Premises

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is undoubtedly one of the most important works of the twentieth century, but also of the entire operatic repertoire. The melodic richness, violence, sarcasm, irony, and uncompromising portrayal of each character often make me think of the musical version of a ruthless Flaubert. There is something of Madame Bovary in this country story told in 1864 by Nikolai Leskov, not far from Madame Bovary, published in 1857.

We must consider, before Stalin's 1936 ukase, the extraordinary success of the work during the two years of life that the regime allowed it. Shostakovich's project was to produce a trilogy on Russian women, beginning with Leskov's, a symbol of oppression, patriarchy and violence in Tsarist Russia, and concluding with the triumph of the liberated Soviet woman in the third part of the trilogy.

Beyond any political considerations, the intellectual wealth of the USSR at the time and the prestige of the young Dmitri Shostakovich, considered the most avant-garde composer, who never left the USSR, whereas Stravinsky left Russia in 1914 and only returned (as an American citizen) in 1962, and Prokofiev's “inside-outside” position, which was not so clear. His first opera, The Nose, in 1928, based on Gogol, was already a huge success, and his first symphonies were acclaimed far beyond the borders of the USSR.

Shostakovich, who in 1934 created Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, was therefore already a point of reference in the Soviet cultural and intellectual world, as demonstrated by the double creation of the opera, in Leningrad at the Maly Theatre and two days later in Moscow at the Art Theatre, the theatre of Konstantin Stanislavski, the great reformer of theatre and the art of acting, whose influence is still decisive today (see An Actor Prepares or Building A Character [1]), born in 1863 and died in 1938.

Shostakovich frequented the “avant-garde” circles and personalities of the time, as can be seen in this photo, together with Vsevolod Meyerhold, the brilliant theatre director who would end up being executed in prison, a direct victim of Stalin's purges and an indirect victim of the German-Soviet pact.

This is the context of an opera whose real career began in the 1980s, written by a composer who was often accused in the West of complacency towards the Soviet regime and who navigated his entire life between drops that were sometimes even drops of blood.

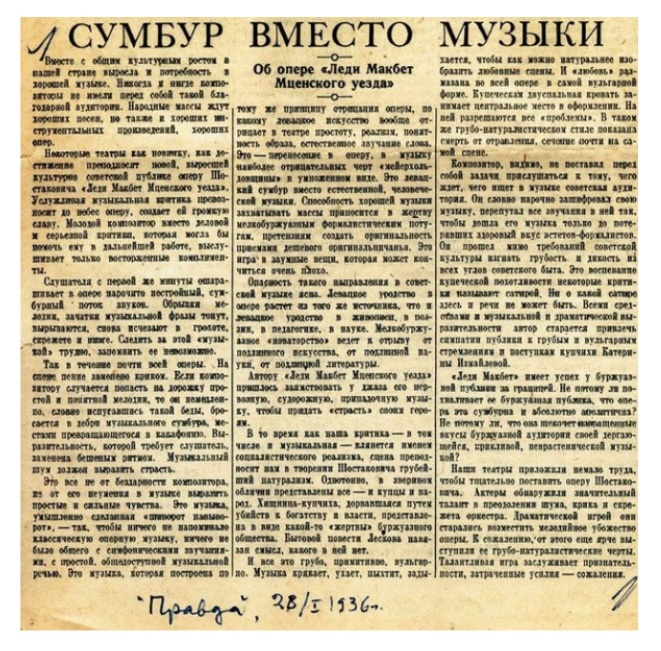

The famous article in Pravda, “Chaos Instead of Music”, directly inspired or even written by Stalin, abruptly interrupted the career of this opera, which was triumphing everywhere, with 80 performances in Leningrad and almost 100 in Moscow, a sign that it directly touched the Russian public, but not only that, as it had also been successfully staged at the MET in New York.

