Listen with interest to the conversation between Vladimir Jurowski and Barrie Kosky, interviewed by Christopher Warmuth about this production (in English with English subtitles).

Video of the show on the German-French channel ArteConcert :

https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/114703–001‑A/johann-strauss-la-chauve-souris/

(available until 30 March 2024)

The series of performances are sold out in Munich, demonstrating a relationship with operetta that is still very much alive in Germany (and Austria), whereas elsewhere, in France and Italy, the genre has died, through neglect, misunderstanding and even snobbery. Elsewhere, as in the United Kingdom, the Musical is preferred.

The roots of the operetta can be found in France, in all the musical shows that in the 18th century circumvented the royal privilege that protected the Opera (the Royal Academy of Music), particularly around “La Foire” (the Fair), and which led to the creation in 1764 of the Opéra-Comique, a hybrid genre that mixed music and dialogue and which flourished particularly during the French Revolution and the 19th century.

The operetta (a small opera in the literal sense) was born in the second half of the 19th century and exploded in France, initially with Offenbach's Orphée aux Enfers, before rapidly exporting itself to become a very popular genre in the second half of the 19th century and into the first half of the 20th century throughout Europe : the operetta is a typically European genre. A light, satirical genre in contrast to opera, a serious genre, it developed first in Paris, then in Vienna (as an echo ? as a rival?), and later in Berlin. It was a genre where almost anything was allowed, a moment of liberation.

It was traditional in Germany for the most popular operettas to also be sung by opera singers, and opera houses sometimes hosted operettas, particularly Die Fledermaus, during the festive season, since Die Fledermaus took place on New Year's Eve (the libretto was based on the play "Le Réveillon" ‑New Year’s Eve- by Meilhac and Halévy). The Vienna Opera and many other theatres put on Die Fledermaus for the festive season.

Operetta was a free, wild, slightly mad, often borderline genre that plunged into the musical and theatrical culture of Europe. It was a genre that was rarely exported to the United States, where something different, the Musical, was created, and where operettas imported from Europe were put through the mill of platitude (The White Horse Inn is an example). Operetta is not self-righteous, conformist or moral. Die Fledermaus is a pure example where none of the characters are praiseworthy or what they appear to be.

Most of the most famous operettas, by Offenbach or Strauss, are musically very elaborate works. It should not be forgotten that Offenbach was called "the little Mozart of the Champs Élysées", but both of them also studied Rossinian comedy, the influence of which is largely identifiable in Offenbach, but also in Strauss (see the first act of Fledermaus). We must never forget that Rossini, who lived in Paris, also spent several years in Vienna, and that his musical influence in the first half of the nineteenth century was enormous, everywhere. )

The difficulty in making a success of an operetta like Fledermaus lies first and foremost in holding the whole thing together and guaranteeing a homogeneity between dialogue, song and dance, with such fluidity that you cannot feel any break in the transitions from one to the other, with a kind of guaranteed naturalness that keeps the spectator constantly on the edge of his seat, despite the possibilities for improvisation and the many variations depending on the performers and sometimes the location. This clockwork is what Jurowski and Kosky call, in reference to Wagner, Gesamtkunstwerk, in the sense that not only music, song and staging, but also dialogue and dance must hold together in a tight rhythm reminiscent of a Feydeau-style mechanism. As a result, the absolute success of an operetta production is far less assured than that of an opera. In Munich, the Leander Haußmann production was a crueller failure than many an opera. The sensitivity and fragility of operetta can be due to a singer, a conductor who is not up to the task or a failed staging, and the weak link reflects on the whole product, which is not always the case with opera.

One last detail, which is important given the history of the last two centuries and what we are going through today, the composers of the great operettas were mostly Jewish : Offenbach, Johann Strauß, Oscar Straus, and Berlin composers like Paul Abraham. It is no coincidence that part of the setting for the first act of the Kosky production in Munich that we are reporting on is Judenplatz (Jews' Square) in the historic centre of Vienna. This is obviously deliberate.

The second contextual element is not irrelevant : Die Fledermaus was obviously first performed in Vienna (at the Theater an der Wien), and it is obviously a Viennese operetta in its soul and manifestations, but the last quarter of the twentieth century shifted the focus from Vienna to Munich in the sense that in 1974, for the centenary of the work, Otto Schenk proposed an emblematic production conducted by Carlos Kleiber that has become a kind of signature of the Bayerische Staatsoper, following the example of Rosenkavalier, done with the same team.

Although Otto Schenk staged it again in Vienna in 1979, and it is still in the repertoire (it is currently being performed), the Schenk-Kleiber pairing remains the indelible mark of the Bayerische Staatsoper, which was the benchmark in this field until 1997, the date of the unfortunate production mentioned above.

Carlos Kleiber remains the most emblematic conductor for these two works, in Otto Schenk productions, both of which have Vienna as their context, even if Richard Strauss is Bavarian. In short, “Vienna was no longer in Vienna, it was in Munich”.

This shows what is at stake for the Bayerische Staatsoper in a new production of Fledermaus, featuring the GMD (General Music Director) of the Munich Opera, Vladimir Jurowski, who, although he has already conducted Fledermaus at Glyndebourne, is better known for other repertoires that are sometimes considered stronger.

