The title ‘The Maid of Orleans’ sums up Jeanne's legend better than any other. She is first and foremost a “Maid”, and even though the word simply refers to a young girl, without any other connotation, it presupposes virginity (‘she remained a maiden’, as is sometimes said). In any case, virginity is a structural feature of Joan's character, the only woman in a male environment, where, among her companions at the siege of Orléans, there was even Gilles de Rais, who is said to have given rise to the legend of Bluebeard, at a time when women did not fight, did not wear men's clothes, etc., and when any deviation from the social codes of the day could quickly lead to accusations of ‘witchcraft’. Moreover, the fact that her virginity is checked twice shows that this is a central piece of information.

Furthermore, ‘Orléans’ refers to her greatest victory, the one that paved the way for the coronation of Charles VII in Reims.

The title thus refers to her nature as a ‘Maid’ and her historical role. Nature and function, in a way.

However, the word ‘Maid’ alone highlights her uniqueness : women who have remained famous throughout history, since ancient times, have never been characterised in this way… quite the opposite, in fact, starting with Cleopatra or Aspasia, or even Eleanor of Aquitaine, Lucrezia Borgia, etc. Joan of Arc is singular and unique… which is why she continues to fascinate.

The allusion to Cleopatra is no coincidence in this production : when Joan is accused of being a witch and a slut, Tcherniakov (and Elena Zaytseva) dress her as a whore in the same costume that Cleopatra wore at the beginning of his Giulio Cesare in Salzburg last summer… There are no coincidences : the accused woman is always the whore of the moment. And for those who saw the Salzburg production, Jeanne is dressed not as a whore, but as Cleopatra, the royal prostitute, or the queen of whores…

The literature on Joan of Arc is so abundant that it would be futile to refer to it without getting lost in a labyrinth with no breadcrumb trail…

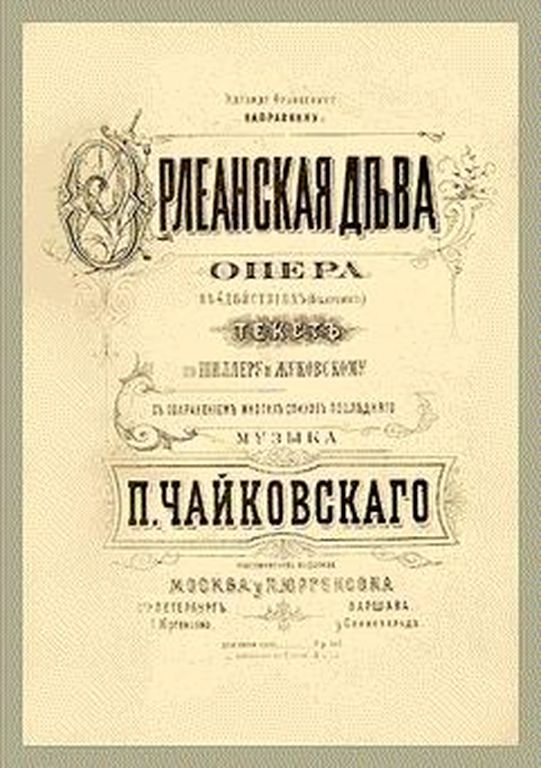

On the other hand, it is interesting to delve into Tchaikovsky's dense libretto, which is based on a simple… and erroneous calculation. After a drama as intimate as Eugene Onegin, Tchaikovsky felt he needed a ‘spectacular’ success, that is, a work that would make a grand spectacle. He therefore immersed himself in a historical subject, one that was fairly well known, and turned it into a kind of Grand Opera, à la Meyerbeer, with numerous different scenes, changes of location, choruses, numerous characters and even ballet (cut from the Amsterdam production). Tchaikovsky, a Francophile who travelled throughout France in the aftermath of the defeat against Prussia, turned to a character who symbolised the homeland and to a typically French genre that had died out in France at that time (the last example of the genre was Verdi's Don Carlos in 1867, or perhaps Gounod's Faust in its revised version with ballet for the Imperial Theatre in 1869, with a libretto by Jules Barbier, author of this Jeanne d'Arc, which inspired Tchaikovsky). Perhaps he thought that such a French subject would then open the doors of the Parisian stage to him, but no Jeanne d'Arc has ever graced the stage in Paris, or anywhere else for that matter. In fact, the history of productions of the work hardly extends beyond the Slavic region (Prague in 1882), and the first complete performances in the USA in 1976 and in London in 1978, on very minor stages, came very late.

Since the 2000s, however, stage and concert productions have been programmed from time to time, such as in Turin in 2002 (Teatro Regio), in Toulouse and at the Philharmonie de Paris in 2017 (Concert version, by the Bolshoi and Tugan Sokhiev), Geneva at the OSR (Dmitri Jurowski) at Victoria Hall also in 2017, and more recently Düsseldorf in 2022 and Saarbrücken in 2023.

Tcherniakov confides that he saw this opera in his youth in Odessa and immediately perceived a kind of secret, a mystery, despite the imperfections of the libretto and the plurality of musical styles that characterise it.

Let us mention the original libretto, as summarised in the programma booklet :

Acte I

Thibaut – Joan’s father – warns everyone about the dangers that await them. War is imminent and, in such uncertain times, Joan must obey her father’s will : she is expected to marry Raymond, to whom she was betrothed as a child. Joan refuses, much to her father’s fury, and he accuses her of being under the influence of sinister forces. Joan confesses that she has a calling that requires a vow of chastity. She feels that it is her duty to stop the bloodshed and put an end to the human suffering. When left alone on stage, Joan convinces herself that now is the time to act. She is overcome by doubts and fears until she hears voices that give her courage and confidence.

Acte II

The war is raging on. In the royal castle, the knight Dunois is attempting to coax King Charles into regaining his pride and sense of responsibility, as the king has been neglecting all his duties. The empty treasury, military defeats and desertions – none of Dunois’ exhortations make any impression, though ; the king seeks distraction in the arms of his lover Agnès Sorel. When Dunois hears that the dispirited monarch is planning to flee, he threatens to resign his post. At that critical moment, salvation comes in the form of a miraculous young maiden, a bringer of victory. The archbishop is prepared to confirm the miracle officially. Joan appears before the assembled crowd. She is convinced that if she can help the king, she will be helping everyone. By order of King Charles, Joan is granted extraordinary powers.

Acte III

Joan meets the enemy knight Lionel. They start fighting, but suddenly Joan hesitates : she cannot take her eyes off Lionel’s face. She finds herself incapable of delivering the final blow and urges him to flee. Confused and moved, Lionel asks her to follow him. Joan loses her self-confidence and is overcome by her emotions. She feels that she has broken her sacred vow.