The article virulently attacks Shostakovich's music : “It is music deliberately made 'rough”, so that nothing resembles classical opera, which has nothing in common with symphonic sounds, with simple musical phrasing, accessible to all. It is music built on the same principle of negation of opera that characterises left-wing art, which denies simplicity, realism, intelligibility and the natural resonance of words in theatre." [2]

Immediately afterwards, the article attacks “Meyerholdmania”, then the crude “naturalism” that ignores the orientation of socialist realism. “With all the means of musical and dramatic expression, the author seeks to attract the sympathy of the audience for the crude and vulgar aspirations and actions of the merchant Ekaterina Izmaïlova.”

Finally, based on its success abroad, the article accuses the work of appealing to the “bourgeois” public : “Doesn't the bourgeois public praise it because this work is chaotic and completely apolitical ? Isn't it because it tickles the depraved tastes of the bourgeois public with its neurotic, strident, convulsive music ?”.

The stakes are clear : the young Shostakovich, aged 29, is accused of “formalism”: 'He has, as if on purpose, codified his music, mixing all the sounds together so that his music only appeals to formalist aesthetes who have lost their good taste. ‘, and thus turning his back on what socialist art should be, made up of clarity, simplicity and accessibility.

This is an aesthetic turning point that will have a long-lasting influence on the USSR (the work will be opposed for thirty years) and which also defines a deeply conservative aesthetic, what we would today call ’dad's work‘, said to be ’accessible to all". For a moment, one might say today, echoing a well-known populist rhetoric, that this music is elitist… As if the extremes, left and right, were to meet, unless they were stirring in the same pond.

