He is the captain of an immense ship carrying 230,000 passengers, making 220 stopovers, with an impressive crew of collaborators, on a six-week luxury cruise... This flagship is the Salzburg Festival.

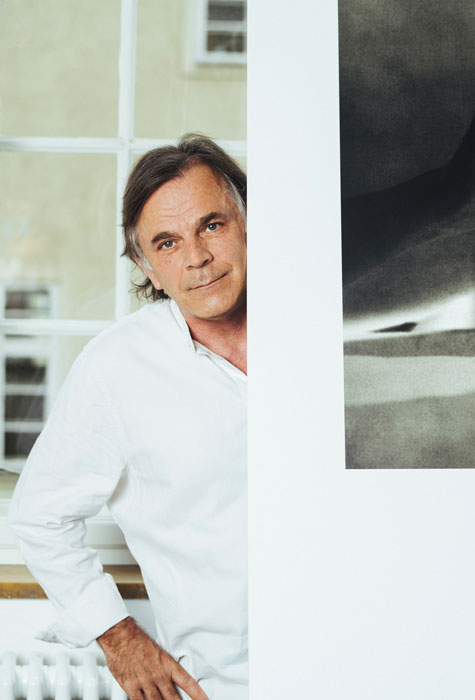

Since 2016, Markus Hinterhäuser has been the Festival's Artistic Director in a Direktorium chaired since January 2022 by Kristina Hammer and alongside Lukas Crepaz, the executive Director in charge since 2017.

His career has never really left the Salzburg Festival since, in Gerard Mortier's time, he and Tomas Zierhofer-Kin founded the Zeitfluss-Festival, a festival of contemporary music that was a dazzling success thanks to the diversity and originality of its programming, and was revived under the name Zeit-Zone at the Wiener Festwochen from 2002 to 2004. He was then called back to Salzburg to conduct concerts from 2007 to 2011, and took over as interim artistic director after the resignation of Jürgen Flimm in the summer of 2011. After taking over as director of the Wiener Festwochen from 2014 to 2016, he was appointed Artistic Director of the Salzburg Festival, a post he will hold until 2026 after renewing his contract in 2019.

But Markus Hinterhäuser is first and foremost an artist, a pianist, trained at the Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst in Vienna, at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and notably with Elisabeth Leonskaja and Oleg Maisenberg. He is an acknowledged specialist in contemporary music, and a pianist specialising in the interpretation of Lied (we know of his long collaboration with Brigitte Fassbaender).

Among the remarkable productions he has taken part in is Franz Schubert's Winterreise with Matthias Goerne and the images designed by William Kentridge, a show that has toured the world from Vienna to Aix-en-Provence, from San Francisco to Moscow and South Korea.

Markus Hinterhäuser, artist, successful cultural manager, renowned intellectual and polyglot, honoured Wanderer with a very detailed interview, giving us a better understanding of the choices made by the Salzburg Festival today, in a serene and relaxed atmosphere. The interview was conducted mainly in Italian (he was born in La Spezia), but also in French (which he speaks wonderfully well) and of course in German, in the way we like so much of those borderless intellectuals of Mitteleuropa .

Let's start in medias res.

I saw Falstaff yesterday, which really shook me up, and I'd like to know how you choose directors for operas, and in particular why Christoph Marthaler for Falstaff?

First of all, I've known Marthaler for many, many years. I've done two productions with him as pianist and manager, Schubert's Die schöne Müllerin and another production at the Wiener Festwochen Schutz von der Zukunft . I know him very well inside/outside and I hold him in high esteem. For me, he's one of the great artists of our time, one of the great directors, and he's someone who is so musical with a mind so different from the others that I wanted to ask him for Falstaff, but he had certain doubts, not about the music but about the story, certain question marks, but he had a fascination for the libretto. And then he phoned me one day and said: "Yes, I want to do Falstaff, but I have a very specific idea... Are you familiar with Orson Welles' Falstaff and The Other Side Of The Wind? "

I then understood his intention: it's a sort of intro/extrospection. He sees himself in a way, without getting into psychological or psychoanalytical considerations: he sees himself and at the same time he sees a totally disillusioned world. For me, it's really interesting: the figure of Orson Welles' Falstaff, Marthaler's sense of comedy, so particular and bizarre, his highly original world outside any convention.