Charles celebrates his coronation and honours Joan publicly as his heroine. Suddenly, her father Thibaut steps out of the shadows. He accuses his daughter of consorting with the forces of Hell and demands that she proves her innocence publicly. Dunois draws his sword to defend her, yet Joan remains silent, convinced that she cannot counter these accusations. Everyone turns their back on her. The archbishop too poses the same question : is she guilty ? No answer. Everybody deserts her. Lionel offers her his protection, but Joan rejects him.

Acte IV

Joan is alone, consumed by despair and longing. Doubting her calling and rejected by all, she waits and calls out desperately for Lionel. When he appears, she hears the voices : she has broken her vows and allowed earthly love into her heart.

Joan is sentenced to death. In the presence of a large crowd, she is prepared for her execution. Then she hears the voices again ; this time, they are bringing forgiveness.

From these pluralities, Tcherniakov constructs a singularity that corresponds to the character of Jeanne as seen by Tchaikovsky, while at the same time attempting to concentrate the action around the only act for which we have truly precise evidence : the trial.

Thus, the work unfolds in a single setting, a courtroom, with a cage of the type seen in Russian trials, where the accused are placed. The gigantic wooden set, created by workshops in Amsterdam, which overcame major challenges (the roof alone weighs ten tonnes), is installed on a revolving stage that turns a quarter turn at a time, allowing the viewpoint to change each time without changing the location, with interior-exterior effects that begin as soon as the audience enters the theatre, where the building is seen from the outside, with large windows allowing you to glimpse the interior.

The idea is quite simple : to use the plot to tell the story of Joan's trial, with flashbacks, but also projections of the future (as in the first images, which show the verdict being read), interspersed with moments from the “present”, with quick cues at each moment to help the audience follow along.

Instead of getting lost in the twists and turns of the plot, Jeanne's point of view is constantly emphasised, with Gleb Filshtinsky's lighting effects (sometimes chilling, like guillotine blades) separating the present from the past, the assistants from the protagonists : the chorus, which plays an essential role in this work, is therefore constantly present at the trial, acting as a kind of ‘audience’, but according to Jeanne's visions, it can represent the peasants of Domrémy, the courtiers of Charles VII's court, the soldiers, etc. It is a choir in the ancient sense of the term, a tragic choir that comments on each moment, a support, an enemy, a simple spectator ; it is also, in a way, a metaphor for the audience in the theatre watching the story of this strange and mysterious figure.

Everything is therefore superimposed, without ever creating confusion or problems of legibility, but Tcherniakov's genius composes a perpetual game of hide-and-seek with history, current events, and collective and individual destinies. Through the figure of Jeanne, we see the mechanisms of triumph and downfall, or how one goes from the Capitol to the Tarpeian Rock, that is, to the stake.

Solitude in a cage

It is impossible to progress act by act, as the performance is a constant back and forth between past and present, and the scenes are only represented through the prism of Jeanne's memories and narrative, while others are hallucinatory, thus also showing Jeanne's mental confusion and psychological disorders.

But there is one fixed point : the dock, a cage typical of Russian trials, which awakens our intellect, but which is also a “psychological” cage, obviously symbolising Jeanne's isolation in her psyche, in a system that others cannot penetrate. Today we would say ‘in her bubble’, but her bubble here is a cage, that is to say, a prison. Jeanne is a prisoner in a trial, and at the same time a prisoner of her own mind, of the system she has imposed on herself : virginity, heavenly voices, calls from the beyond, guilt. She is cut off from the world, cut off from others and from those closest to her, notably her father, whose intervention in this opera sends her to the stake. Jeanne's isolation is such that she does not even have the support of her family, from whom she has also cut herself off by saying ‘no’ to Raymond.

As for the others, Charles VII, Agnès Sorel, and the archbishop, they are authorities who will use Joan as much as possible and then quickly turn away from her : saints always end up being a nuisance to politicians.

So this cage is a physical and mental cage, separating Joan from others forever. Others cannot understand her and she has nothing to do with them, as if she were of another order. This cage is the physical translation of what Tcherniakov says in the programme interview : ‘Joan was a troublemaker, someone who didn't fit into a neat compartment. I don't want to use her as a symbol of some modern movement or ideology — she has been misused for that purpose too often in the past.’ … ‘What fascinated me was not so much the real, historical Joan as Tchaikovsky's Joan — his own personal interpretation. My task was to listen to that Joan.’

Shortly afterwards, he restores coherence to the character, whom he associates with Tchaikovsky's line of female characters, from Tatiana in Eugene Onegin to Lisa in The Queen of Spades : ‘They are all visionaries who cause trouble in the world around them, which is ultimately their downfall.’ He continues : ‘Each of them breaks with their old life and what is considered “appropriate” at a decisive moment. It is an act of courage, as well as one of self-destruction. Their rebellion is both magnificent and tragic, but the bravery they demonstrate remains breathtaking.’ ‘

Later, he adds, ’At the heart of the production are her trial and conviction. We see her there alone, beset upon, already stigmatised. The scenes with other characters show them as witnesses, either in her favour or against her. The trial is constantly interrupted by flashbacks, memories, hallucinations and visions. What we see is her inner world." (…)

In a way, the cage in which she is locked up is her only truth ; everything that revolves around the cage is merely projections of a mind in which memories, unfulfilled desires and other visions merge. This opera, as Tcherniakov sees it, is first and foremost one of solitude, rather than one of singularity. To make her a singular figure would already be to take a step towards others and their behaviour : ‘she is not like us’, ‘she is not like everyone else’ and therefore not to excuse, but to explain the stigmatisation.

In the first act, she undoubtedly commits the worst of all breaches : she breaks with her father, rejecting the destiny he promises her and the husband he has chosen for her, Raymond. Disobeying one's father is the most serious offence in the eyes of patriarchal society. And she becomes suspect in the eyes of her own father when she predicts the defeat of the English by invoking heavenly voices. This initial “sin” in the name of the patriarchal code cannot go unpunished, and in the drama of the work, it is her father who intervenes in the midst of the triumph to cast doubt on her purity. Joan's ‘principal’ crime : saying no to her father, which is a crime according to a ‘human’ code. There is something of Antigone (in Jean Anouilh's famous play) in Joan, as she is portrayed here, who says no to Creon… she condemns herself to death in the world of men from the outset…

This loneliness cuts her off physically from everyone else, but while Tcherniakov declares that her loneliness makes her the most interesting of all the characters, it is nevertheless the gaze of others and their behaviour that lead to the drama. Tcherniakov's gaze must therefore be merciless on everyone, on the one hand, in order to reinforce the wall of incomprehension that separates Jeanne from the others, but at the same time, Jeanne goes through each moment, triumph, downfall and condemnation, with a kind of equanimity and almost indifference. It is a meticulous work on movements, looks and gestures of incredible precision, as always with Tcherniakov.

