanying her, a sort of bedroom of a grown child where she is about to play her favourite game, that of riddles, under the reproachful eye of her father.

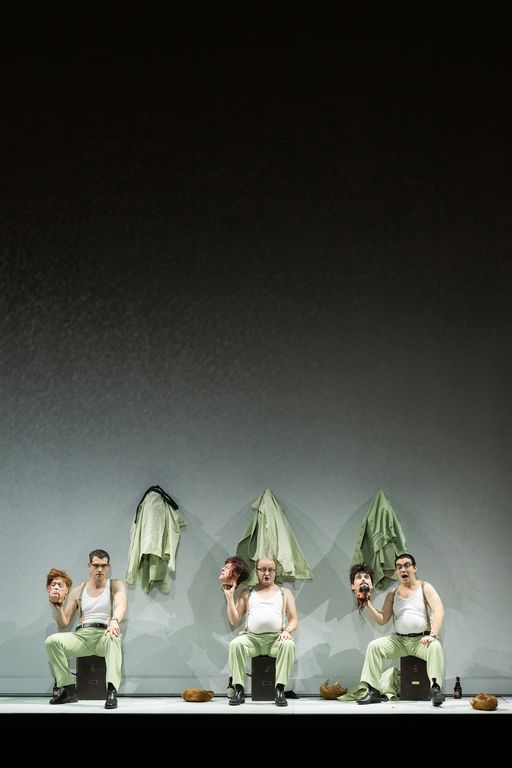

The first scene, as we have said, presents ministers Ping, Pang and Pong in their usual roles, in a kind of pantomime that does not deviate from the usual patterns of this scene, coordinated movements, together or alternating, choreographic games that we might see in Zeffirelli's or others' productions, The only difference is that they are dressed in the same general uniform, a pale green double-breasted suit with a pink buttonhole, a red wig and glasses that make them all look like civil servants of a friendly(?) North Korea. The three ministers manage the gruelling and terrible daily life of death administrators, while arranging the boxes containing the severed heads.

Then things change when Ping conjures up his 'little corner of paradise', far from the Kafkaesque administration they must endure and run, with I have a house in Honan followed by Pong I have forests, near Tsiang, and Pang I have a garden near Kiù. A moment of suspension (musically very marked) that Claus Guth emphasises by making the three 'automata', the three puppets, become three simple human beings who, in evoking their little corners of paradise, shed their costumes, their wigs and their glasses to become ordinary, of that common humanity of which they are deprived by the machine devised by Turandot. But it is only a fleeting moment, for after conjuring up a list of decapitated

Uccidi… e estingui…

Ammazza…

Addio, amore !

Addio, razza !

(Kill… Kill… and extinguish…

Farewell, love !

Farewell, race!)

reality catches up with them when they hear the beginning of the ceremonial call to order and service

Andiamo a goderci

l'ennesimo supplizio !

Let us go and enjoy

yet another torment !

The next scene, the second and last of the act, is that of the riddles. We know the value of riddles in mythology, in particular from Oedipus, who answers the riddle of the Sphinx, the only example in Greek mythology of a hero ridding himself of a monster with the power of his mind, a false victory as we know, for Oedipus marries Jocasta, the queen, as the liberator of Thebes, but it turns out that Jocasta is his mother, and here we come to Freud's shores, especially as the setting is reminiscent of the door to Freud's flat in Vienna, where we see a complex grid-like security system.

The enigma conceals (or preludes to) a psychic labyrinth. In this case, the Sphinx is Turandot, who plunges her people into this permanent law of murder and plunges the state into a kind of totalitarian system. By deciphering the riddles, Calaf will be in a sense himself a liberator, like Oedipus.

The set design makes this clear when the partition wall rises. A monumental door equipped with a complex security system makes us realise it is the other side of the Act I set, which was only the antechamber to Turandot's bedroom, a bedroom where everything happens.