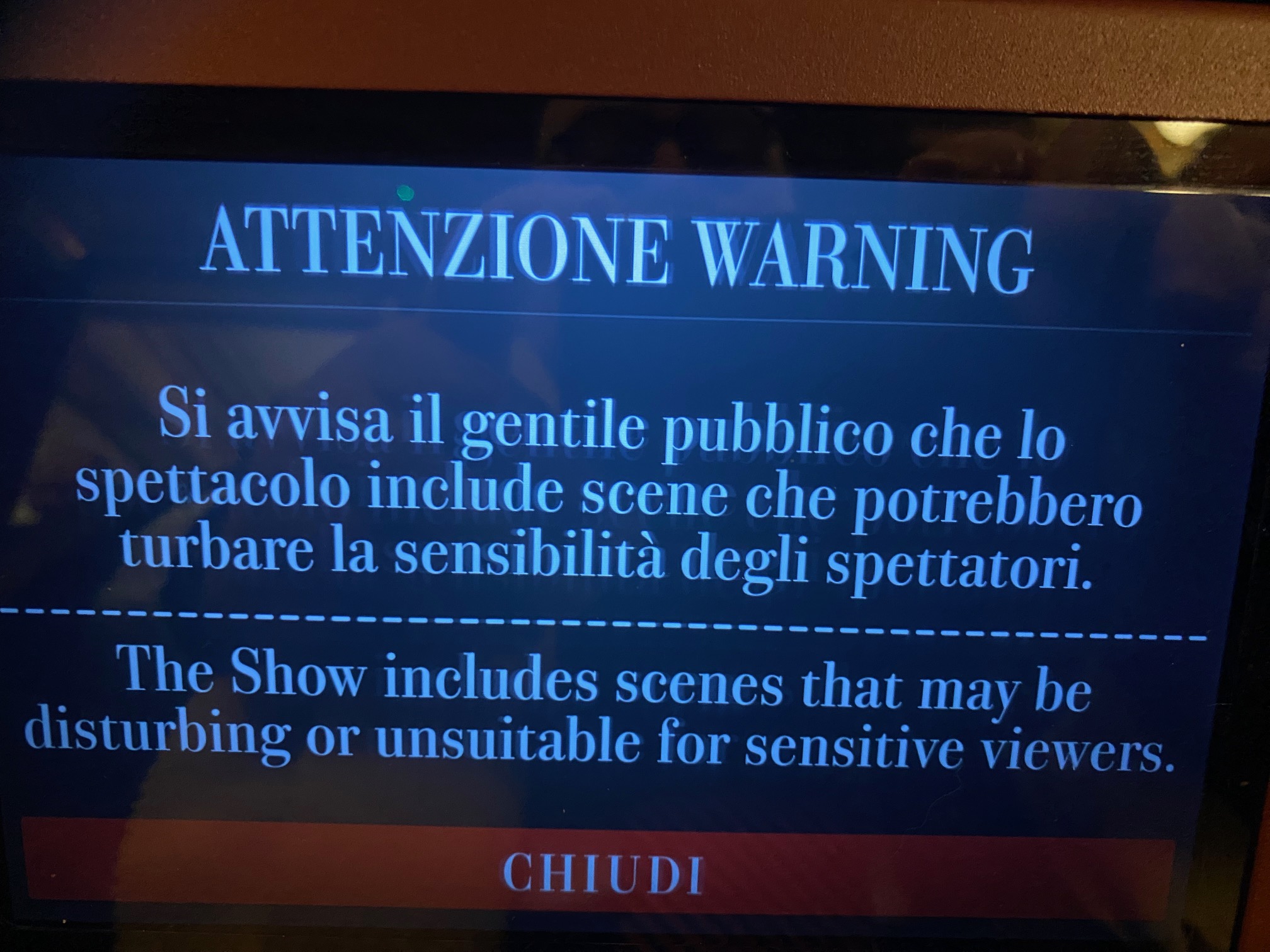

Here, then, are the facts of the debate, a debate that also found an echo at La Scala, which in 2025 (not in 1934 or 1936) deemed it appropriate to warn the public, as shown in the photo below :

Which is not lacking in salt and scents reminiscent of La Pravda at the time : “The music chatters, gasps, blows, struggles to show the love scenes in the most naturalistic way possible. And 'love” is exposed throughout the opera in the most vulgar form. The merchants' double bed occupies the central place in the staging. All “problems” are solved there.'

Right-thinking, bigotry (and ridicule) transcend the ages…

But, more seriously, both Stalin and La Scala display a sort of vision of an infantilised and unprepared, “innocent” audience, who would come to see Shostakovich believing in a Christmas fairy tale with a tree and multicoloured baubles… Should the audience of what is called “the greatest opera house in the world” therefore be warned, or even educated ? A singularly contemptuous view of the audience, whether Soviet (Stalin wanted to educate, or even “train” them) or Italian and international : ignorant people to be warned, not true conscious and adult citizens.

And it is into this trap that Vasily Barkhatov has somehow fallen, offering a production of excellent quality, but desperately “clean” for an opera that is deliberately (and here Stalin was right) raw, violent and disturbing. Barkhatov offered a television vision of an opera intended for broadcast, and therefore inevitably more “consensual”, less “shocking” and more “chic”. He must have been taught that opening the season at La Scala required “moderation”, and so here we have Lady Macbeth lacquered like a duck.

Please note, I would not want my comments to be misunderstood. Vasily Barkhatov's work is a true work of direction. He has also demonstrated his ability to produce powerful, meaningful and original performances. I simply want to point out that, by agreeing to stage the opening opera of La Scala's season, he had to submit to a series of perhaps contradictory impositions.

The opening of the season is a social event and absolutely not a cultural one, broadcast on television in prime time. This still imposes a series of rules today.

The issue concerns the opera itself.

Obviously, we should be pleased that it is possible to show Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in prime time, which is not generally the type of programme offered by television stations in this time slot. And, after all, the audience was smaller than in previous years. But on the other hand, a very large number of viewers (well over a million) watched an opera that remains largely unknown to the general public. Given these particular conditions, the director had to tone down the opera and make it somewhat “presentable” to the general public.

But Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is a raw, violent work ; through the prism of television and La Scala's Prima, it had to undergo a more aesthetic treatment that favoured spectacle over the rigorous truth expressed by the work, the reason for its long ostracism begun by Stalin and continued by his successors.