Jeanne does not seek honours or recognition, but only claims to be fulfilling a mission. Others have no influence on her, as she follows her own path, regardless of their character, reactions or moods. This Jeanne is not a militant, but a small being who follows her own determined path, oblivious to her surroundings but guided by her own logic : her cage protects her, in a way, from the turmoil of the world.

As we have seen, her father is the first ‘opponent’ in this story and he will remain, in a way, the only one, or rather the one who will ultimately justify the attitude of the others, their reversal or their indifference. In Tchaikovsky's story, the English are mentioned, but they remain distant and we never see them. It is the court of Charles VII that is much more clearly identified in the libretto, and which in the third act turns against Joan at the intervention of her father, in a manner as brutal as it is unexpected. The libretto itself rejects anecdote here, and the fourth act leaves her alone with herself and her own ruptures, even her betrayals or what she believes to be her betrayals : there is no opera without a love story.

Verdi's Giovanna d'Arco depicted the unlikely love affair between Joan and King Charles, while The Maid of Orleans falls in love with an enemy knight, Lionel, whom she spares and who seeks to save her in the final act, at least (in this production) in a hallucinatory vision of Joan.

We have mentioned Anouilh's Antigone, and in our analysis we will delve deeper into the world of the French playwright, as he is one of the hidden keys to understanding this production. Anouilh's Antigone says no to everyone, including Haemon, the man she loves and to whom she is betrothed ; she is uncompromising. She is described as ‘a skinny, swarthy, withdrawn young girl whom no one in the family took seriously’ and who will ‘stand alone against the world’… In this description of Antigone, taken from the famous prologue to Anouilh's play, we can clearly see something of Jeanne.

But at one point, Jeanne meets the gaze of Lionel, the enemy knight, and says ‘yes’ to him. She spares him at the very moment of her own victory, at the height of her glory.

At the height of her glory, she falls.

There is always a moment when one risks succumbing, and Jeanne is both strength and weakness. She resisted her father, who wanted her to marry Raymond, and she also resisted Dunois, the knight who is in love with her, who tries to bring Charles VII back to the right path and who will try to defend her when everyone rises up against her, but she cannot resist Lionel. Their eyes met in battle when she held him at the point of her sword, just as Isolde's eyes met Tristan's when he was wounded and in her hands under the name of Tantris. Tchaikovsky knew his Wagner well…

She took a vow of chastity, as the first act indicates, but falling in love means giving up that vow in her mind, letting her mind be occupied with something other than her divine mission. Even though she has not ‘sinned’, she considers herself a sinner.

After being stripped naked and violently examined on a gynaecological chair by soldiers (in the story, her virginity was checked twice, but by midwives, during her meeting with Charles VII and during her trial), Tcherniakov stages (in the form of Joan's hallucination) the meeting between Lionel and Joan in the fourth act in a very delicate manner, in contrast to the soldiers' violence and the erotic violence : Lionel helps her to get dressed again, that is to say, he restores her honour and her status as a human being. This is also a deeply humane perspective, which places the relationship between Lionel and Joan on the level of chivalry, of the ‘courtly’ novel. In a way, it is what Joan dreams of…

It is one of the most beautiful moments in the opera because the music expresses the power of love and emotion, and the gestures express respect for codes and, in a way, what we would today call ‘consent’.

Tcherniakov does not shy away from the fires of love, but he does shy away from the acts themselves : it is Jeanne's multitude of inner flames that speak here. Separated from others, disowned by her father, abandoned by those she has helped, she has found (fantastically) a kindred spirit in Lionel. At the same time, she imagines herself abandoned by her heavenly voices insofar as she has ‘chosen’ earthly love. At the height of her abandonment, alone on earth, she met a human gaze and, for a moment, she chose the human over the heavenly.

But she chose the human at a time when her mission on earth, the one that made her stand up against her father, seemed to everyone to have been accomplished : Orleans was saved and the king was crowned in Reims. The world no longer needed a saviour like Joan : she could even become a somewhat cumbersome nuisance for politicians. Kings do not like to remember being saved by others, they do not like to be asked ‘who made you king?’. And Joan, from a decorated and honoured heroine, becomes a burden. Moreover, giving her a medal is a reward for a job well done and, in a way, brings the adventure to a close : medals are given when everything is over.

There are also men around her who love her and seek to help her, there are these traces of humanity : Raymond in the first act, then Dunois, who try to protect her (because they love her…), Lionel, who also loves her, wants to take her away and save her from punishment, but he is killed by the soldiers : Jeanne returns to her structural solitude, which cuts her off from the world and the earth. She no longer even has the heavenly voices (or believes she no longer has them) to support her. Sola, perduta, abbandonata, as Puccini's Manon Lescaut sings, as if, paradoxically, Jeanne's heavenly mission and Manon's dissolute and frivolous life led to the same fate of an abandoned woman.

The others

The defendant's cage is, as we have seen, a symbol with several meanings : it is the dock in the Russian judicial tradition, but it is also the cage in which the character is locked up, a mental cage that cuts her off from the world. The way the cage is shown from various angles makes us, the viewers, voyeurs of a solitary suffering from all angles, but the voyeur remains outside, he is simply a gaze. A gaze cut off by the bars, and therefore a gaze that is already disturbed, diverted, indirect. Even if innocent, or as we say today, presumed innocent, the accused in the dock remains an accused, remains the object of judgement. For his part, the accused looks at the world and others with the same obstacle of the grille separating him : a physical grille, or a mental grille, which could be a kind of grille for interpreting the world. Jeanne's mission is to ‘put an end to the carnage’, as the summary of the work puts it, and to ‘human suffering’. It is a solitary, almost abstract mission, a contract between herself and her heavenly voices. She is thus of a different order that is not the order of the world : her relationship with others is therefore secondary in a way, the end justifies the means and the means are ‘others’, but the end remains of an order that others can neither understand nor share.

Hence the even more pronounced sense of the barrier that separates her from the world and from others. Even when she is outside the barrier, outside the box, she carries it within her. Her mission goes beyond the facts themselves, beyond the individual battles, beyond Orleans, the king and the coronation, and the games of humans do not affect her, cannot affect her, until she meets Lionel's gaze, which brings her back down to earth, to suffering, to contradiction and guilt : her silence in the face of her father's accusations and demands for answers in the third act is an acceptance of what she is accused of : her irresistible love for Lionel is worth breaking her contract, at least in her logic and in her mind.

