Memories… Memories

Let's start with a memory.

Queuing at the Paris Opera at the Palais Garnier for a performance of Tosca in those days when queues lasted for hours, so you ended up chatting with your neighbours. A lady tells me that she has come back to see Tosca after seeing it some twenty years earlier with Maria Callas. She began to talk about it and started to cry.

My relationship with Elektra could be likened to this anecdote.

My first Elektra was at the Palais Garnier in 1974 with Karl Böhm in the pit and Birgit Nilsson on stage, surrounded by Christa Ludwig and Leonie Rysanek. The following year, Astrid Varnay took over from Ludwig. Eight performances in two seasons. I saw seven of them, as the eighth was pre-empted by the President of the Republic (Giscard) for some official visit or other.

Since then, I have locked all this away in my personal vault, like a kind of Elektra benchmark. The rest of my life and the many productions of Elektra I have seen with the greatest conductors Abbado, Maazel and Petrenko and the greatest Elektras of the last 40 years (Gwyneth Jones, Hildegard Behrens, Evelyn Herlitzius, Nina Stemme, Eva Marton, etc.) have not succeeded in dethroning the original benchmark. Anyone who has heard Birgit Nilsson on stage in this role knows exactly what I mean, and anyone who has heard Karl Böhm conduct Elektra also knows what a unique sound he could draw from the orchestra, in this case the Paris Opera, and with what tension he conducted. Anyone who has heard him in Elektra also knows what it means to have a torrential yet crystalline Elektra, unforgettable in the heart, intact in the memory forever. There are a few live recordings of one of the performances, for those who want to hurt themselves.

Should we then close the book Elektra ? Should we give up listening to others ? Should we give up listening to a work we love because the book was opened by four irreplaceable and irreplaceable deities ?

Of course not.

That is why my visit to Vienna in December 2025 is something of a pilgrimage. Not that I am looking for the ghosts of Karl Böhm or Nilsson, no, not really, since they remain very much alive in me. But the Wanderer-pilgrim is seeking another memory, that of Claudio Abbado's encounter with this work in Harry Kupfer's production. While I am a well-known devotee of Abbado, I have also had great admiration for Kupfer since his famous Fliegende Holländer in Bayreuth in 1978.

I saw this production of Elektra with Abbado in the pit on 18 June 1989 (with Eva Marton, Brigitte Fassbaender, Cheryl Studer, James King and Franz Grundheber) when Abbado was still the GMD in Vienna, a few months before being elected in Berlin. And more than the cast and conductor (and yet…), it was the production that left me spellbound…

I'm not here tonight to reminisce : just being at the Vienna Opera means seeing all my ghosts dance from the moment I step into the Atrium. I have seen and heard so many extraordinary things (and even a few unspeakable performances) that returning to Vienna to the Haus am Ring is like a perpetual opera ball for me, or rather a grand waltz with my opera ghosts.

Harry Kupfer's legendary production

I haven't seen Kupfer's production since. I'm coming to see it again, to relive it, and I'm also here for a cast that is undoubtedly one of the best possible today, with a conductor in the pit who is highly regarded and represents a bright future for opera, the British Alexander Soddy. The trio of ladies is Camilla Nylund as Chrysothemis, Nina Stemme in her debut role as Klytämnestra and Ausriné Stundyté as Elektra.

From the moment the curtain rises, the die is cast.