And it's clear that he's offering us a demanding show, demanding for those who expect the usual Falstaff, already seen a thousand times. But I didn't want a Falstaff like that, and neither did Marthaler or Metzmacher.

So there's this idea of history within history.

I'd rather say the story within the story within the story...

Yes (laughs). But for me, the result is ultimately a moving and touching story of a great artist who met a great artist, Verdi, and another great artist, Shakespeare. I was very happy with the production, very happy with this Falstaff....

And then there were so many critics... so many discussions about this Falstaff.

It's a question of the perception of opera, much, much more difficult than the perception of symphony or chamber music concerts... There are such rigid expectations in the theatre that when a great artist falls short of or goes against those expectations, there is enormous confusion. To talk about confusion and chance, at the end of the second act of our Falstaff, there's total chaos, everything collapses, you get the impression that there's no longer any direction, that Marthaler is abandoning everything in total anarchy... yet everything is meticulously worked out! Marthaler is so generous in this production that everyone needs to keep their eyes and ears open, because I've always had the impression that Falstaff could be a play for Marthaler... I had this idea for Falstaff with him for years, it took a long time, but for me it has succeeded at a very high artistic, reflective and intellectual level. There's the intellectual side, but there's also the burlesque side where he tells a lot of stories, like in the wicker basket game where Falstaff has to hide... And it's extremely comic and at the same time absurd, in the style of Buster Keaton, but also in the style of Jacques Lecoq, because Marthaler studied with Lecoq...

I'm very happy that here we have a Falstaff that is completely, totally different from expectations, as a “Festival Falstaff” should be...

But precisely on what criteria you choose directors?

There are the 'regulars' (Stone, Warlikowski, Castellucci), others who are rarer (Marthaler hasn't been here since 2011) and some who have never been here before, like Tcherniakov...

Tcherniakov is coming in 2025...

First of all, the criteria are subjective.

There are directors I consider to be important from an artistic and intellectual point of view, in terms of their approach to the theatre... and the idea of the theatre.

And then there's intuition

There's also the question of being able to work in spaces as special as the Grosses Festspielhaus or the Felsenreitschule, which are immense spaces. It's very difficult and not everyone is capable of managing such spaces.

It's all very subjective, but I'm looking for directors who can translate works like Falstaff or Macbeth and adapt them to our times. There's no point in doing a Falstaff like overall in the world....

I also like the ongoing relationship with directors like Warlikowski, Simon Stone, Castellucci and Tcherniakov, because I like the idea of creating a family here in Salzburg. The idea of inviting one or two new directors every year doesn't really make sense. There's a great quote by Martin Kippenberger ((Editor's note: Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997) is a German painter, performance artist, sculptor and photographer)) who said, referring to Van Gogh, "I can't cut off an ear every month". What seems essential to me is to cultivate a continuity of work with the artists I consider important for the Salzburg Festival. Perhaps that will change with another artistic director, but that's my language, that's the way it is.

Let's talk about you. You were director of the Wiener Festwochen, in Salzburg you directed the contemporary music cycle Zeitfluss-Festival, you were interim director after the resignation of Jürgen Flimm, you also directed the 'concert' part of the Festival... How do you make the transition from musician to artistic director?