The games of humans are first and foremost the anathemas of her father, which are premonitory from the first act onwards, who thinks she has a rendezvous in the forest with evil forces, to which Jeanne responds in the finale with her grand farewell aria, (‘Простите вы, холмы, поля родные’/ Forgive me, hills, native fields). From the first act onwards, the others are the peasants fleeing the war, perhaps the only moment when Joan appears as a tribune leading the crowd, as a leader : she leads the peasants in a hymn, ‘Give us peace again, give us victory over our enemy!’ (‘Дай снова мир, дай нам победу над нашим врагом!’).

It is in the second act that ‘the others’ take on a more pronounced meaning, since we are at court. The scenes are constructed as paradoxes : the enemy is approaching, the French are defeated, but at court, Charles VII sings and dances with his mistress Agnès Sorel.

Voltaire, in his satirical poem ‘La Pucelle d'Orléans’ (The Maid of Orleans), which was placed in Hell, opened his first canto with the charms of Agnès Sorel :

Le bon roi Charle, au printemps de ses jours,

Au temps de Pâque, en la cité de Tours,

A certain bal (ce prince aimait la danse)

Avait trouvé, pour le bien de la France,

Une beauté nommée Agnès Sorel.

Jamais l'Amour ne forma rien de tel.

(The good King Charles, in the springtime of his life,

At Easter time, in the city of Tours,

At a certain ball (this prince loved dancing)

Had found, for the good of France,

A beauty named Agnès Sorel.

Never had Love created anything like her.)

Voltaire, La Pucelle d'Orléans, Canto I (Chant I)

Tcherniakov shows both the king's frivolity through a kind of frenzied dance between the couple, in which Agnès Sorel, dressed as an authoritarian matron (the extraordinary Nadezhda Pavlova), tries to protect the king from anything that might bring him back to his duties, treating him like a child while Charles VII does everything he can to escape reality. Tcherniakov constructs a relationship between a woman-mother who guides a man-child with genuine tenderness, while also establishing a distance without ever overdoing it, with her contradictions and gestures that show her inability to take on any responsibility : the couple moves from frenzied dancing to prostration and melancholy. Tcherniakov depicts them in their own world, also separated from that of others, leaving it up to the audience to judge this ‘power’…

The entourage is limited to Chevalier Dunois, the ‘reasonable’ one who tries to bring the king back to his duties (He bears a ‘wine stain’ à la Gorbachev, which is not insignificant : a worm in the fruit of a regime in dire straits), particularly because rumours of defeat and the probable catastrophe to come darken the whole scene at one point, leaving the court panicked and defeated. It is a vision of power ‘above ground’, which no longer has any initiative and which, like children after a big mistake, no longer knows how to get out of the situation.

The character of Charles VII is very well drawn by Tcherniakov, between his childishness, his refusal to face reality, his crises of despair and his prostration : it is this changeable mood that gives Agnès Sorel her stabilising and maternal role : the couple is beautifully evoked here in a relationship that is established – we see an old couple, not young, headstrong and scatterbrained – and a toxic relationship since it acts as a screen for the king's profession. As an aside : how could Joan place her trust in such a figure ? She does not judge the individual, but the King as a figure of power ; it is he whom she leads to Reims, regardless of the individual, which is not Jeanne's concern. This is the famous double postulation of the royal body, the individual body and the mystical body (see Louis Marin's famous essay, ‘Portrait of the King’)[1].

The arrival of the archbishop, another ‘authority’, is a dramatic turn of events or ‘Deus ex machina’. It is the arrival of the Church as an authority, essential in the story of Joan. Until now, religion had been evoked, with heavenly voices in the first act, but one could also think of superstition. Here, it is the power of the ecclesiastical institution that recounts Joan's victory near Orléans and her imminent arrival : initially, the Church supports Joan (or uses her). This is when the famous scene of Joan's recognition of King Charles VII takes place, which all children in France have learnt about in the ‘national narrative’. Charles VII, to verify the young girl's ‘supernatural’ reputation, hides among the courtiers, and Dunois takes his place.

This scene is perfectly staged, with Dunois ‘playing the king’ in front of Joan, who is not fooled. She goes directly to the king to speak to him. This gesture affirms the character of royalty, which emanates from God, and Joan recognises in the king the mystical person from whom it emanates, and which does not emanate from Dunois. Even if he is mediocre and frivolous, Charles VII remains the king and is recognisable as such.

This recognition evokes the idea mentioned above that kings are of a different nature than men, that their power comes from God, and that Joan is in direct contact with the Divine. There is nothing anecdotal about the episode of the King's recognition : by recognising him, Joan affirms that the King is of a different order, she recognises his ‘mystical body’ and thus justifies the need for coronation. So, first we had a child-king playing with his mistress-mother in the sandpit, with melancholic music and wild dancing, and it all ends with the recognition of a King whose specific power emanates from God, to whom Jeanne reveals two of the three prayers he addressed to God the night before, which were prayers for self-destruction and withdrawal from power, that is, the prayer to be stripped of his “mystical body”. But Jeanne's presence changes everything.

The others also appear in the third act in all their versatility : it is the third act that shifts from the Capitol (scene of triumph) to the Tarpeian Rock, scene of accusation, by the same people.

All these scenes unfold, as we have said, with a set that moves a quarter turn, changing perspectives and a time that is just as elastic : The clock in the courtroom moves forward and backward according to the scenes and their place in the evocation of Jeanne's adventure, to show that chronology no longer matters in Jeanne's memories ; time moves, but so does space (fans, etc.). Jeanne's inner world is a Phlegraean Field…

But the third act begins with the encounter with Lionel.

In Schiller's play, Lionel is English. But Tchaikovsky does not show the English, who are never seen, since the battles are evoked and recounted, but never shown. In Tchaikovsky's work, Lionel is a Burgundian knight, and therefore an enemy insofar as the Duke of Burgundy is the enemy of the King of France and an ally of the English… but as a Burgundian, he comes from French soil, and so by “betraying” Burgundy for Jeanne, he returns to the “legitimate” royal fold… Honour is saved. And in Tcherniakov's work, Lionel is undoubtedly a jailer, but that is anecdotal.

We have already mentioned this delightful and fateful encounter, which brings Jeanne back down to earth by introducing her to love, but at the same time, in her mind, takes her away from Heaven. By giving in to love, she abdicates her mission.

Dramatically, this is the point that will turn the story around and cause Joan not to respond to her father's accusations of witchcraft and treason. For the first time, Joan is troubled and unworthy of her mission and of bearing the sword : ‘Ah, why did I trade my staff for a warrior's sword, and why was I charmed by you, mysterious oak tree?’ (‘Ах, зачем за меч воинственный я свой посох отдала и тобою, дуб таинственный, очарована была?’).