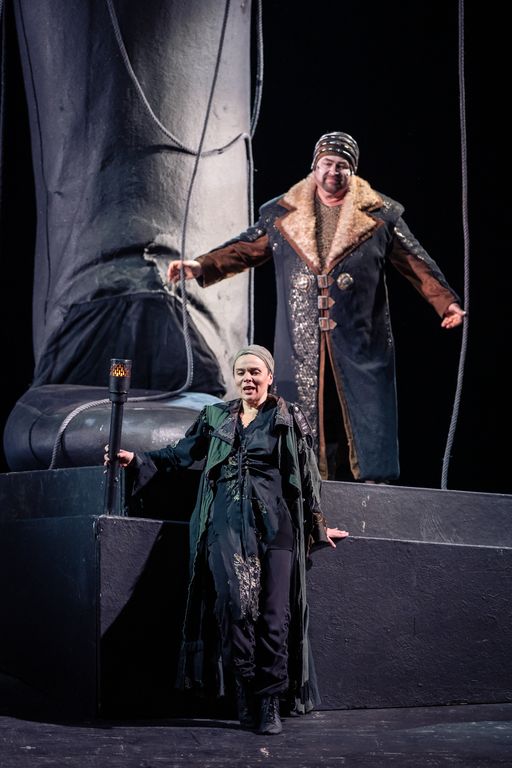

We are confronted with the immense statue of a man, a warrior of whom we can only see the leg, his foot resting on an open, dented globe, with a giant head buried in sand lying next to it. Everything is there, and everything is said about the work and the tragedy.

This immense statue is the shadow cast by memory and crime. It is what motivates Elektra's hatred, Klytämnestra's nightmares and the disappearance of Orestes, about whom we know nothing. This immense statue is Agamemnon.

There is no need to say more, no need to do more : the relationship between the tiny bodies of the servants and the main characters and this enormous, overwhelming statue, this colossus of Mycenae, says it all.

To this must be added the ropes hanging from above like bonds, as if someone had desperately tried to bring down the monumental statue, which we assume was erected as a tomb, as if these ropes imprisoned all the characters in the folds of their remorse, in the memory of their crime on the one hand and in the open wounds of their desire for revenge on the other.

This is enough to set the scene for tragedy.

Everything takes place on this statue pedestal, and it is on this pedestal that Elektra has chosen to live, locked in the half-open globe at her father's feet, constantly brooding over her revenge and at the same time crushed by the very impossibility of carrying it out.

The staging in this setting forces all the characters to visit Elektra at the foot of the statue and thus to be confronted with the young woman and physically crushed by the place of memory.

This is pure epic theatre, pure theatre of signs.

Theatre that does not get lost in detail, theatre that tells nothing other than the story of overwhelming memory and the impossibility of erasing it. And which places each character in relation to the other in the face of this wall of impossibility.

It is not a virtual, overwhelming fatality, as defined by the tragic hero[1], it is a visible and not virtual fatality that directly overwhelms each character but also imposes itself on the audience with its gigantic calf. Agamemnon is there. No one can escape it, and of course Elektra's first monologue takes on its full meaning with the famous opening question (here quite sarcastic given the situation): ‘Agamemnon wo bist du?’ (Where are you?). Visually, the 2,000 people in the auditorium have the immediate answer : Agamemnon is everywhere.

Kupfer and his set designer Hans Schavernoch impose him on the audience. One might dare to say that everything else is just literature, or rather that everything is ordinary theatre for extraordinary characters.

Kupfer is a very good director of actors and he has undoubtedly left fairly precise staging notes, but the three ladies singing tonight each know what they are singing. All three are incarnations. All three are singers with a mind of their own…

Furthermore, Reinhard Heinrich's costumes are particularly interesting and just as legible as the set.