He is well aware that he needs to continue to make his mark in this theatre, where he is still new. And the call for Barrie Kosky, who is responsible in Berlin for the dazzling revival of Berlin operetta, one of the most astonishing phenomena of the last ten years, is also an essential issue, insofar as Barrie Kosky has never tackled Fledermaus, and Fledermaus is without question the queen of operettas in German-speaking countries.

Failure on such a project would be a huge risk for the current team, given that Fledermaus is so emblematic of the history of Munich's last decades. What's at stake is both the success of the show and its long-term future, where it will no doubt be staged every year for the festive season. It has to be a production that is easy to revive, because in Munich (as in Vienna) a production of Fledermaus lasts for decades. Even Haußmann's lamentable production remained in the repertoire for 25 years, creating only Kleiber-Schenk nostalgia as an unattainable ideal.

So from now on, Otto Schenk's two legendary house productions, Rosenkavalier and Fledermaus, will be replaced by two productions by Barrie Kosky, each conducted by GMD Vladimir Jurowski, the first at the initiative of Nikolaus Bachler, the former general manager of the Bayerische Staatsoper, the second at the initiative of his successor Serge Dorny.

Now that's what we call an official generation change.

Die Fledermaus is an operetta in three acts, built around two very different first acts and a resolute third act that is dramaturgically (almost) botched, or at least very fast. The pivotal point of the work is the madcap finale in the second act, the explosive musical finale of the whole. One of the great originalities of this production is that it gives the third act sufficient scenic weight to allow the only intermission after the second act, i.e. 1 hour 50 minutes of music, and to offer a third act of 50 minutes where the duration should not exceed 30 minutes in the best cases, we'll see how and why.

Let's review the plot.

It is a farce, the "revenge of the Bat", plotted by Dr Falke against his friend Gabriel von Eisenstein, who once ridiculed him in front of the whole of Vienna while dressed as the Bat.

Eisenstein has to go to prison for insulting a civil servant, and before serving his sentence his friend Falke takes him to a ball organised by a wealthy idler, Prince Orlofsky, to which he has invited not only Eisenstein, but also his maid Adele and his wife Rosalinde, disguised as a Hungarian Lady, and to complete the picture the prison governor Frank. Everyone, under false names, gets caught up in the champagne whirl, and Eisenstein thinks he is "seducing" the Hungarian Lady to whom he unwisely leaves his watch…

In the third act they all end up in prison, where Eisenstein is confounded by his wife (who holds up the watch) in front of everyone : this was The Bat's revenge, and everything is resolved in the Champagne.

The first act is a 'domestic' act that takes place in the Eisensteins' home, riddled with various lies. It's a Feydeau-style act in which everyone lies as much as they can between misunderstandings, lovers (almost) in the wardrobe, while keeping their appearance (almost) safe.

The second act is the trap set for Eisenstein, in the middle of Prince Orlofsky's wild evening of polkas, quadrilles, waltzes and champagne. Eisenstein falls for the seduction of the beautiful Hungarian lady, in reality his wife. Under the false name of "Marquis Renard", he befriends Frank, the prison governor who goes by the pseudonym "Chevalier Chagrin".

Everyone meets up again in prison in the third act, which is deliberately more dialogue-driven and less sung, with some expected acting "numbers", such as that of Frosch, the jailer, usually given to a well-known actor who speaks perfect Viennese dialect.

Barrie Kosky's staging respects the highly contrasting characters of the three acts.

The first act is set in the streets of Vienna's old town, with highly recognisable landmarks such as the Kaffee Alt Wien and the Judenplatz (Jews' Square), as we mentioned earlier, which today houses the Vienna Jewish Museum.

Rebecca Ringst's set depicts Viennese facades on trolleys which, by constantly moving, create new playing spaces for the ballet to move around in, but also for the interiors to vary : a huge bed, a living room, a dining room. Only the furniture indicates the interior, all the rest are these very realistic and at the same time dreamlike moving facades, which will strongly accompany the first act and a little less so the second.

The Munich show

The first act could be that of a vaudeville, as has been pointed out, because it is all make-believe, masterfully orchestrated by Barrie Kosky, who knows how to arrange dialogue and song as well as dance without a moment's respite with great naturalness.

The very famous overture takes place with the curtain open, conceived as a nightmare of Gabriel von Eisenstein in his enormous bed dreaming of being assailed by a world of Bats (choreography by Otto Pichler, Kosky's usual partner in Berlin operettas), a ballet of mobile Bats, passing between the facades, dancing in and around the bed, and also obsessing an Eisenstein sitting at a table at Kaffee Alt Wien (boys dressed in Bat masks) who, like a good Viennese, is reading the newspaper (huge headline : SKANDAL EISENSTEIN VERHAFTET (Scandal, Eisenstein thrown in jail). All in all, a foretaste of what is to come.