It all started with Zeitfluss, in the 1990s, with a friend who wanted to organise a contemporary music festival. When you want to do something in Salzburg with a certain weight, a certain importance, a certain generosity, there's the Festival. So we went to see Gerard Mortier and Hans Landesmann. ((Editor's note: Hans Landesmann (1932-2013) helped found the GMJO and Wien Modern with Claudio Abbado, was artistic director of concerts and administrator of the Salzburg Festival from 1989 to 2001, and accompanied Mortier throughout his term of office. He is one of Austria's leading cultural figures.)) We presented our project, a sort of Fringe Festival which had never been organised in Salzburg. They liked the project and we started with Nono's Prometeo, which was an incredible success. I then realised that I might have a certain talent for communicating the things that interest me in my life, i.e. music and art, even complicated things. After Zeitfluss, I did a few projects with Christoph Marthaler and Klaus Michael Grüber, and then I was asked to direct the 'Concerts' section here in Salzburg. So my relationship with the Salzburg Festival has continued, which is a great privilege for me. But I would never have done the work I've been doing for several years now if it hadn't been an artistic endeavour. The structure and organisation I have here are very efficient and very solid, and I attach a great deal of importance to the word 'artistic' in the management of the Festival. There are so many qualified people here who do an incredible job that I can take my work for the Festival in a different direction.

For me, the idea of a career strategy makes no sense. I was lucky enough to enter the world of the Festival, which for me was a closed world: for me, the Festspielhaus was a bit like the Kremlin! Inaccessible (laughs)! Today, things have changed a lot. Mortier changed a lot of things. The Mortier-Landesmann years were years of socialisation for me. They changed a lot of things in my life. I saw certain productions, for example Messiaen's Saint François d'Assise directed by Peter Sellars, which changed everything! It was a 'Change of Life'. I understood what opera could be, what a Festival could be, and that's perhaps the logical consequence of my life, which of course has nothing logical about it (laughs).

What are the duties of the Artistic Director?

First of all, to emphasise that the Salzburg Festival is an art festival. There's all the bling around it, but fundamentally it's a festival about art, music, theatre, literature and so on.

Secondly, I think it's very important to create a tone, an atmosphere in a festival. A festival is an interesting thing. I couldn't be the director of an opera house. Look, the big festivals are all in small towns: Salzburg, Glyndebourne, Aix-en-Provence, Lucerne, which are open to the whole world for six weeks. We sell 230,000 tickets, for example: it's a completely heterogeneous audience, and I have to homogenise it. We draw up a programme, we offer it to the world and then we see whether people come or not... Now, I have to say that there is great confidence in what we do, certainly with discussions around certain productions, but, even with their limitations, they give the idea of why we do the Salzburg Festival. Productions like Macbeth, like Greek Passion, have strong political themes that are important to us.

So my tasks are a mixture of all that.

You mentioned 230,000 tickets, so how many events are there?

Around 220, because there are also symposiums and so many other things around the Festival...

And in terms of budget?

We have a budget of 80-82 million euros, and subsidies cover less than 25% of that, so we have to sell tickets. This year, the demand is incredible. 95% coverage, which has a lot to do with previous years - there was also a lot of demand last year - and especially with 2020, we were the only festival to offer a programme during the corona period, and we've created a new audience, a new 'comunity' as we say in English, very interesting, with a new empathy, with a new confidence in what we do, it's... touching!

You run a festival with three departments: theatre, concerts and opera. Do you think about cohesion? How do you bring things together?

Yes, of course, we try to bring things together, but without having a strictly didactic vision.

For me, each Festival is a kind of story. The meaning of the Salzburg Festival is not to give one concert after another without any demands. We have to make people understand why we are doing a Falstaff, a Figaro, a Macbeth, a Greek Passion, or Purcell's Indian Queen, and why we are doing Berlioz's Les Troyens... because there is a thought behind it all. We don't do things by chance. It's important for me, in the face of this enormous mass of concerts and events, to have a kind of anchor, a basic moment, which then develops. We do most of the programme here after 20 September and until 20 November, two months after which everything goes to press. It's very interesting to see how things develop and appear...

What can I say? You know, I'm not young any more, I'm of the “analogue generation”, it's like the development of a photograph that appears gradually, first these shapes, then it becomes a photo, first with this yellow light, then with the contrasts, then the colours... It's very beautiful! It's a bit like that here, there's a base, very clear to me, but it develops into a lot of things, and in the end I'm like a navigator in the middle of this tide of things: it's a navigation system for me and for the audience.