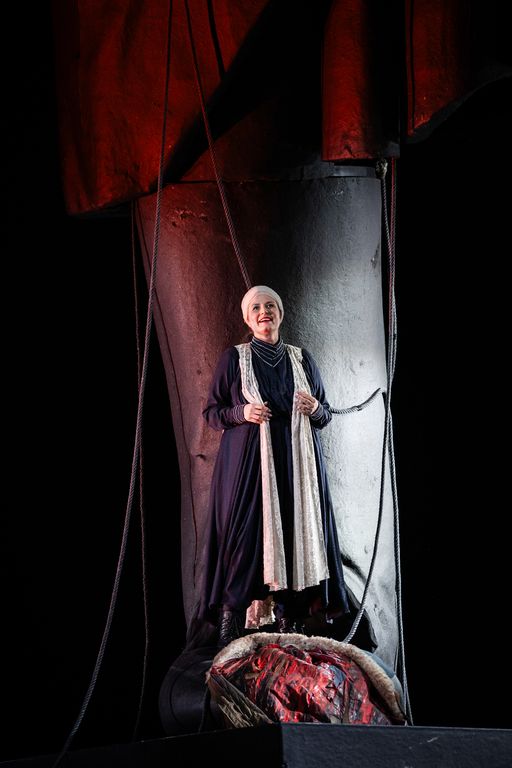

There is a similarity in style between the three ladies that clearly makes them a ‘family’: we are in the charming house of the Atreides… Each wears a similar headdress, as if belonging to the same clan, but each is distinguished by her dress. Elektra's is rather simple, that of the excluded daughter or the one who has excluded herself from the circle ; Chrysothemis's is more elegant, marked by a simple white border that doubles its lines, a dress that is both similar and different : it has the elegance of someone who is still part of the family, who takes care of herself, who would like to get married, who would like to live, and the only one who does not want the tragedy that is imposed on her despite everything. Her costume reflects this simple elegance : this is still the Empire of Signs…

And then there is Klytämnestra, the mother with her necklaces, her charms, her black dress, heavier as if it were also laden with all the memories of all the fears of this family and at the same time she wanted to avoid them, to push them away : a kind of apotropaic mourning dress, the very image of tragic contradiction. Three women, three variations of the same family, who are both similar and different. Here again, Kupfer works in plain sight.

The maids' costumes are variations on the same stylistic themes : everything in this house is struck by the same kind of curse.

What also surprises us is the ‘chronicle of an ordinary tragedy’ aspect. We understand everything, and yet we are completely captivated by what is happening on stage, and that is the magic of Kupfer's staging. This is what makes it totally timeless, both the perfect staging for the repertoire because we feel that anyone could slip into it, curl up in it and dress in it with ease, and at the same time it displays something definitive, as if there were nothing more absolute than this tragedy. We are both captivated and almost hypnotised, attracted and magnetised, we are inside and at the same time we remain outside, contemplating the spectacle of the inevitable, contemplating the tragedy. This interplay between inside and outside is fascinating. The Atreides eat you alive, like piranhas and tragic vermin all at once.

This is the Elektra effect : it is what we came for, and it is what we found.

The voices

From a vocal point of view, the stage is filled with the consistent solidity of the many supporting roles in Elektra, who sing little but always with a certain relief, such as the maids, concentrated on the first scene, notably the solid Stéphanie Houtzeel and Monika Bohinec, but among whom we note in particular the beautiful line of Regine Hangler, a particularly lively and strong fifth maid who knows how to create the necessary tension.

Traditionally, the Schleppeträgerin (alto Maria Zherebiatieva) and the Vertraute (confidante, played by soprano Ana Garotic) are entrusted to singers from the local studio, who are well highlighted, with particularly interesting timbres.

Equally customary, Orest's servant (Der Pfleger des Orest) is Marcus Pelz, a fine bass-baritone from the company, and the old servant (Alter Diener) is played by the highly experienced Dan Paul Dumitrescu, a bass who has been a member of the company since 2001.

Jörg Schneider's Aegisth (a role he has been singing at the Staatsoper since 2018), another member of the company, displays that characterful voice that makes the character immediately identifiable, detestable without being caricatural, with clear phrasing and perfect diction, not to mention a projection that perfectly conveys the game of deception between him and Elektra, with a real sense of vocal colouring. He is a singer of great quality, who knows how to make words sing, and his brief appearance is full of relief.

Derek Welton is Orest, a role he has sung several times in this production since 2020. We are familiar with this voice, which sometimes lacks expressiveness in other roles, but which is perfectly suited to Orest, who requires a kind of even tone with a beautiful dark timbre, whose power is striking here, reminiscent of the Wotan he sings elsewhere. He is the present and absent Orest we expect, and is particularly convincing, dominating the part and well engaged scenically.

