Each new listening confirms that Peter Grimes is undeniably Benjamin Britten's masterpiece, and on can understand why the premiere of this opera in 1945 was enough to launch the career of one who was to be considered the other great British composer after Henry Purcell.

In addition to the dramatic effectiveness of his music, Britten always knew how to rely on solid librettos, systematically drawn from literary works, from Shakespeare to Thomas Mann, Maupassant and Henry James. For Peter Grimes, the adaptation was particularly delicate, since it involved constructing a theatrical action from some of the twenty-four poems that make up The Borough (1810), a collection in which George Crabbe evoked the city of Aldeburgh, located 45 km from Lowestoft where Britten was born. The playwright Montagu Slater, for whom the composer had written some incidental music in the 1930s, fulfilled his mission admirably, and when we know what a shock the discovery of Wozzeck was for Britten, we understand the interest that the story of the sailor Peter Grimes could present for him : Grimes is one of Büchner’s arme Leute, those "poor people" who are prey to the hostility of a whole community, and for whom the love of one woman is not enough to make life bearable (there is even a ball scene in Peter Grimes with a somewhat out of tune piano, a bit like in Alban Berg's opera).

One might therefore be surprised not to see Peter Grimes more often programmed outside the English-speaking sphere. Certainly, there is every reason to rejoice in the popularity of A Midsummer Night's Dream, and we are pleased that Death in Venice or Albert Herring can be a real success outside their native country. After having proposed the Zambello production of Billy Budd four times between 1996 and 2010, the Paris Opera should have hosted the admirable staging presented in Madrid by Deborah Warner, but this project seems to have fallen through. Britten is now only invited to the Opéra Bastille for performances by the Atelier lyrique's young singers : The Rape of Lucretia, seen in 2014, will return this season, and Owen Wingrave was given at the Amphi Bastille in 2016. In its two large halls, on the other hand, the Paris Opera superbly ignores Britten, even though it has a stunning production by Peter Grimes that was only seen in 2001 and 2004 ; Graham Vick masterfully succeeded in transposing the work to our times, a process that helped to make the scenes where the hero is pursued by the villagers' vindictiveness truly terrifying. Once again, we must deplore the lack of curiosity of the Parisian public, who seem to turn their noses up at a work that is too harsh in its content, especially if it is not interpreted by such glamourous singers as Jon Vickers, as was the case in 1981 at the Palais Garnier, or Ben Heppner.