The first image says it all : Turandot is in bed, crouched, pensive, sullen, with sleeping dolls at her feet and a maid beside her scrubbing the floor to remove a bloodstain.

Everything happens : protected by her door and her bed, Turandot dictates riddles from her bed and has the princes who have failed beheaded before her.

It is, of course, a highly symbolic scene : in the famous diptych Io ti amo io ti uccido (I love you I kill you), Turandot chooses 'I kill you' to protect herself from 'I love you'.

With her long white hair, she reminded me of Loreley, the Rhine-maiden who lures the sailors captivated by her singing and who crash against the rocks. She is the ideal, the dream, the bewitchment and the trap.

She calls herself white, and she is white like snow, like ice, like the untouchable purity of a snowy landscape. But in her large room, surrounded by her four pink dolls, she is also completely isolated, in a structural, perhaps chosen solitude, almost an abstraction

The scene of the three riddles is thus carefully ritualised by Guth. No people, rejected outside, commenting without seeing, an almost abstract people. The chorus is not seen again until the end of the opera, which is conceived as a drama behind closed doors. We see some servants, the ministers, Calaf and for a moment the children's chorus, which enters the hall and then leaves. At the same time, the riddle scene takes on a different meaning. It is no longer a 'political' scene, but a family scene, between father, daughter and suitor, while the ministers are the organisers of the test.

Turandot is first and foremost a sullen child in bed, protecting herself with the sheet, protected by her dolls, figures of childhood (on the wall, before she rises to reveal the bedroom, the figure of a little girl holding a doll is projected), as if by showing this eternal childhood, Turandot strengthens her protection : a child is untouchable by essence.

Altoum is identified as the king by the decorative red sash across his costume, and his advanced age by the fact that he immediately takes medicine in a glass (a viaticum) and will always have a handkerchief in his hand in which he spits blood while saying

E il santo scettro ch'io stringo,

gronda di sangue ! (And the holy sceptre that I hold,

drips with blood!)

Here Guth, leaving Turandot to spill blood for a moment, hints that Altoum is at the end of his life and is trying to secure a peaceful succession, hence the grim looks towards his daughter who prevents him from doing so and also towards the bloodstain on the floor, a trace of the previous beheading. Guth introduces a dynastic and political aspect that will be important in the very last image of the opera.

The ritual of the riddles is already a death rite : Calaf is introduced with his hands bound and blindfolded, like a man condemned to death ; the executioner is also introduced and waits, sitting in a corner ; and at the moment of the riddles, the ministers draw a circle of black ashes around the 'accused', while he crouches on the piece of furniture that is also the one used for the beheading. The ritual is not one of riddles, but of execution.

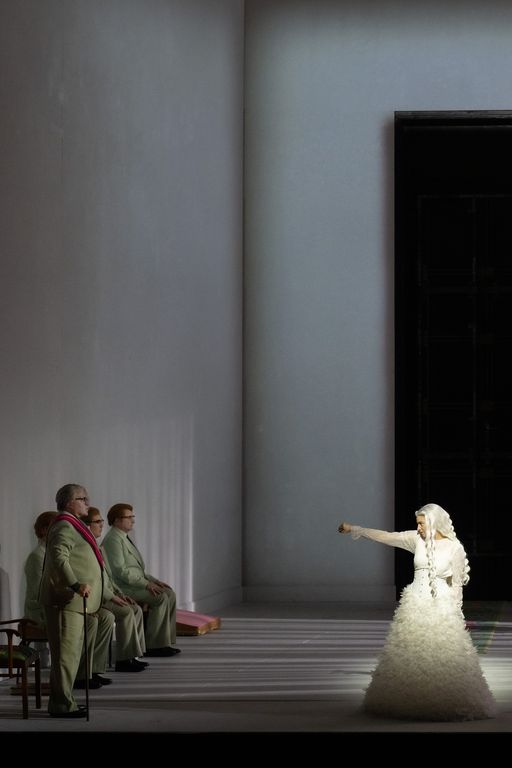

At the moment of the riddles, Turandot is dressed in a skirt of white feathers, like a snow-white bird ; she is no longer the little girl protecting herself in her bed, and Calaf is freed from his bonds.