It is Jeanne, trapped in her own logic and her own cage, who will bring about her own downfall.

After the triumphant scene in which the king is crowned and everything seems to have stabilised, amid the joy and fanfare of trumpets (visible on stage), Father Thibaut (Gabor Bretz) appears. He had disappeared in the second act and, like a Verdi hero who appears to remind us of misfortune in the midst of happiness (think of Silva in Ernani), shatters the happiness. This is the moment of the downfall.

The power of the scene lies in the fact that it concentrates both triumph and downfall, with the same characters going from friends to enemies in a matter of minutes.

In Tchaikovsky's mind, it was a great scene of triumph, in front of Reims Cathedral, with colourful costumes and sumptuous choirs.

In Tcherniakov's mind, the scene draws its strength from the courtroom setting and from the same characters who will pass indifferently from triumph to defeat.

It is when Charles VII addresses Joan : ‘Transform yourself, show us your luminous and immortal face’ (‘Преобразись, дай видеть нам твой светлый, бессмертный вид’) that her father Thibaut steps out of the audience and exclaims : "Do you think, he says to the king, that the power of heaven has saved you ? You are mistaken, sire ! People, you are blinded, you are saved by the art of hell!‘ (’Ты думаешь, — обращается он к королю, — могущество небес тебя спасло ? Ты, государь, обманут ! Народ, ты ослеплен, вы спасены искусством адовым!").

As Joan is convinced that she has failed in her mission because of her earthly love for Lionel, she remains silent and does not defend herself. This is her downfall.

Court judgements paint you as either white or black. Joan has accomplished her mission in the eyes of the king and all the authorities : they are all there, the soldiers, the people, the knights, the king, Agnes, the Archbishop, her father, but also Dunois, Raymond, Lionel, Joan's three helpers who are powerless. Even Heaven, with its thunderclaps, accuses Joan… But is it Heaven, or is it Joan in her delirium and anguish who believes she is being rejected ? Is it an inner thunder ? This is what Tcherniakov is trying to show : a distraught soul who, accused, adored, rejected, loved, no longer knows where her real place is, except in this eternal cage.

Joan is both a victim of others and a victim of herself, a victim of her own decline in her own eyes, a decline she cannot refuse : unlike Schiller's Joan, who abandons Lionel, Joan first rejects him and then takes refuge (mentally) with him in the adversity that follows and at the bottom of her personal abyss.

Once again, loneliness is evident here, but so is the fickleness of others, of assistants, and of the world. By staging the phases of this trial, the memories, the projections, the hallucinations, Tcherniakov turns Jeanne's soul into a field of ruins, and he stages the same crowd that applauds and curses, the same soldiers who protect, celebrate and insult. She becomes the supreme whore (in the same clothes as Cleopatra in Giulio Cesare in Salzburg, as already mentioned), she is undressed, humiliated, put in her cage on a gynaecological chair and examined by men with particular violence – it is an image of rape. This is the beginning of the fourth act, which is the definitive confirmation of decline and the end.

It is also the scene we mentioned above of the duet between Lionel and Jeanne, who delicately helps her to get dressed again and thus restores her honour : this is the moment of the hallucinatory love duet ("O wonderful sweet dream ! ‘/’О, чудный сладкий сон!"), which ends with the arrival of the soldiers who take Lionel away and shoot him. Once again, loneliness, this time definitive, without the help of dreams.

She is sentenced to death. Unlike in Schiller's version, in Tchaikovsky's she dies burned at the stake in Rouen, but in Tcherniakov's, when the verdict is announced, the curtain falls and we learn that the courthouse is on fire : the curtain rises again and she has immolated herself in the flames crackling before us.

Another key, more political

This ending immediately raises questions : a fiery end is consistent with history, but not this sacrificial end, where she takes the world with her, an end worthy of a heroine of freedom, like the student Jan Palach in Prague in 1969, or the monk Hòa thượng Thích Quảng Đức in Saigon in 1963, or Mohammed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2011. Whatever the motives, self-immolation is a political act, still quite common today, and gives this final vision a meaning closer to the reality of the contemporary world.

This is the third element of Tcherniakov's staging, which is undoubtedly the least obvious to Western eyes, but the most obvious to Russian eyes : by suggesting an ending that borders on terrorism, a terrorism born of despair and isolation, but also of the incomprehension of others and of the world, Tcherniakov offers an even more topical and political interpretation.

The trial of Joan of Arc is obviously a political trial, a set-up, insofar as the whole debate surrounding Joan was about whether she was a saint or a cursed woman, and the character of the father in the opera is the bearer of this. The figure of the father who more or less sends his daughter to the stake is strong enough to show that in certain circumstances and under certain regimes, there are no longer any family or filial ties that hold : Tchaikovsky already tells us this.

By focusing the work on the trial, by making the audience spectators of Joan's trial, he also makes them witnesses to a conspiracy. One thinks, of course, of Iranian trials, or of all the more or less rigged trials that take place in totalitarian states, where justice is subject to orders.

It was clear that Joan in the hands of the English would end badly, and that the trial, however procedural (i.e. with all the appearances of a ‘fair’ trial) it might be, would end with the stake.

And we naturally think of Russian trials under Stalin… and under Putin.

It is then that Russians who follow theatre in Russia know that a talented director, Evgenia Berkovich, considered one of the promising figures of the young Russian theatre scene, staged Jean Anouilh's L'Alouette (The Lark) (1953), which describes the trial of Joan of Arc, as her final year project in 2012, turning it into a metaphor for Russian trials.

One need only read the Wikipedia entry for The Lark, which is rarely performed today, to understand Tcherniakov's intentions here.

Essentially a play within a play, Joan reenacts key moments of her life throughout a trial. The play presents the trial, condemnation, and execution of Joan, but has an unusual ending. Remembering the important events in her life throughout her questioning, Joan is subsequently condemned to death. However, Cauchon realizes, just as Joan is burning at the stake, that in her judges' hurry to condemn her, they have not allowed her to re-live the coronation of Charles VII of France. The fire is therefore extinguished, and Joan is given a reprieve. The actual end of the "story" is left in question, but Cauchon proclaims it a victory for Joan.

The intentions of the staging are clear : Tcherniakov, like Anouilh, is proceeding in the same way in his staging, as a kind of homage…

To Anouilh ? No, but to Evgenia Berkovitch, because Evgenia Berkovitch has now been sentenced to six years in prison for condoning terrorism.

Of Jewish origin, from a family of intellectuals, with a great-grandfather executed during Stalin's purges, a grandmother who was a writer and a grandfather who was unable to become a film director because of his Jewish origins, Evgenia Berkovitch inherited her passion for theatre from her grandfather, while her mother is a human rights activist and her father a poet.