The first scene opens with Rosalinde in bed (always the bed, obviously an emblem), waking up to the singing of Alfred, her former lover, a tenor whom she resists except when he sings a High C, and who, knowing that the husband has to go to prison for a few days, is getting her bearings for the moment when she will be alone. She pretends to refuse his advances, which do not seem to displease her, when Alfred bursts into the room like a mad tennis player and throws himself into her bed.

Eisenstein then arrives with his lawyer Blind, an incompetent man who has managed to increase the sentence from five days to one week. He complains about this to his wife and, to mark his departure, orders a fine supper which Adele picks up at Sacher's (the place to be for the famous Sachertorte).

Everything is perfectly regulated, entrances, exits, movements : everything is coordinated to a musical rhythm that is sometimes reminiscent of Rossinian ensembles (for example the sillabato in Blind aria :

Rekurrieren, appellieren, reklamieren,

Revidieren, rezipieren, subvertieren,

Devolvieren, insolvieren, protestieren,

Liquidieren, exzerpieren, extorquieren,

Arbitrieren, resummieren, exkulpieren,

Inkulpieren, kalkulieren, konzipieren ...

Directly inspired by Rossini's operas.

In the beginning it's Rosalinde who doesn't seem so clean or honest, Eisenstein seems rather direct and frank, Alfred is in ambush, while Adele the maid also seems a model of cunning.

She has the most musical numbers (more than Rosalinde) in her character as a maid who doesn't take any crap from anyone. She has just received a letter from her sister inviting her to Prince Orlofsky's party. Under the false pretext that her old aunt is seriously ill, she asks to be let out for the evening, with a lot of crying and pretending (a stunning Katharina Konradi), but Rosalinde, who has to be left alone because her husband is in prison, refuses her. Eisenstein has some old clothes brought in for his stay in prison. Everything seems to be in order.

But then Dr Falke arrives and breaks the order by inviting Eisenstein to Prince Orlofsky's party, which is full of women and champagne. Eisenstein can't resist (dancing around the sofa and ending up in morally reprehensible positions) and changes his plans. He puts on his evening clothes, foregoes the fine meal with his wife and heads off to the party.

So Eisenstein isn't too neat either. But then, feeling free as of the evening for her Alfred, whose High C so disturbs her, Rosalinde frees Adele the maid, and finds herself with the dinner set up in front of Alfred, who has unexpectedly returned, dressed in the husband's dressing gown and taking up residence at the dinner table.

The evening could be off to a tender start, but then Frank, the prison governor (an astonishing Martin Winkler), turns up to fetch his prisoner. He finds a gentleman in a dressing gown sitting at a table, and logically mistakes him for Eisenstein. And Alfred, to avoid confusing the lady of his heart, agrees to go to prison to give the impression that he is Eisenstein.

In this first act, we discover a world where no one is who they say they are. Everyone is lying : Adele, Rosalinde, Eisenstein, Alfred. What's more, Alfred is Rosalinde's former lover when she was a singer in another life, so Rosalinde's past is not yet completely closed up and she is going to act out in the second act. And Frank, the prison governor, must also be at the party after locking up Alfred-Eisenstein, to meet the no less false Marquis Renard under his false name of Chevalier Chagrin.

In all these appearances, Plato's cave cannot find its young. And it's Falke who has actually set the whole thing up to confuse Eisenstein.

Kosky directs everything like a breathtaking vaudeville, with not a moment of silence, not a moment of slackening rhythm or tension, and with first-rate singers and actors, skilled at acting, moving, dancing, singing and above all speaking with a rhythm, accents and liveliness that confuse the spectator, so much so that a kind of acting perfection is achieved in the desired genre.

Kosky's ability to manage a sort of boulevard-theatre act, without heaviness or loss of pace, is astonishing. And the lightness of the set and the modularity of the spaces make the whole thing all the livelier to match the airiness of the music. But what is striking, as always, is Barrie Kosky's meticulous theatrical work, the way he manages the movements, which are meticulous but always seem incredibly free and improvised, the management of the groups, the way the characters collide, meet and cross paths, the way they exchange glances, the liveliness with which their conversations are conducted and the casual way they use objects. Nothing escapes his eye, and it is a perfectly oiled mechanism that is offered to the audience here, although the first act is not the most spectacular, but an appetizer in the sense that the elements of the trap that is going to close on Eisenstein are here scrupulously put in place. It is a work of rare perfection, almost more refined than the second act, which is certainly dazzling but perhaps more expected.

As the first two acts are conceived as a whole, the transition between the first and second acts is particularly fluid : all the Vienna sets have to do is move to the sides to free up the central space, which will remain free throughout the act and allow the colourful troupe of Orlofsky's ball to enter.

We find again the sense of spectacle of Kosky's operettas, feathers and sequins where the chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper (now conducted by Christoph Heil) mingles with the dancers, a delirious world where champagne flows freely and everyone lives their gender and sexuality as they wish.

Kosky's idea is obviously to show that the world of operetta is off-limits on every level, an authentically Dionysian world, and in fact it is difficult in the costumes to distinguish the gender of the ball's participants, almost all of whom are sporting silver or glittery golden beards. The dancers, too, as is often the case with Pichler, are indifferently male or female in men's costumes (the Hungarian dancers who accompany the 'Hungarian lady' during her czardas or the feathered dancers who surround Orlofsky), so much so that when Eisenstein kisses one of the Hungarian dancers perched at the top of a set, we cannot be sure whether it is a man or a woman.