The production

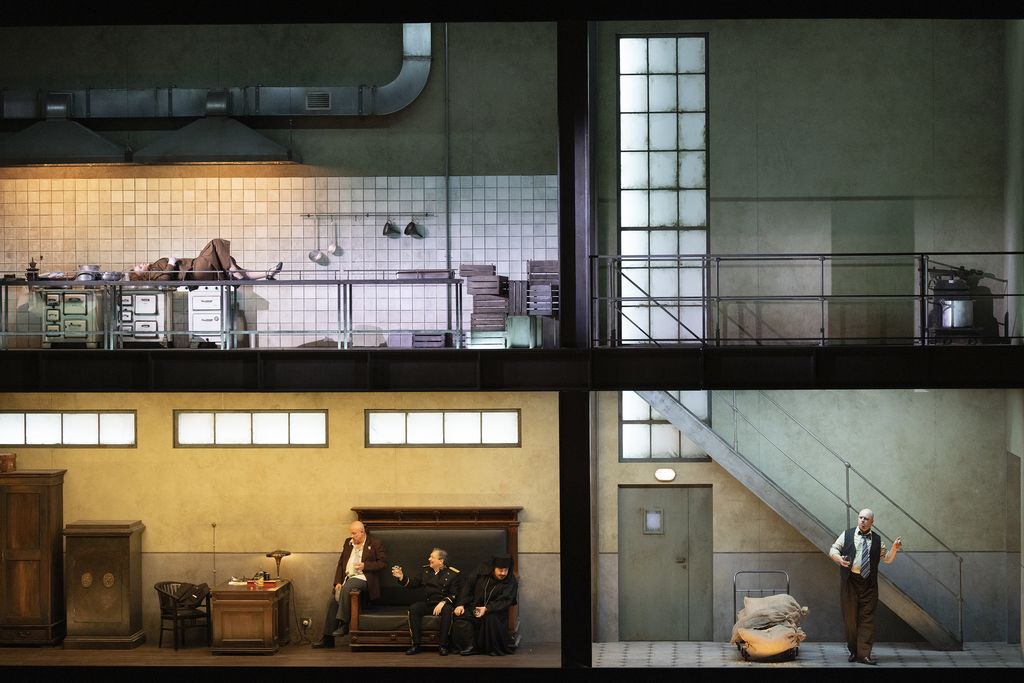

Barkhatov therefore devised two spaces with his set designer Zinovy Margolin :

essentially an “on” space, which is roughly a chic Art Déco-style dining room that, on the one hand, is a transposition of the opera to the time of its composition, thus projecting an uncompromising view of this society, attributing to it characteristics (violence, drunkenness, pettiness) intended a priori for Tsarist Russia (the opera is supposed to take place in the countryside in the 1860s) and, on the other hand, a way of sanctifying the wedding scene that takes place there (the “family lunch” scene more or less opens the opera as a motif that we will find multiplied at the time of the wedding to Sergei), but which at the same time allows us to show a façade, the bourgeois façade of family meals, of “keeping in order” . After all, Katerina always wears a rather strict brown dress (very successful costumes by Olga Shaishmelashvili), a not very seductive silhouette that somehow denies a dimension that is very present in the opera and less so in this staging, the sensual and erotic dimension.

The other space is “behind the scenes”, the “off” in a sense, which mixes both the prison and kitchen scenes. The clean and the dirty, art nouveau and grey walls, the visible and the invisible, what is shown and what is not shown. From this point of view, it is very clear, very legible and well done.

The invisible space contains the kitchen scenes, i.e. the world according to the servants, which is also a world of direct violence (the rape of Aksin'ja) without masks or gloves, and then the prison scenes, because Barkhatov also plays on flashbacks and stages the interrogation of Katerina and others who somehow tell the story during the musical interludes that usually serve as scene changes. So what we see in the dining room is also the result of exchanged glances, a sort of mental projection, a story within a story.

In constructing his staging in this way, Barkhatov plays on two universes : that of Katerina, dirty, that of the prison and the hidden one of the poor illiterate peasant woman, and that of the clean, dreamt of by the landowner who has earned her stripes, even at the cost of committing a crime. He emphasises the woman's journey, overexposing the space of success and that of failure, going beyond Leskov's story.

We are no longer in a peasant story, but in a sort of urban story that somehow transcends the ages with a few small anachronisms : in the world it describes, Katerina's illiteracy is less understandable, more justified if one follows Leskov's novel, but the overrepresentation of the authorities, the police and religion that surround Boris and magnify his funeral is much easier to understand

but also Katerina's wedding and its numerous guests.