It was both her public stance against the war in Ukraine and an award-winning play (‘Finist’) featuring the wives of jihadists who had emigrated to Syria that triggered the repressive machinery. She was arrested along with her colleague and work partner Svetlana Petriïtchouk, and this arrest sparked a wave of protests, including a petition with more than 16,000 signatures. They were sentenced to six years in prison in 2024 and are currently serving their sentences.

Evguenia Berkovitch (© AFP)The photo of Evgenia Berkovich in the dock, dressed in her prison uniform, leaves no doubt about the superimposition effect achieved by Tcherniakov. On the one hand, he denounces the trial of Joan of Arc as an example of an unjust and destructive trial, and on the other hand, he reminds the Russian audience (many of whom are in the theatre) of a case that is very much on the minds of the Russian intellectual world (whether in exile or not).

This evocation is overlaid with another message, that of the indomitable power of theatre, of the tradition of the artist as a ‘fire thief’, to use Rimbaud's expression, in the face of the world and its cowardice or fickleness. We then understand perfectly that the chorus, the audience at the trial, is a metaphor for populations manipulated by the powerful, a kind of society that is losing its soul, framed by ‘institutions’ that manipulate them to retain power, religion, kings (or oligarchs), soldiers, and informers (including fathers…): the picture becomes a picture of a society eaten away from within, facing which the artist stands alone, the sole bearer of humanist and spiritual values.

Thus the powerful become a representation of an oligarchic society that is only interested in maintaining its power over the rest of the population, who are ready to follow the highest bidder (Jeanne in the first and second acts, the oligarchs in the third and fourth). This brings to mind Stefan Herheim's 2011 production of Eugene Onegin (conducted by the legendary Mariss Jansons) on the same stage in Amsterdam, where Tatiana, having renounced her ideals, ended up marrying a (already) oligarch, Gremin. Even though she is convinced that she has betrayed herself, Jeanne, on the contrary, goes all the way and dies forgiven, her mission accomplished.

Contrary to what he claims in his interview (one should not always believe what is said in interviews, just as one should not always believe what is said in prefaces), where he says he rejects the political use that has been made of Jeanne, the figure of Jeanne is used here, just as he uses (without saying so) Anouilh, the playwright, superimposing Berkovitch, the director, and more generally celebrating the strength of the theatrical genre, which is still so vibrant in Russia, as shown by the profusion of Russian artists present on the Western stage.

The history of theatre in Russia in the 20th century is a contradictory model : with Stanislavski, one of the founders of modern directing and acting, who remains a reference today, and with Meyerhold, the brilliant creator and victim of the purges, who ended up being killed in Stalin's prisons. Theatre is a tool of liberation and therefore a danger, but also a tool of ‘ideological propaganda’. We remember the affair of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, a huge success blocked by Stalin in the name of socialist realism, which almost cost Shostakovich his life. The play did not reappear in the USSR until the 1960s, under the title Katerina Ismaïlova, and even then it was expurgated. But the 1960s were years of liberation, when going to the theatre became a substitute for civic life and when (almost everywhere in the East, in Poland and in the GDR) directors emerged who presented themselves as new interpreters of the world and the repertoire. This was the case in the USSR with Yuri Lyubimov, director of the Taganka Theatre in Moscow, who also had a “few minor” problems with the regime in power.

All this is a heavy past and a liability, but theatre remains a privileged means of artistic expression, and the liberalisation after 1989 allowed artists to blossom and explode onto the Russian stage, the Vassilievs, the Dodins (we remember his ‘Gaudeamus’) and, more recently, a figure such as Tcherniakov, whose first productions emerged in the early 2000s.

But Putin's regime tightened its grip in 2012, and even more so after the start of the war in Ukraine, which it justified as an ‘ideological war’, also requiring ideological revisionism at home. Thus, Kirill Serebrennikov, of whom Berkovitch is a disciple (there are no coincidences), was placed under house arrest and eventually went into exile, but the Berkovitch trial was the first trial to indict an artist and theatre director since the Soviet era. In this sense, beyond Berkovitch, it is the trial itself that is the ‘character’ in this story, which is why it is the focus and backdrop of this ‘Joan of Arc’.

It should be noted, however, that Tcherniakov does not make Berkovitch into a modern-day Joan of Arc, something she herself strongly rejects : ‘I'm just a girl, I want to go home. I don't want to be on a banner ! Don't make me into Joan of Arc!’ she declared during her trial. What is presented here is the mechanics of the trial, the trial as a theatrical mechanism. Moreover, according to those present at her trial, Berkovitch put the witnesses and the prosecution in difficulty and turned it into a kind of theatrical performance, focusing in turn on one person or another.

This is what Tcherniakov proposes in his work, a theatrical staging of the trial, reminding us in the subtext that the great Stalinist trials were conceived as spectacular events to ‘stage’ the confessions of the accused in order to edify or frighten the crowds.

Moreover, like others (including Tcherniakov), and unlike others (such as Serebrennikov), Berkovitch chose not to go into exile and to remain in Russia, with all the risks that entailed.

Through the image of Joan of Arc's trial, and beyond the heroine herself, we see the continuation of Dmitri Tcherniakov's discourse, which takes the form of a painful vision of the consequences of war (implicitly, in Ukraine, but not only there), seen from various angles (War and Peace in Munich, Iphigénie en Aulide/Tauride in Aix, Ariadne auf Naxos in Hamburg, Giulio Cesare in Salzburg). This ‘Maid of Orléans’ is here the fragile but stubborn Jeanne, caught in the nets of wars as ideological necessities, who rises up to preserve the world, beyond individuals and powers. From a certain point of view, it is also Berkovitch, who emphasises her fragility and her refusal to be a standard-bearer, but wants to be the grain of sand that disrupts the machinery of intolerance and totalitarianism. A small grain of sand in her cage, whose mere presence destroys the entire system : it is enough for her to be there.

Hence the final fire, which can also be seen as a metaphorical and purifying fire. The small grain of sand will become large.

Tcherniakov tells us that this grain of sand is, in fact, theatre, a permanent disruptive element in societies that are becoming fossilised.

And overall, navigating between the said and the unsaid, speaking through the project but never through words, this production is highly political, to be read entirely between the lines, affirming theatre as what it has always been : the standard-bearer of freedom to speak, think, believe and create, but at the same time a gathering place for a society in all its diversity, which comes to listen to the “Word” rather than the empty words of some political discourse. A society without theatre is a society that dies, and the presence of all the spectators is irrefutable proof of life… And by signing this Maid of Orléans as an immense claim to individual freedom, but also to social mission (Jeanne's metaphorical ‘mission’), he turns it into a production of extraordinary power, transposing Jeanne's rescue of France into the rescue of humanity by the theatre, here and elsewhere. It took courage.