This play on gender is dictated by the libretto itself, which makes Prince Orlofsky a transvestite, usually played by a mezzo (Brigitte Fassbaender was a legendary performer in the Schenk production).

Kosky then reverses the tradition, giving Orlofsky to a countertenor, Andrew Watts, respecting the tradition of cross-dressing, but in reverse giving Andrew Watts a beard like Austria's most famous transsexual, Conchita Wurst, (Eurovision 2012). In this way, Orlofsky's party becomes a delirious queer party, during which Falke's trap closes.

As we shall see, many aspects of the play work, including all the characters involved in their 'fake' roles – Rosalinde, Eisenstein, Adele and Frank, who has put on a horrible wig to be the Chevalier Chagrin – but Orlofsky is only partially successful.

Stuck in his Drag Queen dress, Andrew Watts seems a spectacle in himself and doesn't do enough, content to sing (loudly) what he's given, but beyond the costume there's nothing going on around him. In my opinion, it is highly likely that the resource of offbeat gags would have been richer and more delirious with a transvestite mezzo. Or else a more performance-oriented countertenor was needed, of the type Jakub Józef Orliński who was so impressive in Semele this summer at the Prinzregententheater. There is no performance here, apart from the countertenor's singing and Klaus Bruns's deliriously magnificent costumes.

But as we can also be taken in by the game of appearances and being, it is possible that Kosky is showing through Orlofsky not a discrepancy, but a new norm, not burdening him with any zaniness, especially as the character is a kind of depressive who cannot laugh. In any case, the excesses do not come from Orlofsky, but from others. Scenically perhaps a little disappointing, but a disappointment that does not lack logic.

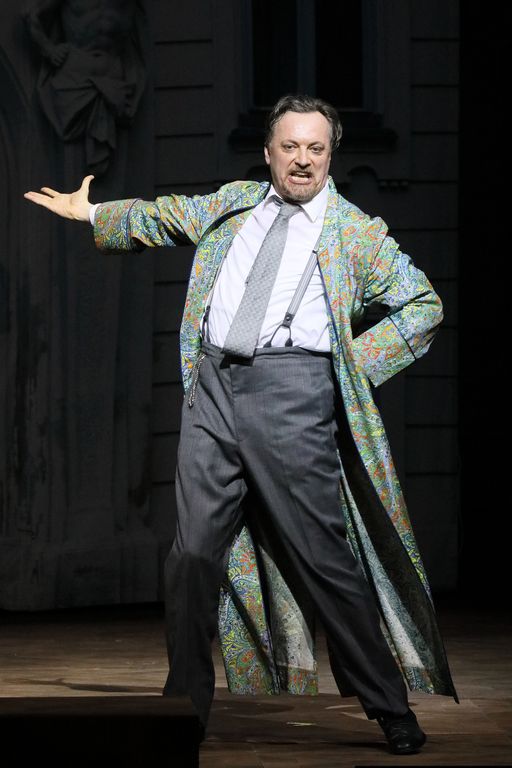

The whole act unfolds with the desired madness, with everyone doing their own thing : Adele (under the false name of Olga) and her sister Ida, Eisenstein as the wild Marquis Renard (the incredible Georg Nigl) and Frank as the deadpan Chevalier Chagrin, both stiff and hilarious (his turn comes in the third act), Rosalinde as the performing Hungarian Lady, who we remember is a former singer who is now retired.

And Pichler has a field day with the choreography, while Kosky, as always, skilfully manages all the movements and sequences, for example the disappearance of the chorus and the crowds as the central characters go about their business, or his reappearance, In Brüderlein, Brüderlein und Schwesterlein, the choir, gathered with the soloists in the proscenium, shows that the moment is in fact one of those suspended moments when the action stops to allow emotion and tenderness to flow between stage, orchestra and audience.

But here again, there is no dead time, all the movements are controlled, especially as this suspended moment precedes the various moments of final madness, starting with Unter Donner und Blitz, the quick polka (usually played instead of the planned music) choreographed by Otto Pichler in which Eisenstein takes part in his final delirium (once again here Georg Nigl is astounding).

The grand operetta finale is provided by a series of illuminated chandeliers that set the stage alight, but Falke's farce and the masks that are about to fall in this society of false pretense are marked by Viennese façades that tear and fall (they were made of paper), revealing the structures of the set, The falling façade is a theatrical "bas les masques/drop the act", while the image of Eisenstein hanging from a swinging chandelier brings to a close the delirious second act in the theatre, reminiscent (somewhat) of the effect of the chandelier in The Phantom of the Opera, which is the essential effect. Kosky thus plays on all registers, that of theatre and appearances, that of spectacular references, and also that of tenderness.

This second act may sometimes seem like déjà vu to anyone who has seen many of Kosky's shows, but it remains a performance of scenic effectiveness, and a huge success in terms of its ability to capture the audience, who are completely gripped by this delirium.