The whole scene of the riddles does not have the more or less impersonal aspect that it sometimes has (Turandot at the top in the distance asking her questions and Calaf at the bottom answering them in front of the crowd), but on the contrary regulates the scene as an increasingly close dialogue between two characters, and In questa reggia, in which Turandot recounts her story and the reasons that lead her to preserve her purity (her ancestress raped, whose bones she keeps under her bed, exposed by the dolls that surround her), becomes a speech (almost a confession) addressed to Calaf himself. The young woman moves around the room, watching, interpreting, affirming and fearing at the same time. Although the ministers, the emperor and the executioner are present, what we are witnessing is a scene of intimacy between the couple, which Turandot feels more and more, until she is terrified and the lighting isolates the two characters, throwing all the others into the shadows (lighting by Olaf Freese). Turandot lives only with death and memories of death (she brandishes a knife at the end of her aria) because she sees enigmas as an inevitable road to death, while Calaf sees enigmas as the road to life, because they are the road to love.

Each positive answer from Calaf will therefore be a surprise, triggering a series of movements. For each answer, one of the ministers places a black stone, like a lava stone, in the black circle, while Turandot takes refuge with her dolls in the opposite corner of the room, at first more or less dignified (first answer, Hope), then increasingly distressed (but perhaps also increasingly tempted, and thus fearful of temptation). Moreover, Asmik Grigorian's gestures, glances and movements are always ambiguous, like a game played on a razor's edge.

In the second riddle, Turandot begins surrounded (and protected) by her dolls, from whom she frees herself but remains distant from Calaf (unlike in the previous riddle), while the Emperor and downstairs Liù speaks, like a distant figure crossing the proscenium like a breath of inspiration reminding us of what is at stake : love. This provokes Calaf's reaction, who sobs as the dolls return to the opposite corner and Turandot becomes unusually agitated as she poses the final riddle sitting on the bed, then facing Calaf, as if suggesting the answer ('Turandot') to him almost brazenly, with insistent, almost offered glances.

Turandot immediately takes refuge in a corner, protected by her dolls, but here the ritual takes over the exchange between the two, as if they no longer belong to each other : the bed is placed in the middle, it is surrounded by rose petals and now has two pillows, a double bed, and very quickly the consummation must take place : Turandot, covered by the bride's veil (as we dreamt of her in Act I), becomes pleading with her father to avoid being taken by Calaf, taken, offered, delivered. It is a moment of extraordinary intensity, dominated by the singing of Asmik Grigorian, who casts off her veil and returns to being the defenceless child who takes refuge along the bed, which has become a defensive barrier in an image of singular power.

The act ends with the exit of all the 'assistants', leaving only Turandot and Calaf, face to face, who must now resolve their problem : to love each other without fear, with the desired impetus.

Calaf leaves and Turandot takes refuge among her four dolls, like a frightened and fearful child, with no more defences.

Act III

Naming the beloved is always a strong question. There is no love without 'naming'. Recall Racine's Phaedra who refuses to name Hippolytus when she confesses her love to her nurse Œnone.

ŒNONE

Hippolytus ? Oh my God !

PHAEDRA

'Tis

you`Have named him.

The name of love is also at stake in Lohengrin, another nameless lover who makes namelessness the condition of love, which is impossible. It is clear that this is a challenge that goes beyond the enigma. It is not just a matter of finding the name, but of knowing it in order to love. Knowing the name of the one one loves is the condition of love.

The answer to the last riddle put to Calaf in Act II is "Turandot", and if naming Turandot means loving her, proposing Turandot as the answer to a riddle that could send you to your death also means verifying the existence of the love that protects from death.