Camilla Nylund is a vibrant, powerful and terribly human Chrysothemis. Her volume allows her to rise above the orchestra. Through her singing, she succeeds in showing not only the humanity of the character but also her despair. Her warm timbre, lyricism and confident high notes set her in (welcome) contrast to the more metallic timbre of Ausrinė Stundytė as Elektra, but it is in the final scene that she literally explodes, becoming absolutely overwhelming. She is one of the finest Chrysothemis heard in many years, confirming her status as one of the most intense and committed dramatic sopranos on stage, whatever the role, from Wagner to Strauss. She is simply extraordinary, at her peak.

We were obviously expecting Nina Stemme, who was Elektra, indeed the benchmark Elektra of the last 15 years, to tackle this role this time, with her voice, which remains astonishingly powerful, a role that requires in-depth work on the colours, particularly detailed in a text that is perhaps one of Hugo von Hoffmannsthal's most beautiful and which only great singers such as Waltraud Meier or Regina Resnik have been able to bring out to perfection. Stemme's style is undoubtedly less penetrating than that of the great Waltraud : she is more womanly, less incisive and more drama than tragedy, but with moments of incredible intensity and others delivered with a kind of astonishing neutrality, for example in Ich habe keine gute Nächte. She will undoubtedly continue to develop the character, but she already gives her something more ‘carnal’, less ‘thoughtful’, and she will undoubtedly inhabit her in a different way, with a voice that is still impressive in its power and roundness.