After the intermission, the third act is a completely different kind of appendix, and perhaps the most unexpected moment and therefore in some ways the most successful.

The prison set, a wall of the metal structures that previously supported Vienna's paper façades, as if we were somehow returning to the "real", to the end of appearances. The moment when you pour your champagne.

As we have seen, the act is short and rather weak dramaturgically, and Kosky turns it into a series of performances that have the dual effect of catching the audience off guard and lengthening the show to give this last part a stronger consistency than usual.

After the feathers and sequins comes a staircase wall set, which looks a bit like a world à la Escher and which greatly reduces the stage space where the only furniture is a table and two chairs.

When the curtain rises, it's like a multiplied world, with multiple flights of stairs and six Frosch on each flight, as if multiplied by the effects of alcohol : the third act is in fact the moment when the madness of the ball apparently fades into reality, and six Frosch is a single Frosch multiplied by the illusion of the effects of Champagne.

Of the six Frosch, four are dancers of different sizes, from the tallest to the smallest, who will obviously provide a variety of visual effects. There is one who speaks, Franz Josef Strohmeier (Frosch II), and it is with a performing Frosch (Frosch I) that the act opens : Max Pollak is a tap dancer and a specialist in body percussion.

He performs an authentic Music-Hall number, in a sort of cabaret tradition of tap dancing and body-marked rhythms, ending up tap-dancing Johann Strauss's famous Pizzicato Polka, which the orchestra echoes, sending people in Theater into a frenzy. This is the opening of the act, which replaces Frosch's usual monologue, often performed by a well-known actor in a cabaret number that often features political or social satire. Kosky refuses to serve up the expected moment.

He replaces one 'performance' with another, to which he adds another surprise, the arrival of Frank, the prison governor, practically naked, wearing only pumps and sequined briefs and nipple covers in the style of dancers from feathered revues such as the Folies Bergères or Berlin's Friedrichstadt or Admiral Palast, what remains of the crazy evening and further confirms Kosky's play on genre. Martin Winkler gives the second preliminary performance with an entrance that once again turns the auditorium upside down, looking for his keys in his pants, with his hesitant, wobbly gait (the climb up the stairs and the descent on his buttocks is an irresistible moment).

The whole thing is rounded off by repeated telephone gags : he calls Ida and Olga-Adele-with whom he has befriended during the evening, but it is "Mama" who answers, just as she would later answer Eisenstein. He collapses and falls asleep. This is the end of the beginning, made up of numbers that have lengthened the act and put the audience in a good mood.

This is where the libretto really begins, with a dialogue with Frosch (whom Frank calls Frösche, in the plural as there are six of them).

Entrance of Ida and Olga/Adele, the first visitors to the prison, giving Adele the opportunity for her last aria, one of the act's rare musical numbers Spiel ich die Unschuld vom Lande.

Then Eisenstein enters, also in sequined boxer shorts and feathered headdress, to enter the cell.

This is the moment when all the misunderstandings are cleared up : first Frank introduces himself as the prison governor and not Chevalier Chagrin, and Eisenstein does the same and gives his true identity, but Frank doesn't believe him : he locked Eisenstein in the cell the previous evening when he found him at home, in his dressing gown, bidding a passionate farewell to his wife. Sie nahmen so zärtlichen Abschied, dass ich ganz gerührt wurde (They had such a tender farewell that I was quite moved). Eisenstein's bewilderment is interrupted by the entrance of Blind, the lawyer called in by Alfred who has had enough of his night in prison in someone else's place.

All the possible games about being, appearance and identity follow, a game about who am I ? The real Eisenstein disappears backstage with Blind, leaving Alfred and Rosalinde, who has just arrived, alone. He returns disguised as Blind, and listens to the dialogue between Alfred and Rosalinde (which becomes a trio : Ich stehe voll Zagen, (I am full of apprehension). Eisenstein, who then accuses his wife, is then confused when she presents him with her watch, stolen during the party.

This ending in general confusion is quite clearly reminiscent of a caricature of the finale of Le Nozze di Figaro, where the Count is confounded in front of everyone. All is well that ends well, and while Adele embarks on an artistic career financed by Orlofsky, the Rosalinde/Gabriel couple reunite once again over Champagne.

But it's clear that this is not the end of the story for this elastic couple.

The ending is very swift, with revelations and explanations coming one after the other in the space of a few minutes, with a finale that is less spectacular than that of the second act, but where everything returns to order and the false norm.

But everyone knows that the third act of Fledermaus is usually the weakest and rather rushed, as if for the sake of spectacle, the second act were more than enough.

In fact, Barrie Kosky sows many ideas by refusing to push things too hard. We know his ability to say things in a powerful way (see his Meistersinger in Bayreuth), but also to cover his "messages" with a veil of lightness. Here, he clearly opts for burlesque and lightness, clearly revealing a society that needs to forget itself. Austria in 1874 had become the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867, and its importance had been put into perspective by its defeat by Prussia at Sadowa in 1866 and the very recent birth of the German Empire in 1871. More recently, the stock market crash of May 1873, the prelude to a major European financial crisis, ended a period of economic expansion. A year later, Die Fledermaus served as a consolation, a cure for oblivion.