The audience is also a challenge for me, because this mass of 230,000 people is constantly changing, the audience of the first week is not the audience of the fourth week, there's a constant change. How can I somehow guarantee this story, this tale that is both the same and different from one day to the next, how can I reach the audience in mid-August? At the end of August?

And then there's this “Ouverture Spirituelle” ((Editor's note: The festival now starts around 20 July with a ten-day 'Spiritual Overture' featuring concerts of sacred music, but not just sacred music)) which is very important to me, where there's total freedom in the musical choices, you can do the whole geography of music from ancient to contemporary, as long as it's always linked to something biblical or spiritual. For me, that's essential...

What sets Salzburg apart from other festivals?

First of all, it offers everything, the whole geography of music. We are not limited. Of course, there's Mozart and Strauss, Mozart above all, but Strauss too, of course, but we can do everything, from Monteverdi to the present day. There are no limits. And that's magnificent. Bayreuth has only one composer, Wagner. And then there's the dimension of the offer, unique in the world, and also the historical dimension of the Festival, these 102 years are a concentrate of the cultural history of Europe. We hope that the Festival's archives will be opened next year, and what we discover leaves us breathless, with its ups and downs, its many ups and downs... It's not a homogeneous story, it's not, but it's still incredible, starting with Max Reinhardt, Richard Strauss, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, it's something that has no equivalent today. There's no need to wonder why or how: that's just the way it is!

But what is the weight of this past? The first time I came, there were Karajan's epiphanies (theophanies?) ...

In the Karajan era, everything revolved around Karajan. The programme was all about him, and the programme was a third of what we offer today. Everything was based on Karajan's popularity and the power of the music industry, on records. That no longer exists today. Everything was filled with Deutsche Grammophon, DECCA, EMI, Philips... Now there's nothing. It doesn't matter anymore.

Mortier, with all due respect and esteem, has arrived at a historic moment for the Festival, the post-Karajan era. It's clear that you can't have a Karajan-style Salzburg Festival without Karajan. It would be impossible.

So there was this 'wind of change' and Mortier arrived at an open and transgressive moment with possibilities that were still extremely generous. And that no longer exists today. Just think that Saint-François d'Assise was done with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which is unthinkable today: it's no longer possible. That, too, is a thing of the past. Lukas Crepaz our Executive Director had a lot of problems to solve economically, and there weren't then either the problems that are strong today and will be even stronger in the years to come: what is theatre? what is permitted? All these discussions about "political correctness" didn't exist back then! The world of Karajan is no more, but neither is the world of Mortier, and to quote Stefan Zweig, it's Die Welt von gestern (the world of yesterday)((Die Welt von gestern - Erinnerungen eines Europäers/ The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European , Pushkin Press))... Everything has changed.

These are issues that interest me greatly: what is theatre? What is the mystery of theatre? It's made up of things that can't be linked to the parameters of 'correctness', to today's pseudo-morality.

We are faced with problems that are totally different from those of Mortier. And it will be even harder for my successor... There are very strong critics today, in everything we do. Looking at things with a certain irony, it might no longer be possible to play Carmen, a woman, a gypsy, working in a cigarette factory... Impossible... That's the way the world is.

In addition to the works in the repertoire, each year you offer a world premiere, or a rarely performed work. How important is the world premiere for Salzburg, and what criteria do you use to choose the so-called rare works?

As I told you, in all the years I've been in charge of programming, the important thing for me is to tell a story.

I don't really care if it's a world premiere.

I have a great passion for contemporary music. But I've done so much for contemporary music here in Salzburg that I'm now more interested in studying operas, in putting operas like Macbeth or Falstaff under the microscope to question them and understand what they tell us.