In fact, Calaf's proposal to Turandot to guess her name is also a specular answer to the last riddle. A way to test the power of love.

This is why the third act begins with a distorted vision of space, where Turandot is in her bed on the proscenium, protected by her dolls, and surrounded by this strange carpet of flowers already glimpsed in the other acts, a sort of fairy-tale flowered life path.

The space will then be that of the hall, where everything has been knocked down – chandeliers, chairs, wardrobes – as if the beautiful deadly order of the previous acts had given way to disorder and panic, and that of the proscenium, with all those boxes that are now a useless vision of the princess's final defeat. This first image is a premonitory image of weakness.

The act will unfold between the two spaces, that of the proscenium, which would be that of humanity and the drama of individuals, and that of the hall above, which is that of the State, destroyed and scattered, desperately trying to survive, as shown by the three ministers who try to corrupt Calaf through wealth, power and women (with the irony of Guth giving the 'women' the silhouette of Turandot).

Turandot's arrival marks one of the most famous moments in the act : the scene of Liù's death, brought to the stage with Timur, where the young slave girl takes it upon herself to confess that she knows his name (she loves him and therefore knows his name… as we have said before), in order to divert attention and take upon herself all the suffering and sacrifice of love.

She becomes a sort of opposite of Turandot, with her long black hair (dishevelled) and her torn black dress, next to Turandot with her long white hair and dressed all in white. Liù stands at the proscenium while Turandot sits on the edge of the proscenium in a scene of rather strong violence holding her in a vice between her legs, pulling her hair and trying to cut it off. A vision in which Liù's confirmed love for Calaf materialises in front of Turandot, caught in a trap that tries to eliminate what Liù represents and what she herself is experiencing, unbearable for her.

The rest of the act is built around Turandot's gradual acceptance of love, from the moment she asks Liù what gives her the strength to overcome her pain. When the other replies L’Amore, she descends to the proscenium to listen with great attention (and not incredulity) to Liù's monologue Tanto amore, segreto e inconfessato, which represents for Turandot the worst danger (to which she has obviously already succumbed while still trying to protect herself), for which she calls the executioner to put an end to Liù, but from which she protects herself by resuming in her bed the childish position under the sheets of Act II, protected by the dolls. Liù, animated by a force that frees her from the executioner and the minister, begins Tu che di gel sei cinta in a sort of implicit dialogue between the two women that leaves Turandot contemplative and frightened when Liù takes her own life.

This is followed by a ritual funeral scene (flower petals), a sort of funeral march in which the heroine's corpse is carried, reminiscent of the death of another hero, Siegfried : the dead man who reveals the true. But it is also the moment of the end of Puccini's music, also celebrated by this ritual.

Guth, in a very opportune and intelligent way, brings down the wall separating stage space and proscenium, on one side the space of ritual and the State, and on the other the proscenium, the space of individuals. At the same time, the curtain falls on Puccini's music before, after a brief silence, Alfano's music begins, the duet that Puccini would have wanted to be his own duet from Tristan und Isolde.

In this duet, Turandot, aware that she has been conquered by love, still tries to protect herself from it, stiffening herself in bed with her dolls, but Calaf descends to her level, tears off the protective sheet and gives her the founding kiss Puccini wanted, which the dolls try to prevent with a futile tearing movement. Guth constructs it as a rape, Calaf tears the sheet and the young woman curls up in anticipation of the “rape”.

And then the effect of the kiss, which is the effect of love, penetrates her (staring at her on the stairs) and the duet of love's revelation begins. The turning point of the story, which is the moment of confession (in Phaedra, the confession is the beginning of the end, because in tragedy, spoken words are mortal, but not in comedies such as those by Marivaux. In Marivaux's theatre, the love confession is the moment when all boundaries are lowered, when the expression of truth without false pretences opens up the future. And this is what happens, and Calaf understands it. From the moment Turandot confesses to loving and having loved Calaf as soon as he appeared, nothing prevents him from naming himself, because love implies knowledge of the name. And even if the libretto still reserves a few dilatory moments, everything has been said and there is no longer any doubt in the matter. Resolution.