So Kosky says things (the allusion to the Jews, and to Strauß's Jewish identity, without forgetting that he is Jewish himself), he says the boundaries of gender identity are jumping, he also says the game of appearances (the game of facades being torn apart), but in his brilliant final part of the second act the facades are torn apart while the chandeliers are lit, and as the French poet Baudelaire said, in theatre, the important thing is the chandelier. Kosky has chosen to work on lightness, in the knowledge that Vienna is singing and dancing in a sense on a volcano, and obviously also Munich 2023. What is important here is the need to celebrate and forget. It is no coincidence that the most moving moment of the evening is the hymn to brotherhood Brüderlein, Brüderlein und Schwesterlein… (little brother, little brother and little sister).

But in the case of operetta, the staging may be the most brilliant, but it is nothing without an appropriate musical universe and a cast completely immersed in the project.

It is clearly the collective enterprise that should be highlighted here, and above all Vladimir Jurowski's musical project.

The musical direction

As we have written, Die Fledermaus does not a priori belong to Vladimir Jurowski's usual repertoire, which is more likely to include Die Passagierin (next March in Munich), Prokofiev's War and Peace or Penderecki's Les Diables de Loudun. However, it should not be forgotten that Jurowski has a much wider operatic repertoire, first and foremost Mozart, but also Rossini, whom he successfully conducted in Pesaro in 1997 (Moïse et Pharaon) at the start of his career.

What's more, as Music Director at Glyndebourne, he has already conducted Die Fledermaus.

His opinion is clear, as he states in the interview mentioned at the start of this article : Die Fledermaus is a difficult work to conduct, perhaps more so than an opera.

Not only must the laws of operetta be respected, i.e. the close alternation of dialogue and musical numbers (song or dance) in a fluid continuity that must never break the rhythm or breathing, but in the specific case of Die Fledermaus, the three acts are very different in their organization and their musical demands insofar as the first is a “comedy in music”, The second act, a grand spectacle, alternates large choral numbers, ballets and dialogue forms similar to those in the first act, inserted between the musical numbers. Whereas in the first act, the musical numbers are inserted into the dialogue and the plot in the mode of a comedy in conversational music, in the second act most of the arias are moments of pause, making a spectacle of themselves, the obvious example being Rosalinde's Czardas, but also Orlofsky's arias, and so we are dealing with "numbers" in the almost "Music-Hall" sense of the term, which are so many stops in the action, whereas the arias of the first act helped to move it forward. This is also true of the great choral moments like "Brüderlein" and the entire final scene, which is an accumulation of dance numbers, starting with the quick Polka Unter Donner und Blitz.

But in the operetta tradition, which continues the old tradition of baroque opera, it is also possible to introduce other pieces, to construct musical variations that are not necessarily part of the original version, as in the case of Unter Donner und Blitz, which is now added to most productions.

The musical work also includes incidental music that plays extracts (for string quartet) from Strauss's famous waltzes such as Rosen aus dem Süden (Roses from the South), Künsterleben (Artist's Life) Flühlingstimmen (Voices of Spring) and Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald (Stories from the Viennese Forest), not forgetting the Pizzicato Polka from the third act that accompanies Max Pollak's tap dancing.

These waltzes, which are often heard muted in the background, also sometimes play the role of continuo during the dialogue, to avoid dialogue/music breaks. This is particularly the case in the second act.

As we have seen, the third act is more performative than musical, with a limited number of arias and dominated by dialogue and pantomime : in a way, Kosky takes us back to the atmosphere of a fairground theatre, where forms were accumulated that were intended to "complete" the musical forms, if not to invade them, but also to a more cabaret-style colour, here exploding the operetta form by taking advantage of the dramaturgical weakness of the third act.

Vladimir Jurowski plays on this multiplication of forms, which is obviously complex in its sequencing (the first and second acts follow one another even though they do not at all display the same musical style), but at the same time he defends a score whose orchestration is complex (it is as complex as Mozart, he says) and which obviously draws its style from the pre-existing tradition of opera (opera buffa or otherwise). We have mentioned the obvious Rossinian sources of certain moments in the first act, but also certain aspects of Mozart's Le Nozze di Figaro, which indicates the refinements that a conductor as cultured and precise as Jurowski will try to highlight, alternating rhythms and tempi that are not necessarily usual, but he makes the complexity of the score clearly audible through a reading that is incredibly precise, but just as limpid and transparent, highlighting solo moments in the music stands (the woodwinds, for example), showing musical depth without ever pressing, without ever being heavy-handed or demonstrative. In the Overture, for example, he stuns us with his alternating rhythms, which come together without ever colliding, leading to incredible swirls of sound in the style of Kleiber or Petrenko, the last great conductors to have left their mark on the conducting the piece.