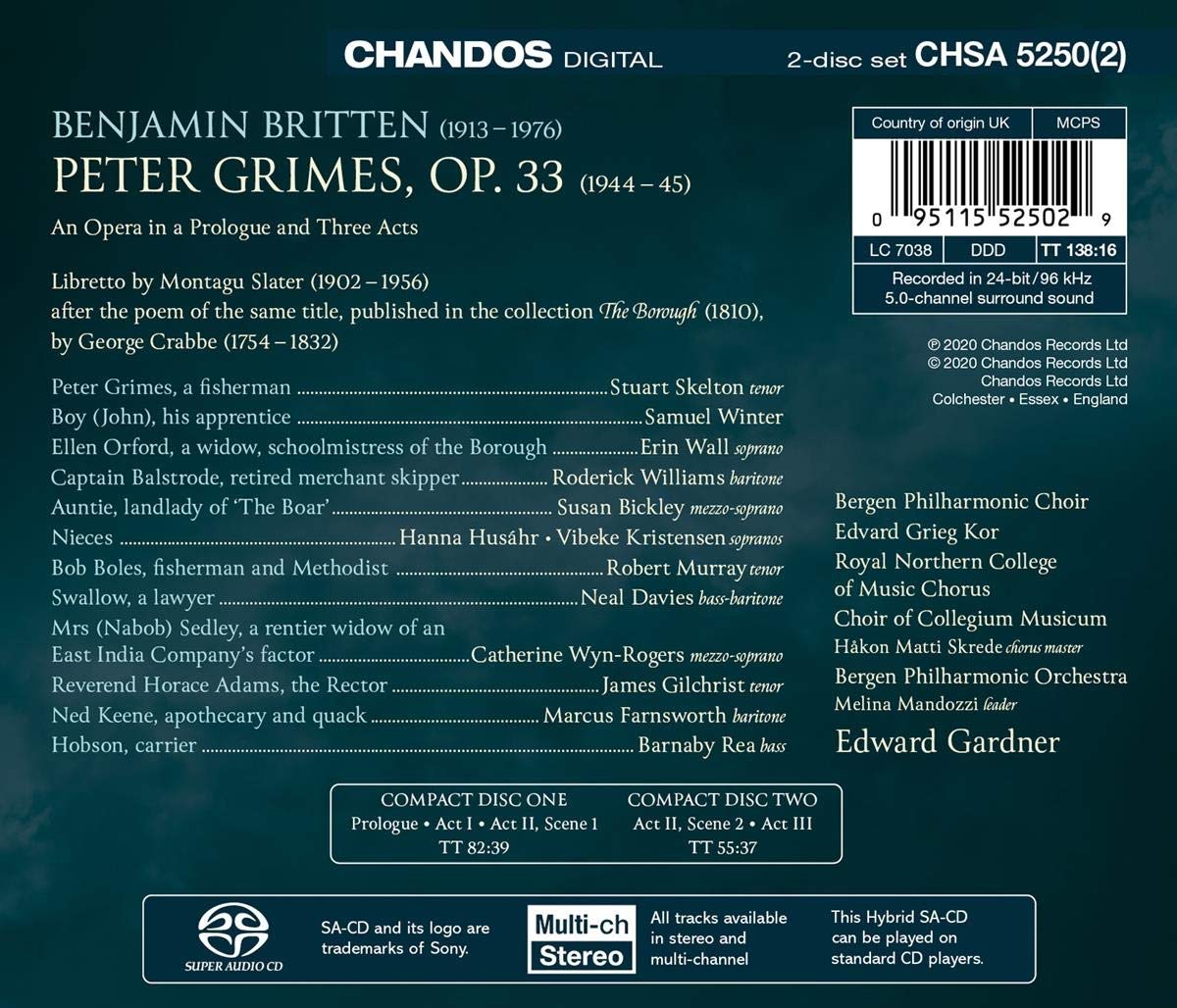

This is all the more frustrating as there exist nowadays singers capable of taking up the gauntlet, and this is proven by the very beautiful recording released this month by Chandos. Although it is a studio version, it nevertheless benefits from the life of the stage and reconstitutes the sound atmosphere of each scene, as one can very well hear it at various moments. In 2017, the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra mounted this semi-stages version of Peter Grimes, which was then presented at the Edinburgh Festival. A few years later, when it was revived in Bergen, Oslo and London last November, the same artistic team was recorded in conditions which allowed to preserve their theatrical commitment.

First of all, one should praise conductor Edward Gardner for the art with which he perfectly conveys all the tension of the work, with moments of irresistible intensity (one cannot imagine a lukewarm version of Peter Grimes). Although recorded separately on the first day, the magnificent orchestral interludes fit seamlessly into the overall vision, and the Bergen orchestra shows that we are dealing with a very high quality ensemble. Britten's score breathes with all its poetry and strength. Bergen's Edvard Grieg Kor is complemented by another local choir, that of the Collegium Musicum, and by students from the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester. The homogeneity achieved by these three ensembles is remarkable, as is the quality of their diction.

Peter Grimes obviously needs a singer whose strong personality can assert itself in the title role. Since it was sung voices as different as those of Peter Pears at the creation and Jon Vickers, one may imagine that practically any gifted tenor could make it his own. With Stuart Skelton, we're at the Vickers end of the spectrum. The Australian tenor has notably sung Samson in Bordeaux, and is regularly Florestan, Otello, Siegmund or Tristan. Thanks to this Wagnerian format, he can offer a multi-faceted Grimes, heroic and roaring in some passages, elegiac in others, reducing or “whitening” his voice when the sailor appears disconnected from the rest of the world as it happens several times. Skelton’s is a genuine incarnation of the part, and he is a true incumbent that we would very much like to see on stage.

The protagonist of Thais published by Chandos last May, the regretted Erin Wall (she prematurely died in October 2020) lends her voice to Ellen Orford. There too, the character has been entrusted to various voices, and sometimes to rather light sopranos, which is perhaps not a very good idea. After creating the role, Joan Cross was to be Lady Billows in Albert Herring in 1947 and the title role of Gloriana in 1953. In other words, a dramatic soprano is clearly needed. Erin Wall has the desired breadth, but her voice does not sound too mature. Her Ellen Orford conveys all the emotions of the heroine (in Crabbe's poems, this melodramatic character has no relation to Grimes, but a female voice had to be given a leading role…).

Far from the media hype, Roderick Williams is today one of the best British baritones, as proven by the many records he has participated in, notably for Naxos and Chandos. His subtle Captain Balstrode fortunately spares us the caricature of the old sea bass.

Around these three main characters, one can hear a real troupe of brilliant artists, down to the smallest roles (James Gilchrist, whose disc of melodies has recently been reviewed, is here the Reverend Adams). One should more particularly note the performance of mezzo Susan Buckley as Auntie, the bar's manageress, as well as that of bass baritone Neal Davies as Swallow. The presence of all these British artists is obviously a token of idiomaticity ; only the two nieces are, one Swedish, the other Norwegian, but Hanna Husáhr studied at the Guildhall School in London, and it is well known that English is not a problem for the inhabitants of Northern Europe.