Then the curtain rises on the room whose floor is this time covered by the flower carpet that covered the staircase in Act I, that marked the entrance to her bedroom in Act II and that hung over the proscenium in Act III, in front of which Liù killed herself and on which, covered by her veil and covering her ears, Turandot received the name of her beloved.

The carpet of flowers (a sort of flowery tapestry, on the whole overly demonstrative) is thus an evocation of this other world, this new world in which everything takes on colours.

The finale is constructed by Claus Guth as a somewhat contrived moment (for which he has been criticised), somewhat rhapsodic and at odds with the refinement of some of the moments that preceded it, but Claus Guth is too clever not to have intended it, especially as this moment (somewhat like Barhaktov's in his direction at Naples, by the way) is not musically one of the most successful in the opera, nor of Alfano's own music.

So he builds up the entrance of the Emperor, still suffering from a cough, and all his people, with the chorus returning to the proscenium this time just as the couple, lying on their flower carpet, are finally experiencing a kind of bucolic intimacy with the dolls collapsed on the proscenium (Turandot no longer needs them), and the scene seems a coitus interruptus. The whole State is present and the bride and groom separate, becoming the 'official' heir couple, the princess and prince sitting on two thrones each wearing a ribbon, as at the end of the fairy tale where the princess marries Prince Charming.

An official photo of the royal family… the Emperor's dynastic goal, mentioned in Act II, has been achieved.

But no, Turandot throws away her royal ribbon and takes off Calaf's, and drags him away, in a finale à la Eva and Walther rejecting the fossilised world of the Meistersinger – a little nonchalance, too, in a musical finale in which only love triumphs over all other considerations. The lightness, the smile, the irony of a Claus Guth who always has surprises in store at the last second.

Musical aspects

Musical Direction

Ever since Madama Butterfly, Puccini's preoccupation with precisely knowing exotic customs and traditions is well known, so as not to misrepresent a world totally foreign to our own.

For Turandot, he wanted to use the Chinese musical tradition not only by expanding the instrumental range, because he was curious to create new sonorities or new music, but also by using well-known Chinese melodies that he could repeat. For example, he took up the popular motif "jasmine flower" (heard in the children's choir, later used as the theme for Turandot) or extracts from the hymn to Confucius, working on the pentatonic scale like Bartok or Debussy.

The second characteristic of this music is marked by the desire to return to a kind of 'Grand Opera', a genre that Puccini had touched upon with La Fanciulla del West, but which did not characterise most of his operas. Moreover, to speak of ‘Grand Opera’ is perhaps a linguistic licence, since the genre was so marked in the mid-19th century, it would perhaps be more appropriate to speak of spectacular opera, and Puccini was very anxious to impress audiences with a grand spectacle, had written very precise captions, and demonstrated a desire for the picturesque that was neither anecdotal nor showy, but rather faithful to a certain image of a China China, already better known in its heyday through photography and cinema. Thus, productions such as "Turandot in the Forbidden City" directed by Zhang Yimou (and conducted by Zubin Mehta) in 1998, beyond their commercial aspect, may correspond to a vision that Puccini had, as did various productions by Zeffirelli, in particular the one for Verona until recently (and indeed directed by Marco Armiliato) and years ago at La Scala with Lorin Maazel.

It is not a question of discussing Guth's intimist approach in the face of the undoubtedly different one Puccini wanted (sic transit…), but of highlighting a musical production with a broad, spectacular and complex scope, to which the great Puccini specialists (Karajan, Mehta, Maazel in particular) left their mark. It was therefore understandable that Franz Welser-Möst, who a few years ago had conducted a fine Fanciulla del West (with Kaufmann and Stemme) at the Vienna State Opera, was eager to complete his vision of Puccini's fresco with Turandot, considered the composer's most complex work (although Fanciulla is not so simple, far from it). With Welser-Möst unable to conduct, Marco Armiliato, well known in Vienna as a quality conductor but more for revivals than new productions, was called in.