What is striking about Jurowski's work is that it is perfectly in tune with Kosky's project, with which he feels in tune : what happens on stage is extended into the pit, and the pit accompanies measure after measure, word after word, what happens on stage. It is the work of a jeweller, a chiseller, so flexible, so adapted to each form (and we have seen that the moods and forms are radically different in their succession) that is striking. In a moment as calm as Brüderlein und Schwesterlein the orchestra is light, floating, almost chamber-like, only to explode in the entire final section of Act II. And it is completely attached to the text – as with Rossini and with the same meticulous precision – in the sillabato of Blind mentioned above. All this shows a particularly thorough work, never gratuitous in its variations of colours and rhythms, new in certain aspects, traditional in others, a reading completely adapted to the kaleidoscopic staging of Kosky, with whom Jurowski is used to working, in Munich as elsewhere. There is a solidarity between the stage and the pit that is totally exceptional and gives the show all its strength.

None of this would be possible without the contribution of the local forces, the incredible Bayerisches Staatsorchester, in my opinion the most committed and ductile pit orchestra, which sounds here as it rarely does, or as it does on great evenings with great conductors, with perfection of rhythm, perfection of execution, perfection of a unified breath with its conductor.

Obviously the performance of the choir prepared by the new conductor of the house choir, Christoph Heil, must be applauded for its ability to breathe between the music and the stage. The choir is completely committed to the madness intended by Kosky, singing and dancing, but never at a loss for timing, rhythm, tempo or phrasing. It's one of those moments when the stars align to produce a kind of musical perfection, made up of multiple colours in the service of incredible homogeneity.

Finally, let's salute the performance of the dancers, whether they are the Frosch or the Hungarians accompanying the Czardas, the feathered dancers around Orlofsky or the crazy stars of the Polka Unter Donner und Blitz. Composed of members of the Bayerischer Staatsballett, but also of elements used to working in Berlin with Otto Pichler, coming from various horizons including that of the revue, they offer, under the direction of Otto Pichler whose style is so closely linked to Kosky's universe, an explosive, multi-genre universe which obviously contributes totally to the triumph of the finale of the second act.

The stage personalities

Let's be clear, even with a few (minor) weaknesses, the cast is one of the best possible in the genre, because each of the protagonists, especially Adele, Rosalinde, Eisenstein, Frank and Alfred, has to sing, dance, talk – in short, perform and fill the stage. Kosky demands a polymorphous commitment from each of them that is astonishing, even in the world of operetta, which has seen many others in this style.

So let's start with Kevin Conners, the lawyer Blind, one of the pillars of the Bayerische Staatsoper troupe to which he has belonged since 1990. He is a characterful tenor of the highest calibre : we remember, for example, his hallucinatory Mephisto in 2015 in The Fiery Angel on this stage (another Jurowski/Kosky production). His Blind is caricatured to perfection, with that moment of sillabato (Rekurrieren, appellieren, reklamieren…) in the first act, which we have already mentioned several times and in which he is the leading protagonist.

A fine composition too by Miriam Neumaier, a specialist in Musicals and therefore trained to dance and sing as Ida, Adele's sister who accompanies her as her double in the last two acts.

Dr Falke, whose motto could be Jean Cocteau's phrase "Since these mysteries are beyond me, let us pretend to be their organiser", is Markus Brück, always deliberately in the background, never taking part in the surrounding madness (except in the first act to convince Eisenstein), the wise Ringmaster of the whole affair. It falls to him to sing

Brüderlein und Schwesterlein, which Kosky turns into a kind of hymn to brotherhood, the central breath of an otherwise completely mad second act :

Follow my example, glass in hand,

And each one sings, turning to his neighbour :

Brothers, little brothers and little sisters

We all want to be together, sing with me !

Little brothers, little brothers and little sisters,

Let's sing this sweet duet

For all eternity, just like today,

If we think of it tomorrow !

First a kiss, then a you, you, you forever !

The singing is elegant, never caricatured, a sort of mirror image of a deranged Eisenstein, an image of balance and moderation, that of the director of a farce that we won't know if he's the master of or if it's escaped him.

Adele is Katharina Konradi, undoubtedly the triumph of the evening, as this is Adele's most demanding role in terms of singing, but at the same time a hybrid character of cunning chambermaid and shrewd young woman in the second act who seeks to showcase her talents. In each of her postures she is never a caricature, and even her initial tears when her mistress refuses to let her have her evening are an opportunity for a perfectly poised stylistic exercise without ever giving up real poise. It's a miracle of controlled, homogeneous singing, with impeccable phrasing, secure, controlled high notes, breath-holding and a flawless vocal line across the entire spectrum. The voice has broadened and become powerful, and behind this Adele we can already hear a Rosalinde. Every appearance by Katharina Konradi convinces us that she is now one of the most gifted sopranos of her generation, and her triumph here more than confirms that.

Alfred, the tenor-tennisman in this production, is Sean Panikkar, who we saw in Salzburg as Dionysos in the Bassariden in the Warkikowski production, more recently as the excellent Tambourmajor in Simon Stone's production of Wozzeck in Vienna, and as Laertes in Brett Dean's Hamlet in the Munich production. He is a pretty voice, with a lovely timbre, who knows how to play his voice in his quotations from Puccini, Nessun dorma from Turandot, or E lucevan le stelle quoted in the prison, which could not have come at a better time. As a non-native speaker of German, he does himself credit in his delivery of the text, because he has this culture of phrasing that is typical of the American school. He plays the character very well, especially in the first act, although he doesn't quite inhabit him ; you can tell that he doesn't have the immediate ease of some of his partners. But all in all he is an Alfred who is far from being out of place in the ensemble.

