Edward Elgar (1857–1934) is one of those British composers that France thinks it can happily do without. The Dream of Gerontius is performed in Paris once a decade at best : Elgar is above all the composer of Land of Hope and Glory which concludes the last night of the Prom's with a fanfare, and that's that. Pump and Circumstances, to which the lyrics have been adapted to make the aforementioned patriotic song, and the Enigma Variations make up pretty much all that is known about him on the other side of the Channel. Yet there is still much to discover about a composer who eventually opted for silence for the last fifteen years of his life, following the death of his wife.

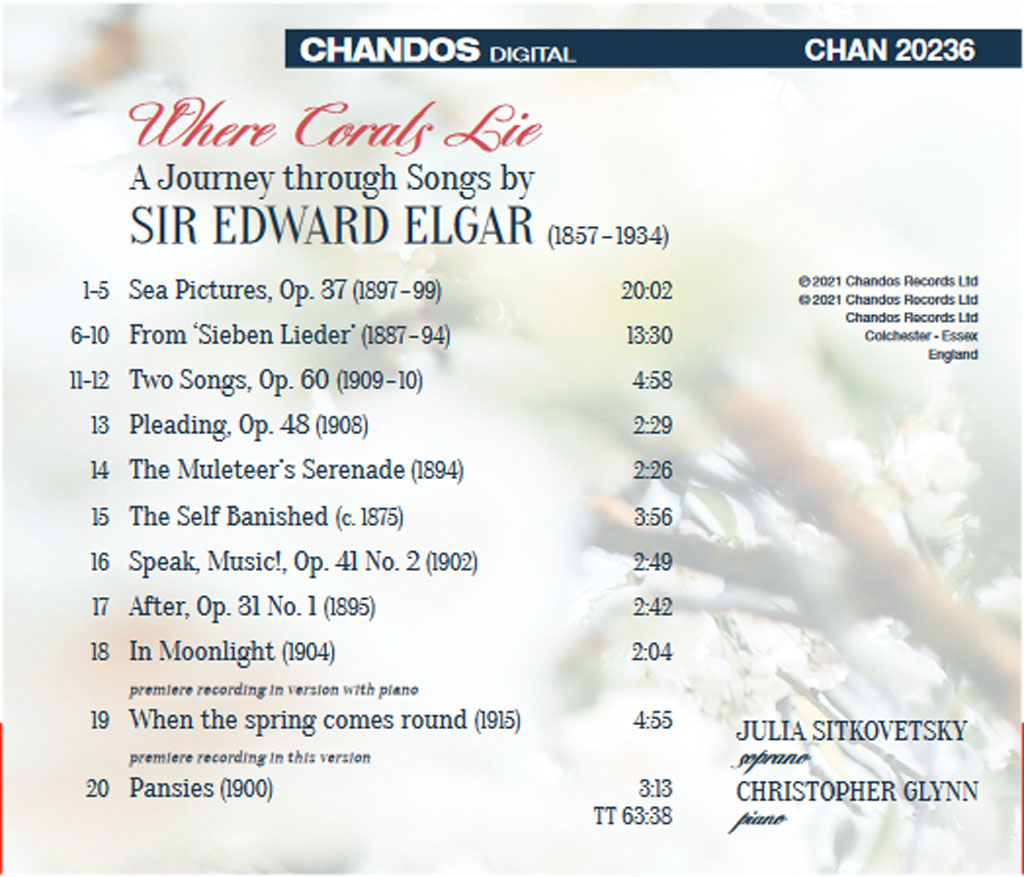

Only recently, Marie-Nicole Lemieux recorded for Erato Elgar’s Sea Pictures, an admirable cycle of melodies lasting some twenty minutes which, half a century before Britten, underline Britain’s insular and therefore maritime dimension. Opulent orchestration and a contralto of Wagnerian proportions, such is the idea that one rightly has of this work. Hence the revelation of the Elgar recital released by Chandos this autumn, entirely devoted to piano songs. Indeed, these five poems were first set to music with an accompaniment conceived for the keyboard alone, and it was the piano version that was premiered in London, a few days after their world premiere (with orchestra) in Norwich in October 1899. The same remarks could be made here as on some recent recordings featuring the vocal-piano version of Maurice Ravel's Shéhérazade : the shimmering palette permitted by the orchestral timbres is of course lost, but one gains an unusual clarity of lines, and the work becomes accessible to less ample voices, while retaining its evocative power and rich harmonies. May the existence of this version with piano contribute to the dissemination of a cycle that deserves to be much more often on the concert programme on the Continent.

At the other end of the programme, another surprise awaits the listener with a famous piece by Elgar, but in an unexpected version : violinists sometimes like to offer as an encore his Salut d'amour, a short, sinuously charming page that Elgar dedicated to his wife in 1888. This sung arrangement was not written by the composer, but by a certain Max Laistner, on a delightfully mawkish poem in praise of pansies.

In between, there's everything to discover, with tunes spanning pretty much the whole of Elgar's career, from 'The Self Banished', the work of a teenager, to 'When the Spring Comes Round' written during the First World War from a French poem by the Belgian poet Emile Cammaerts, to the pages arbitrarily collected and translated into German by a German publisher under the title Sieben Lieder. This is the moment to say a word about the authors chosen for these songs : not all of them are great names of English literature, but we do come across Elizabeth Barrett Browning for "Sabbath Morning at Sea", the third of the five Sea Pictures, Shelley for "In Moonlight", Tennyson for "Queen Mary's Song", one of the aforementioned Seven Lieder, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as an adaptor of the French medieval chronicler Jehan Froissart, and even Cervantes translated into English for the "Song of the muleteer". Alongside these illustrious names, we also find that of Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer's wife, and Edward Elgar himself under the mask of 'Pietro d'Alba', allegedly translating Eastern European folk songs for Two Songs. If you want something done, it is always best to do it yourself, and this pseudo-Syldavian or Pontevedrian folksong is punctuated by the haunting repetition of the name of an imaginary river, the Rustula, recurring at the end of each verse and stanza.

In these Two Songs, but also in many other pages, one notices the muscular accompaniment that Elgar requires from the pianist, very well rendered here by Christopher Glynn, who has already lent his assistance to several discs of vocal music published by British labels (Brahms and Reger on Hyperion, Schubert on Signum Classics). It is also thanks to Christopher Glynn's brilliant playing that the piano version of the Sea Pictures produces the expected effect.

As for Julia Sitkovetsky, she is, as one might guess, the daughter of Dmitri Sitkovetsky. The Russian violinist and conductor left the USSR at the age of 22, in 1977, to settle in New York and then in London ; the soprano's mother is English-speaking and she herself is of American-British nationality, hence her fluency in the language of this disc, her second recital after a Rachmaninov programme recorded for Hyperion and released in 2020. Trained at the Guildhall School, she has become a specialist of The Magic Flute, and this season will be the Queen of the Night in Dresden, Düsseldorf and the Komische Oper in Berlin. This is a far cry from Clara Butt, the British contralto who created the Sea Pictures. Nevertheless, it has to be said that Julia Sitkovetsky is not a mere nightingale. Low notes are naturally not her strong point, but her voice has enough substance to allow her to tackle these pages with their often wide range, to which she lends a beautifully expressive voice, proof that she could undoubtedly play other heroines on stage than Pamina's vindictive mother.