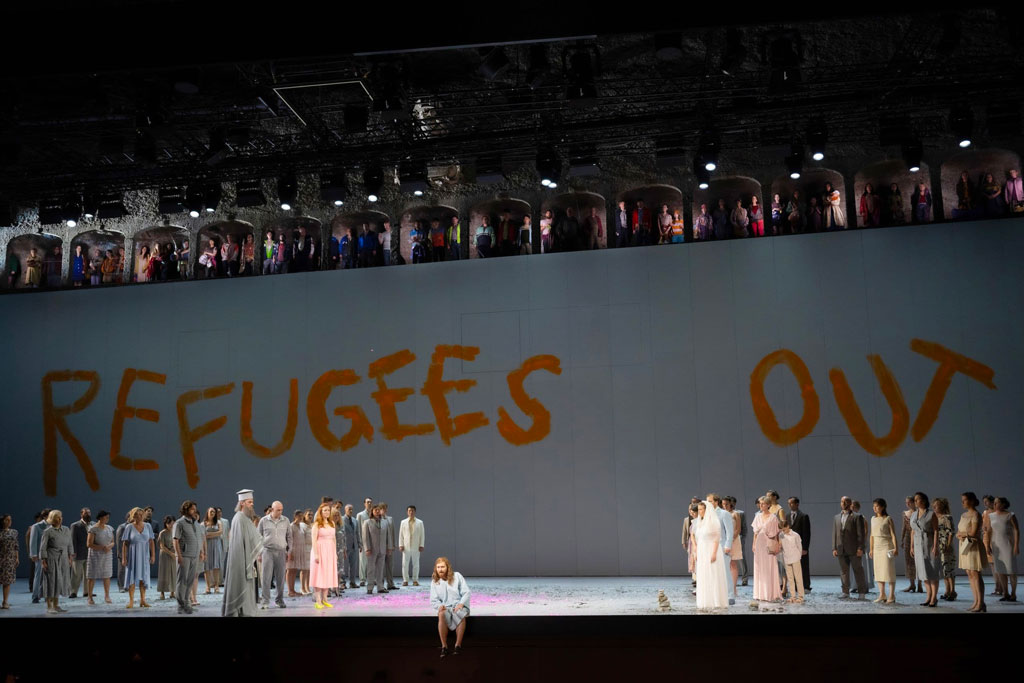

Let's take The Greek Passion now, it really is a great revelation to me for everyone. A world premiere? But doing The Greek Passion this year and Weinberg's Idiot next year is very important to me.

Perhaps I should ask myself whether I've acted reasonably, but we've already done a lot of contemporary music, Reimann, Rihm, Henze, and we'll be doing Eötvös in 2025 (The Three Sisters). In a way, it's fair to say that The Greek Passion is a world premiere... Who knew this opera? No one did! Now the whole world knows it. That's the task of a Festival... (Editor's note: And people were desperately looking for tickets because everything was sold out).

You spoke earlier of Mozart and Strauss as the emblematic composers of Salzburg, but it seems that these days it's a bit difficult to present Mozart; few productions find a consensus, both musically and scenically... What do you think is the reason for this?

It is very difficult to answer this question...

There is an idea of Mozart ... an Apollonian Mozart ... An idea of Mozart that is a bit "disturbing"... There is a very deep, really very deep, dialectical problem: The Mozart avant-garde of today is a HIP Mozart (Historically Informed Performance). It is impossible to perform a "historically informed" Mozart in Salzburg. I have to find a balance between this fact that really Historical Performance Practice, that's what Mozart is now asking for, and a scenic realisation that is clever, that is intelligent and that explores Mozart. When we do Figaro today, and we talk about the Age of Enlightenment, that's our world.

We have to ask our world differently,

Martin Kušej shows another side in his production, not the light, but the darkness, the dark side, and that really is very interesting. Kušej circumvents what is no longer relevant today, the "ius prima noctis". It doesn't matter at all...

We have to look for what is important for us today, what we can take away from this work, such as forgiveness, which is a great moment of humanity. Forgiveness is a thing that is much more important than all the petit-bourgeois things we get lost in. What is allowed, what is not allowed? But with Mozart, everything is allowed. With Mozart, everything is possible: you need honesty, intelligence and a certain amount of thoughtfulness. Mozart is so much bigger than the petit-bourgeois of his reception! Mozart allows everything, everything, he opens himself up to everything, everything, even to the dark, to the dark side, to everything that disturbs us.