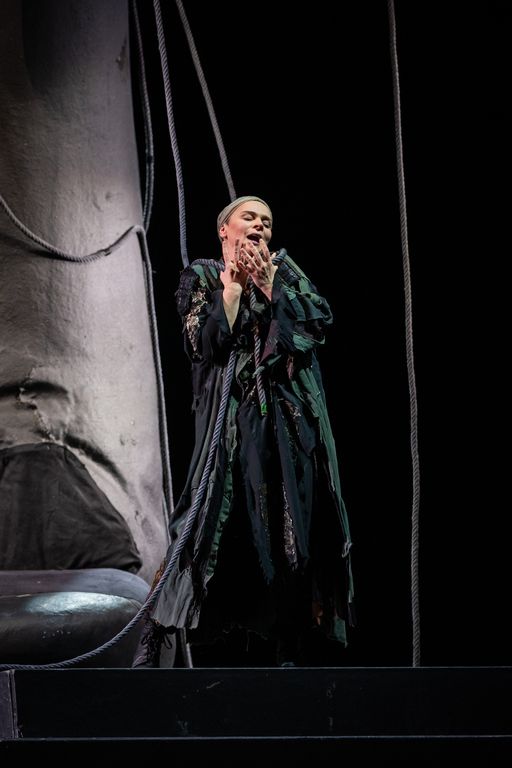

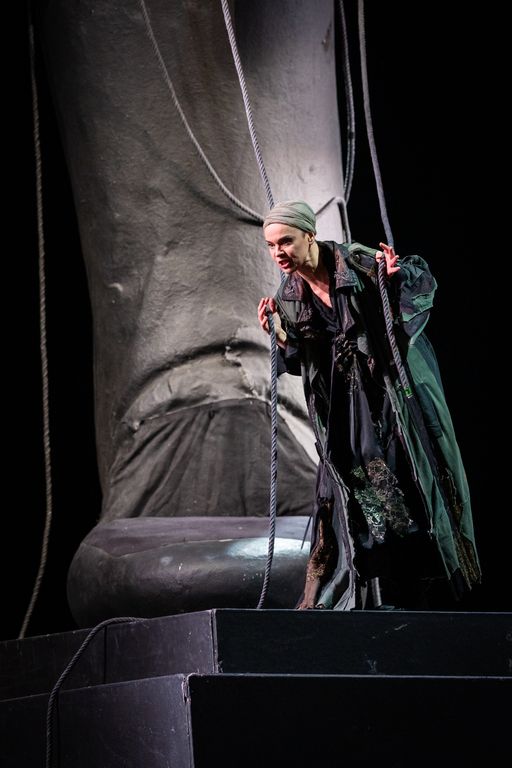

Ausriné Stundyté is now a regular Elektra on stage, and it is a role she has worked on with the greatest directors, whether Warlikowski in Salzburg or Tcherniakov in Hamburg. She therefore has a particularly deep and, above all, varied knowledge of the role. Vocally, she is not a torrential Elektra. Her voice is less impressive in volume than that of Camilla Nylund as Chrysothemis, for example. She does not have the wildness of a Herlitzius, but she possesses an incredible quality : adaptability and a sense of the stage.

Vocally, the high notes are launched and she obviously has the notes, but without the reserve of some and with a breath control that is sometimes a little short for a role of infinite power…

It is not her vocal performance per se that impresses, but her incredible stage presence. As we have said, she is a singer who has worked hard on this role, but above all she is incredibly committed to every role she undertakes, with a presence and intuition that are practically unique.

She is therefore absolutely fascinating, with her gestures that are sometimes brutal, sometimes hesitant or even fearful, her furious or imploring glances, her mood swings, her incredible impression of fragility and powerlessness, and also her absolute desire for revenge, which she knows how to convey. Elektra is a firebrand of desire for revenge, but incapable of managing it directly : she needs an arm, whether it be Chrysothemis or, soon, Orestes. And in this violence and weakness, she is incomparable.

In her own way and with her own means (which are not those of an Elektra), she too is absolutely exceptional, which is why we can say without hesitation that this is a performance of Elektra with the three singers who are undoubtedly the most committed to their roles today. And in this production, they have found a totally breathtaking field of exploration.

Elektra is indeed a special work, its success also stemming from the physical and theatrical alchemy between the three protagonists : without an Elektra who is mad with commitment, the others cannot embark on the absolute madness of the tragedy. And here, Stundyté is a prodigious catalyst.

Musical direction

In the pit, the orchestra of the Wiener Staatsoper has this work in its DNA, in its genes. We know the qualities and flaws of this orchestra, which can be totally indifferent or absolutely committed if it encounters a conductor, even for a single evening of repertoire… With 300 performances a year, it takes a lot to surprise them.

However, this is the case with Alexander Soddy, the young British conductor who has already conducted this production and who is now seen everywhere, conducting the Ring at La Scala and soon to conduct it in Florence. Let us not forget that he was Kirill Petrenko's assistant in Bayreuth for the 2013 Ring (Castorf). He is now promised a brilliant career as an opera conductor.

Conducting Elektra is, as we know, a difficult undertaking. Karajan himself gave up on it, and it is said that you shouldn't conduct it after the age of 60… Let us remember, however, that Böhm was 80 in Paris… But Böhm was a true Straussian… He was to Strauss what Toscanini was to Verdi.

Soddy, who is much younger, approaches the score with a particular enthusiasm that clearly inspires the orchestra in an absolutely exemplary performance. Some may say that it is a little strong, but that is also the character of this paroxysmal work. Others will say that the tempo is a little fast, but this helps Ausriné Stundyté in the formidable part she has to defend.

The result is, in any case, particularly spectacular, very successful with a sumptuous orchestral sound, that of the Viennese on their grandest nights. Everything remains totally under control, rhythms, textures, clarity of rendition, with a tension that lasts throughout, making the evening totally breathless. And he receives a well-deserved triumph from a delirious audience, as it should be.

Tonight, Vienna went wild and it was blissful. My ghosts would have danced to ‘Unter Donner und Blitz’ (Under Thunder and Lightning) by the other Strauss, Johann.

[1] The tragic hero contends with a virtually overwhelming fate that belongs only to him.