Martin Winkler is one of the most kaleidoscopic baritones in existence ; well-versed in the culture of operetta through his former membership of the Vienna Volksoper troupe, we should remember that he was a much-missed meteor in Alberich in the Castorf production of the Ring in Bayreuth (only in 2013). Here he is first and foremost a character before being a voice, a stiff, deadpan character from Act I onwards, but also in Act II, who knows how to use his voice to produce particularly expressive accents. It is in the third act that he brings the auditorium to its knees, appearing in sequined briefs and pumps, constantly maintaining his dignity, also playing with his voice (in the way he mimics the Queen of the Night for Magic Flute), he is first and foremost a character in the theatrical sense, so incredible that one wonders who will be able to replace him on future repertoire evenings in the coming years when the cast inevitably waltzes off (it's a case of saying it).

We mentioned in passing the perhaps mistaken idea of offering the role of Orlofsky to a countertenor. Andrew Watts seemed to us rather stiff in the role, funnier in his costumes than in his singing, which lacked character, accents and colour, and was perhaps delivered too loudly. He played the desired drag-queen character, but nothing more, and above all nothing very funny, less funny in any case than some of the mezzos in the role. He lacks energy, initiative and stage presence. It seems to us that in future revivals a choice will have to be made between a very committed countertenor, an authentic drag queen or an imaginative mezzo. This is the weak link in the cast.

Diana Damrau returns to Fledermaus after a break of more than ten years, where she was a notable Adele, in her first performance as Rosalinde. We admire her playfulness, her colourful delivery, her accents, her freedom of movement and her naturalness ; she is as much at ease in the absolutely irresistible dialogue as in the ensembles and certain musical moments. She has a sense of the stage and a presence that make her a Rosalinde of the highest order.

But it's perhaps a little too late, as the voice has lost its sparkle and volume, and especially its high notes, and in the Czardas of Act II, where she is obviously expected, she misses her final high note, here shouted, because she can no longer hold the note, and the rest, sung with drive and professionalism, lacks a little brilliance : she shines more on stage ease than on her high notes. In a second act where the "numbers" count for most, it's a bit of a shame, but there remains the general composition of the character where she is often astounding in her naturalness, cunning and presence, a true operetta character who gets off successfully but without triumph.

The triumph is Georg Nigl. Known for his exploration of the contemporary repertoire, and having just sung Wozzeck in Munich, he explodes here in a role to which he is committed body and voice. His body is first and foremost a completely mobile face, with bulging eyes that he plays with bewildering expressions, then incredible mobility on stage, lively movements and committed participation in the choreography (particularly in Unter Donner und Blitz, where he gives his all), and the counterpart of Frank/Martin Winkler in the third act, where he appears in sequined boxer shorts and a feathered headdress. He's everywhere, he fills the stage, he's stunning.

But this veteran of Lied and literary texts is an outstanding singer, with his slightly nasal way of pronouncing, letting no word, accent, colour or variation of expression escape, with a strong voice, well poised, homogeneous, so expressive.

It's a unique composition, without doubt the craziest and greatest Eisenstein to be found today. Immense. A benchmark.

Even if Kosky's operetta production is not his most original, it is still the right work in the right place. A welcome production in these times of crisis, war and uncertainty, which breathes fresh and different air, a production of incredible overall quality thanks to a musical ensemble of a particularly enviable standard, led by an inspired Jurowski, with performers committed to the point of madness, who set the audience of the Nationaltheater ablaze, and that's exactly what we expect.

At a deeper level, as they both state in the programme, they are following in the footsteps of a Dionysian tradition in the sense that Dionysus is the God of the theatre, since theatrical performances were organized in his honour in Greece, but he is also the God of Spring, of the rebirth of life, and the God of wine and therefore of excess and madness. Theatre, life and wine would almost be a possible trilogy for Die Fledermaus, not to mention the fact that Greek playwrights were always required to submit three tragedies and a Satyr Play to the competition in honour of Dionysus.

Furthermore, in ancient Greece, comedy, particularly that of Aristophanes, was also largely inspired by current events, so there is no contradiction in making the world of operetta a Dionysian world in every sense of the word and a satirical world that looks at the world from a distance and with irony.

It should be noted that this freedom of tone, which was that of Dionysus, and that of comedy, has not always been the case in more recent times : Aristophanes' Frogs presented by Luca Ronconi at the Syracuse theatre (2002) was censored because it displayed portraits of the Italian politicians of the day.

So to say that Dionysus is the godfather of this production is to say that operetta is not a light or easy genre, but a difficult one that deals lightly with very serious matters.

A trip to Munich is in order or, failing that, a viewing of the video of the show on French-german channel Arte Concert :

https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/114703–001‑A/johann-strauss-la-chauve-souris/

(available until 30 March 2024)