You are right, it is very difficult to do Mozart today: That's why I want to repeat Castellucci's Don Giovanni next year, which is a great reflection on the myth of Don Giovanni. I find that interesting, we must have the courage to face these reflections. It's not provocation that interests me, it really doesn't. Provocation as a strategy is boring and stupid. But provocation in the etymological sense of the word "pro-vocare", to call out, to bring forth, that has a meaning.

What about Wagner? There hasn’t been any Wagner for ten years…

You can't do Wagner. With the programmes we have, it would take too long. Wagner was the composer for the Easter Festival. Then you have to reach an 'agreement' with Bayreuth. Then we have so many performances... In the Grosses Festspielhaus, which can accommodate operas like Parsifal or Tristan, between concerts, recitals and other operas, it's very difficult to fit in a five-hour or five-and-a-half-hour opera with the corresponding rehearsals.... There are too many problems.

One of the reasons why Karajan created the Easter Festival was to be able to do the Ring, because it's very difficult in summer.

I'd like to do Tristan, it's a dream, but...

Can you give us a glimpse of the future?

I will answer with an expression inspired by a beautiful quote from James Joyce ((Ulysses, I, VII, Aeolus)): "I am a man with a great future behind me"...

And you, at this stage in your career at the head of the world's biggest festival, do you still have a dream in the drawer?

I don't know, as Festival Director... yes... Doing a Tristan und Isolde would really be a dream. But it's only fair that there should be dreams... Robert Musil made this difference with dreams in "The Man Without Qualities": "Wirklichkeitssinn" and "Möglichkeitssinn". The sense of reality and the sense of possibility. It's important to always keep that in mind.

To conclude, you spoke of the difficulties facing opera today...

Is there a crisis in opera?

We're the ones in crisis. There are a lot of symposiums on the crisis of opera, and of classical music, but the crisis is us.

An opera, a quintet by Schubert, a symphony by Mahler all describe a crisis. In Mahler's Ninth, the last movement, the Adagio, describes a crisis, his crisis when everything comes undone, his death, his farewell, his farewell to tonality, his farewell to the symphony and his farewell to the entire Habsburg empire that is disappearing. There is such melancholy ("Wehmut")! But it's a description of a crisis, not the crisis itself.

We are in a very deep crisis, very frightening in a certain sense.

© SF / Marco Riebler (Testata)

© Salzburger Festspiele / Lydia Gorges

© www.neumayr.cc

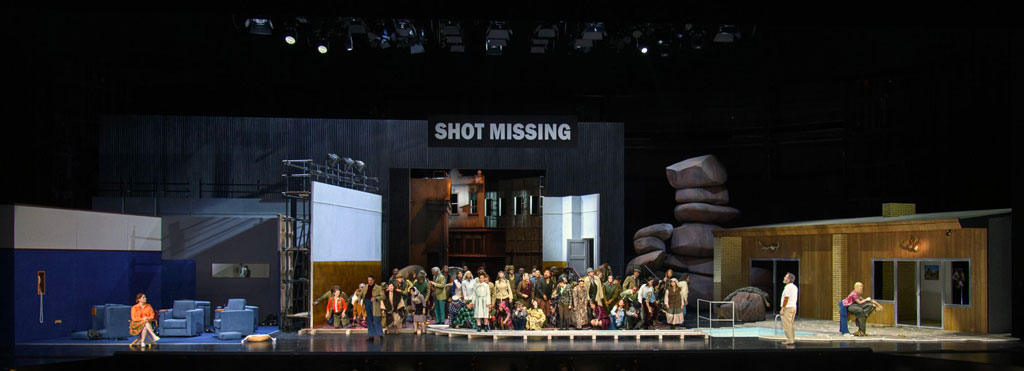

© SF / Ruth Walz (Falstaff)

© SF / Monika Rittershaus (The Greek Passion)

© SF / Bernd Uhlig (Macbeth)

© SF / Matthias Horn (Nozze)