Armiliato is no stranger to the score, which he conducts 'all'italiana' as they say, i.e. from memory, and it must be said that the work he did in Vienna was anything but routine, even if it was luxurious. Armiliato succeeded in rendering transparent a complex score, undoubtedly the composer's most elaborate, in which Puccini gave considerable importance to colour, but also to instrumental diversity, with an abundance of percussion and brass instruments, which Armiliato never overpowers, and in which he modulates only in the service of the voices, which as an opera conductor of unquestionable experience he spares, supports, and lets breathe.

The result is one of the finest recent performances of Puccini's masterpiece (in this Theater I have heard Maazel, undoubtedly the greatest Puccinian of the late 20th century, with Marton, Carreras, Ricciarelli and the veteran Waldemar Kmentt's Altoum), accompanied by a particularly committed orchestra. The Wiener Staatsoper Orchestra does not always have the ardour and seriousness one would expect from the orchestra that occasionally turns into the Wiener Philharmoniker on the doorstep of the theatre. But this evening he has the sound, the brilliance, the transparency and above all the desired line : you have to hear how he makes the sounds light and seraphic (the passage of the children's choir is phenomenal), but also how he never presses too hard, making the score airy and subtle, letting you hear all the fine details. Rarely have we heard such a marked difference with the part written by Franco Alfano, not that he plays it less well or with more carelessness, but just, playing it with the same commitment and quality, you can clearly hear the lesser thickness, the less elaborate melodic line, the craftsmanship of the composition and not the genius.

There is clearly a strong understanding between the conductor and his orchestra, which demonstrates the quality and refinement of the work they do together, and which above all shows that when the Vienna pit is big, it has few rivals.

The same can be said for the chorus conducted by Thomas Lang, much favoured in the first act because he sits proscenium opposite the conductor, as in an oratorio, and much less so later, because he is invisible and hidden by a scenic choice that favours intimacy and confrontation between the individual characters. The fact remains that he displays power, precision and real care in his phrasing.

Mention must also be made of the excellence of the Opernschule der Wiener Staatsoper's – Childrens' choir (conducted by Johannes Mertl), whose appearance is one of the scenic and musical highlights of the production.

The voices

The importance of the Viennese repertory system requires a larger troupe than elsewhere, with voices able to replace guest singers unable to perform at short notice, or to take on principal or important roles. So perhaps the so-called supporting roles are more anonymous or less idiomatic than those heard in Naples a few weeks ago, chosen ad hoc, but the fact remains that they all make up a homogeneous and irreproachable ensemble.

Such is the case with Attila Mokus's Mandarin, a role reduced but immediately exposed as he opens the opera (Popolo di Pechino…), with a strong, well-projected voice and smooth phrasing.

Jörg Schneider's Altoum obviously does not have the emotional force of Nicola Martinucci in Naples, but his clear timbre is very decisive and his character of the humanist emperor exhausted by the Kafkaesque horrors caused by his daughter is particularly well rendered.

Similarly, Dan Paul Dumitrescu's Timur, also like the previous member of the troupe, has a warm timbre that suits the character of the old blind man (very different from Alexander Tsymbalyuk's in Naples, more vigorous and youthful); he sings with much humanity, a fine dramatic colour in his voice and excellent projection, both in the first and third acts when Liù dies.

The three ministers, Ping, Pang and Pong, are also particularly well suited to the staging ; in such a mechanistic production, these three characters, often seen as a kind of single machine with three heads, fit perfectly into a production where they are both machines and individuals. The voices (two tenors and a bass) harmonise well with each other, as do the physiques dominated by the bass Martin Hässler, a member of the troupe with a lanky physique, opposed to Hiroshi Amako, a young tenor who is also a member of the troupe and former member of the Studio. We get to know Norbert Ernst better, a character-tenor who was a fine Loge in Castorf's Ring in Bayreuth. As much for their ease on stage as for the harmony of their voices singing together or alternately, with a skilful sense of rhythm and timing, they form a truly flawless trio on stage (they manage to move us and finally appear human at the beginning of Act II) and for their vocal style, irony, colour and accents.