Music and singing

Such a powerful show brings together Russian artists in exile who have settled in Germany or elsewhere in Europe, as well as invited Slavic artists (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Moldovan) and others from different backgrounds. No doubt great care has been taken to ensure that the cast and crew are as diverse as possible, so as not to give rise to any accusations of bias. And it is interesting to compare, just a few days apart, the Hamburg premiere of Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila, an opera that almost founded Russian national opera, conducted by Azim Karimov, and Valentin Uryupin's The Maid of Orleans, both of whom have been in exile since the war in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine is a wound that has affected all Russian artists and intellectuals, regardless of their position and situation, and the large number of Russians in both theatres shows that beyond walls and borders, beyond political statements, this intellectual world is very much present and is rebuilding itself whenever necessary… It is rebuilding itself because we must recognise the vitality of this Russian musical and theatrical world : as I have often pointed out, Russian singers are spreading out across the major stages and without them, we would undoubtedly have some difficulty in casting many roles. But if we consider the conductors, whether they are called Karimov, Uryupin, or also Jurowski (Dmitri and Vladimir), Kirill Petrenko or Vassily Petrenko, Tugan Sokhiev or Teodor Currentzis (who, although Greek, owes everything to Russia), many are at the top of their game.

And let's not forget the directors : Tcherniakov, of course, Serebrennikov, Titov, Kouliabine, etc.

Regardless of their individual situations, the Russian government has no interest in undermining this situation, which, on the whole, serves it well. Sometimes against their will, all these exceptional artists demonstrate an intellectual vitality that owes nothing to Putin, but which he can ride on. It's all profit without having to spend a penny on propaganda. In any case, they show that beyond political situations, there is a lively intellectual circulation that advances art and also humanity. The fact that this show brings together so many nationalities and so many different situations is a wonderful example of ‘resistance’, in a way, to diktats wherever they come fromNazism in its time had broken an incredible musical dynamic (degenerate art, etc.) that had emerged in the 1920s. Putin cannot prevent anything, and that is fortunate.

The fact remains that the wound caused by the war in Ukraine is still there, raw, still festering and unhealed, but it is still productive : art needs drama, not what Sainte-Beuve called ‘happy flowers’.

This is how we should view Tchaikovsky's music and Valentin Uryupin's interpretation, which we heard in another rare Tchaikovsky work in Frankfurt, ‘The Enchantress’ (Чародейка).

We concluded our review of him with the following words : "The result is a performance that leaves a lasting impression and gives this little-known score an unprecedented, overwhelming depth and presence, leaving the listener completely stunned and enthusiastic. ‘The music of ’The Enchantress‘ has a more consistent colour than that of ’The Maid of Orleans", where we note Tchaikovsky's desire to immerse himself in musical atmospheres that do not belong to his horizon. He was a keen observer of non-Russian music and a connoisseur of Italian and French repertoires (incidentally, he hated Verdi's Giovanna d'Arco). He wrote about a French subject (albeit filtered through Schiller) after having just written Eugene Onegin, an intimate opera based on one of Pushkin's great masterpieces. Moreover, he had little faith in the success of his Onegin and invested heavily in his Maid of Orleans, and we know how that turned out.

Firstly, he did not have Pushkin to support the rather weak libretto, which he wrote himself, and he wanted to stage a historical epic that would be spectacular. This required more grandiose musical scenes, with choirs and sumptuous orchestration, brass instruments galore (and even a ‘banda’ on stage).

Tchaikovsky always took care to ensure the accuracy of the colours he gave to his work and his music, as he did, for example, in the pastoral interlude of The Queen of Spades, modelled on 18th-century music. Thus, for the minstrels' chorus at the beginning of the second act, Tchaikovsky used a genuine old French air from his Album for Children (1878), ‘Old French Song’ (Старинная французская песенка).

In fact, rather intimate music (Jeanne's arias) alternates with more extroverted music, and while Jeanne's music and arias are often particularly moving, other scenes are musically forgettable.

It is therefore necessary to navigate between several styles, and there is a surprising heterogeneity, but Valentin Uryupin's particularly precise conducting attempts to give it unity by emphasising the exceptional choral moments (the second part of the first act, in particular) and Jeanne's arias, accompanied with warmth and genuine delicacy, never covering the voices, in a contrasting style that does not shy away from certain vulgarities, but also highlights the orchestration. The bucolic landscape of the opening scenes in Domrémy is sketched out (by the flutes) to better contrast with the tension and drama that follow. The end of Jeanne's aria is accompanied by particularly well-placed interventions from the woodwinds and harps, before a finale in which we find Tchaikovsky's typical accents in a particularly successful hymn-like finale.

The conducting is lively (especially in the second act, which is particularly interesting, playing on the irony of the court's vision and evoking a kind of medieval tableau, with Uryupin taking care to avoid pomposity) and supports the choruses without overwhelming them, constantly striving to highlight the colours and the differences in musical texture, particularly in the way certain woodwind solos are left isolated.

Thus, the beginning of Act II, a sort of pompous symphonic introduction à la Meyerbeer with fanfares and trumpets that could be bombastic, retains a certain fluidity, even if the contrast with the Minstrel's song (here the planned tenor choir is reduced to a single voice, which gives an even more marked melancholic colour after the bombastic beginning) which sets the ‘medieval’ mood, then opens one of the most scenically and musically regulated scenes : Dunois' accompaniment is particularly tense and rhythmic. Uryupin clearly seeks to give priority to the theatre, and the music in the pit is often discreet, allowing the voices to flourish.

The orchestra (Nederlands Philharmonisch) sounds at its best, and this is all the more evident as Uryupin's conducting is clear and allows the sections to stand out distinctly. The orchestra is a true protagonist here, as demonstrated by the impressive introduction to the third act, which is supposed to represent the battle and precedes the (fatal) encounter between Lionel and Jeanne, through its rhythm, contrasts and ductility.

Despite the weaker moments of uneven music, Uryupin ensures consistency and overall colour, maintaining a line that also allows the more profound moments to flourish : in a way, he hides nothing of the weaknesses, knows how to use certain scenes clearly modelled on French or Italian styles, but also shows the depth of this music, its strength, its most sublime and theatrical moments. In fact, he presents it with genuine honesty, offering an impressive, touching fresco, which is sometimes a little repetitive without ever becoming tiresome. This is the second time I have heard him conduct Tchaikovsky, and he is just as convincing as he was in Frankfurt : he defends this music with incredible courage and great precision and mastery, but also with real commitment and genuine love.