Liù is Kristina Mkhytaryan. She is a rather unusual Liù in this production, as Claus Guth wants to see her more as a figure than a character (she is always accompanied by four Liù who are doubles, like the dolls accompanying Turandot). So her impeccable singing, technically very controlled, with a particularly firm and controlled but somewhat cold breath line, is well suited to this type of character. Of course, Rosa Feola was more vibrant and moving in Naples, but the character was not at all the same. Here she is an officiant, serving Timur and Calaf, and her singing is perfect but distant. Of course, Puccini's music is poignant, but in the context of this performance she remains a restrained Liù (and her black dress and impeccably groomed hairstyle confirm this) at the side of the masters and somewhat distant. And her perfectly fluid and flawless singing confirms this ; she is a perfect Liù, but without the humanity that most often characterises the character. This is clear in the third act, where, dishevelled and lacerated, one might think her singing would break free a little, but it remains as flawless and tidy as her hairstyle was in the previous acts. She did not let loose, which is a pity, because from a strictly technical point of view she has nothing to reproach herself with.

Jonas Kaufmann tackles Calaf for the first time on stage after having recorded it together with Sondra Radvanovsky with Antonio Pappano. His dark-toned tenor voice, which lacks the brilliance of the great Calafs such as Pavarotti or Carreras, or even Martinucci, fits the character envisaged by the staging. He is a love-consumed Calaf who 'suffers' (‘soffro, padre, soffro ! I suffer father, I suffer!' he cries in the first act) and who has nothing luminous about him, and a Calaf who comes from the depths, as the mise-en-scène mimics from the silent prologue by having him emerge from a trapdoor.

Three elements stand out in his performance.

Even today there are more powerful Calafs, more at ease with the demands of the score, but none of today's Calafs can sing first and foremost with this sense of phrasing and accents, with this unique way of saying the text, of marking the words (so clear, so audible). The voice certainly no longer has the youthfulness or luminous energy that we have known in other roles, it is a little duller, but it retains its charm because it is first and foremost expression, first and foremost a play of emission, half-voices, emphases that soften until they are lost and that are unique and moving. His Non piangere Liù is already a miracle of restraint and an expression of deep humanity. His Nessun dorma becomes a meditation and then an inner certainty, an expression of the power of love completely lived and embodied, which makes the moment impressive because he knows how to play even on vocal frailties. No one knows his own possibilities and limitations better than he does and uses them in the exclusive service of expression, such as the different way he modulates vincerò each time.

He gives the character a unique presence thanks to a scenic and vocal charisma that fills the stage : you have to see him in the first act between hesitations, fears and certainties, vague glances and at the same time a spirit of decision ; you have to see his gait, at times hesitant, at times decisive ; you also have to see the sketches of gestures, with the Prince of Persia, the glances towards Timur. In this act in which he is at the centre, he is often fascinating because he is far from the self-confident, domineering Calaf ; he does not defy, he is carried by an inner certainty, as if by faith. And this is fascinating.

Equally fascinating is the more heroic and impersonal singing of Act II, with its incredible moments of sweetness, like the ineffable way he sings to Turandot, paralysed by fear

dimmi il mio nome,

prima dell'alba !

E all'alba morirò ! (tell me my name before dawn ! And at dawn I will die!)

sung with the gentleness and delicacy of a loving caress, a way of singing that belies what she says, because she knows that by pronouncing her name, love will blossom

Finally, on the contrary, he shows total commitment in the third, heroic and heartbreaking role, tackling Liù and then Turandot. Jonas Kaufmann shows us that a great Calaf, that is, a Calaf who sings and lives, who lays bare his humanity and sorrows, completely changes the face of a performance. There are Calafs with much more volume and voice that fail to convey anything. This Calaf conveys so much nuance, so much life, so much strength that he leaves one stunned.

Asmik Grigorian tackled the role ex nihilo for the first time. After debuting Salome and Lady Macbeth during the season, these were other roles in which the singer demonstrated her incredible plasticity, slipping into a character profile from which she drew unprecedented expressive power.

Two weeks earlier, we were faced with an opposite Turandot, Sondra Radvanovsky, also far from the throats of steel to which the role is most often entrusted. But she had the humanity of the Belcanto singer, who sought in her singing technique the humanity so much desired by Puccini. And she was astonishing.

With Asmik Grigorian one does not feel the same culture, but a true creative modernity. Grigorian is an original creator who draws her singing from her inner, expressive strength. When she played Salome in Hamburg, we talked about the broadening of her voice that allowed her to give the right notes and accents to the life she wanted to express. She is one of those artists who are not first and foremost voices, but gestures, movements, attitudes and total commitment that bring body and voice into a new adventure. Asmik Grigorian is carried by a vision, a direction : perhaps she could not have sung in the same way in Vasily Barkhatov's vision in Naples, but here the singing is inseparable from the vision of the character, from its construction.

This Turandot is not a iron-woman (it is impossible to imagine a Nina Stemme or a Birgit Nilsson in this role of a young woman as fragile as a cellulose doll), and here, the fragility of the young woman on her protective bed, with the 'dolls' at her feet, refers through the image to the theme of childhood, of an exposed and anguished childhood that, to protect itself from the world, prefers to apply the law of murder. It is after glimpsing this shadow projected in the first act, this suggestive, almost childlike vision, that we determine our relationship with her singing, with this incredibly confident voice whose limitations, if not fragility, we also perceive, because, like Kaufmann, she manages to convey something of her fragility in her fearsome in this direction through acting alone, through sketchy, contradictory gestures. She manages to convey this interplay between childish ostentation and anguished fragility through her singing, which explodes in despair when she finally refuses to be handed over to the 'unknown prince' who has 'won' her in the guessing game, like a defenceless human toy, like a little girl to her scolding father. She manages to transform In questa reggia, a monologue in which we are used to testing the steel of the voice, into a lyrical monologue, alternating fragility and confidence, playing with colours, with an incredible vocal homogeneity. Rarely has one heard a Turandot like this, singing all the most fearsome notes, taking the character elsewhere, to the land of vibrant maidens, not “throats in armour”, so that the focus is not on vocal performance, but on embodiment.

Her performance in the third act with Liù, whom she almost tries to suffocate with her legs to prevent him from expressing what she herself feels and prevents herself from doing because she is terrified of it, is a spectacle in itself. Her whole changing face expresses these contradictions, which the singing prolongs. In Grigorian's case, the singing stems from such an internalisation of the performance that she imposes an expression, accents that she would not necessarily find if she were not guided by great directors. She is one of those singers who can only express herself fully through a specific reading, built around her character : she is only immense if she is truly 'staged' by directors who perceive her incredible possibilities, who push her out of all her comfort zones and, above all, who create a context for her acting and singing. Quo non ascendat ?[1]

This production was broadcast by the Austrian TV channel ORF2. It should not be difficult to access and I highly recommend it.

A second series of performances is scheduled for this season on 1, 4, 7 and 10 June 2024, conducted by Axel Kober and with Fabio Sartori as Calaf and the rest of the cast unchanged. Visit the website :

https://www.wiener-staatsoper.at/en/season-tickets/detail/event/992495293-turandot/

[1] Adaptation of 'Quo non ascendam', the motto of Fouquet, the Sun King's finance minister, whom the jealous Sun King had arrested and locked up in the fortress of Pinerolo for the rest of his life.