As always, the Dutch National opera Chorus, prepared by Edward Ananian-Cooper, is particularly flexible, adaptable and accustomed to daring staging : here it is compact and truly impressive. I have considered it one of the best opera choirs in Europe for a very long time (Moses und Aron, Peter Stein, Pierre Boulez in the 1990s) and it never disappoints. In the “choreography” devised by Tcherniakov, where it is almost always present, front or sideways, moving or stationary, it remains remarkable and is an indispensable protagonist of the production. In a traditional production, it would be decorative, but in this production, it is as indispensable as the audience at any trial and thus becomes an actor in Jeanne's destiny, just like “the others”…

Serving the production is a particularly well-matched cast, where, as mentioned above, care has been taken to bring together artists from all backgrounds, chosen for their vocal colour and stage presence, making room for the local Studio (the beautiful voice of the Angel of Eva Rae Martinez) but also giving an artist from the choir (tenor Tigran Matynian) the solo part of the minstrel at the beginning of the second act, a very exposed aria in which he proves himself truly remarkable.

The ensemble composes a vocal palette of particularly welcome colours and timbres.

Bass Patrick Guetti had greatly impressed us in Die Frau ohne Schatten (Prod. Kratzer) at the Deutsche Oper Berlin (where he is a member of the company), where he sang a Geisterbote full of relief. Here he sings three small roles, Bertrand, Lauret and a warrior, with just as much vocal presence. Definitely an artist to watch.

We are familiar too with Oleksiy Palchykov, a member of the Hamburg troupe, whom we heard in Narraboth (Salomé, prod. Tcherniakov), but also at the Komische Oper in Rodolfo in La Bohème and in Pâris in La Belle Hélène. The Ukrainian tenor's voice is solid, fairly even, and particularly well suited here to the role of Raymond, promised to Jeanne, rejected, but always seeking to appease his father's anger. He is a figure of tenderness and solicitude, and his voice here sounds particularly appropriate, accurate and sweet.

The father, Thibaut d'Arc, is played by bass-baritone Gabor Bretz, whose voice always has great power and a certain brutality or fixity that can sometimes be criticised. But here, in the role of the inflexible father, it is the right voice, without nuance, the one that seems unshakeable, powerful, the voice of guilt and condemnation, carved in stone.

It is almost a luxury to give John Relyea the role of the Archbishop, which he obviously performs with the necessary authority and power. He represents the church that will condemn Joan after welcoming her, and he gives the character the political ‘duplicity’ necessary for characters without moral foundations.

Andrey Zhilikhovski is a favourite singer of Dmitri Tcherniakov, and in War and Peace in Munich he was an unforgettable Prince Andrej Bolkonski. Here he is Lionel, the Burgundian soldier in love with Joan who distracts her from her mission : we rediscover the velvety warmth of his tone, his beautiful projection and the desperate energy of the performer. He has the colour of passionate and tragic lovers, as always moving, as always exceptional.

Another exceptional singer is Vladislav Sulimsky, a baritone who was an unforgettable Macbeth in Salzburg and an immense Mazeppa with Kirill Petrenko in Baden-Baden. His powerful, expressive voice always leaves room for the performer, and he is a Dunois of unquestionable authority, with an uncommon strength that fills the stage in the second act with his reproaches to King Charles VII. His strength, expressiveness, the colour he gives to the words, and the weight of his words echo the tenor ‘lightness’ of Charles VII (Allan Clayton). A remarkable performance, and one to be expected from such an artist.

Nadezhda Pavlova is well known as Teodor Currentzis' favourite soprano, who always amazes with her sense of composition and the diversity of the roles she tackles. We still remember her much-discussed and unusual, but fascinating Zerbinetta in Hamburg in Tcherniakov's Ariadne auf Naxos… Here she returns to a consoling role, this time for King Charles VII, but in a different tone, with her maternal, more mature demeanour, protecting a childish Charles VII and seeking to cut him off from others, a figure of lightness who contrasts with Jeanne, of course, including vocally. Her voice is always clear, luminous and energetic, with confident, well-controlled high notes and incredible stage presence. She creates a truly compelling character. Exceptional in every pose and particularly in the ensembles…

Charles VII, the child king or rather the king child, is Allan Clayton, a tenor discovered a few years ago in Candide directed by Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper, where we had already noticed his stage presence, his commitment and his vocal expressiveness in a repertoire that was idiomatic to him, in the English language. We saw him again later, still at the Komische Oper and still with Kosky, in Mahagonny, where he was a moving Jim Mahoney, about whom we wrote : ‘The prize goes to Allan Clayton's magnificent Jim Mahoney, with his heroic, beautifully controlled voice, (…) at once violent and tender, naive and commanding…’

Clayton is a tenor for major compositional roles (Brett Dean's Hamlet, which he sang in Munich, also comes to mind), and we note first and foremost his constant attention to phrasing, his clarity of expression and his incredible stage presence in all styles. Here, he is initially a child king, a ‘player’, but without the ‘physicality of the role’, as Tcherniakov intended, a powerful carefree figure who apparently does not look at others, but who succeeds through his interpretation in making it clear that he is aware of his situation and that his carefree attitude is a way of hiding his despair. It is always a balancing act that never descends into caricature. Very strong. Very impressive.

And then, last but not least, Elena Stikhina is Jeanne.

I have no affinity with this singer when she attempts to sing the Italian repertoire, Aida or Tosca, and is barely tolerable as Alice Ford. Her phrasing is improbable and her technique approximate. In short, best avoided.

I therefore feel all the more free to write here that Tcherniakov has built with her a character with a phenomenal stage presence, who exudes, simply physically, incredible emotion (she is dressed in the style of Evguenia Berkovitch, with short hair, in a kind of modest perm). She knows how to be unique, and the fact that she also sings in her own language gives her performance an unusual emotional power. She is an incredibly well-crafted character who is at once reserved and shy, withdrawn, yet also displays tremendous energy : she radiates on stage to such an extent that it will be difficult to detach her from this character, who for me constitutes an authentic creation, a milestone in her career. So, if we want to nitpick, we could point out a few excesses of vibrato, but all the singing is in the service of interpretation and expression, which must be both ‘committed’ and ‘distanced’. The voice is powerful, full-bodied, with a wide range, and the high notes are sustained and broad. One cannot help but be carried away by a performance that at times borders on the sublime.

No need to conclude… go to the Dutch National Opera website, then rush to any train station or airport, there are still a few seats left and it runs until 2 December 2025.

In addition, the show will be available in early 2026 on Arte Concert. Date not yet specified.

[1]Louis Marin, Portrait of the King : Louis XIV (Language, Discourse, Society) – Hardcover, Palgrave MAcmillan, 1988