In this vision, eroticism, sensuality and desire are less evident than the violence or vulgarity that pervades all the characters, one might say all the figures, main or secondary, most of whom are intoxicated by alcohol : the priest, for example, is drunk and unable to perform his duties, and Barkhatov “replaces” him with one of those present. Sergei is not a sex bomb, and the fact that both Sergei and Zinovy are shown in unflattering underwear reveals them in their own misery as sad males.

In the intimate scenes, we are shown Katerina's sexual misery, but at the same time, what could be a reason for her desire for Sergei is eliminated. The sordidness is very much present, but the frustration of the woman who married an impotent man remains much less visible and legible, and therefore an important part of the character's psychology and motivations remains less valued. We are a thousand miles away from the ball of desire and frustrated sensuality that was Aušriné Stundyté in both Bieito's and Tcherniakov's visions.

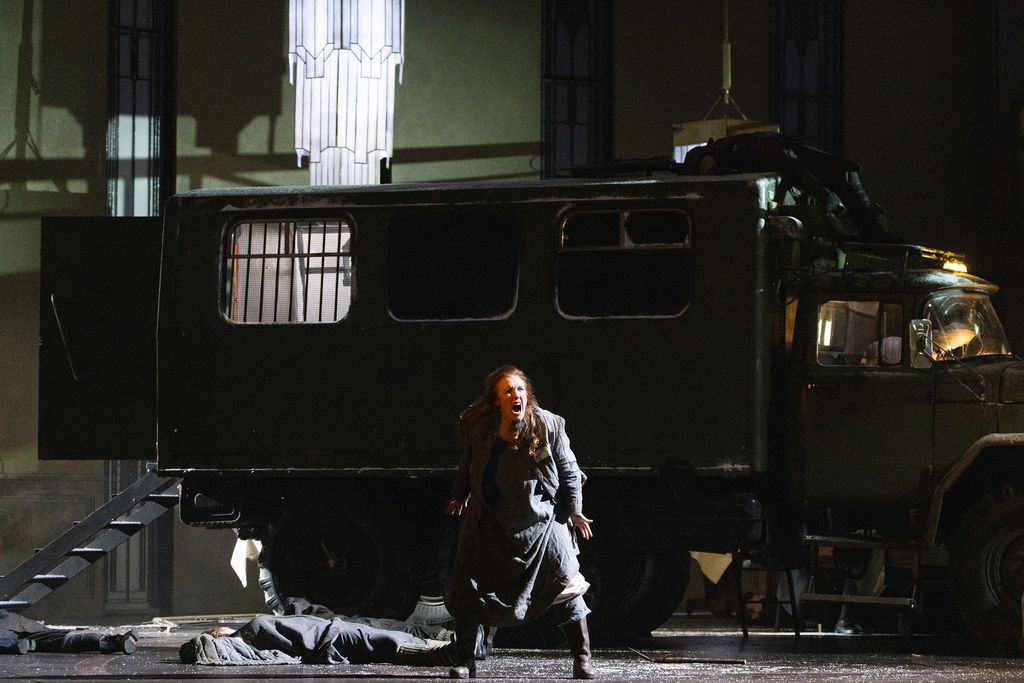

But the fundamental problem is the last act, the march to Siberia, because with his initial choice, Barkhatov cuts his own wings, so to speak, and forces himself to propose solutions that are no longer in line with the spirit of the opera, but which, on the contrary, become too spectacular, too superficial and empty the whole finale of meaning.

The dramaturgy of the last act could be summed up simply by the expression “the Tarpeian Rock is close to the Capitol”. The last act is, after the wedding feast in the form of a triumph attended by all the authorities (except the police, an opportunity for Shostakovich to take a sarcastic look at the police authority), the return to mud and sordidness in a manner quite similar to the beginning of the opera, if we refer to Katerina's loneliness and the way she is treated by her father-in-law, which psychologically recalls her loneliness in this last part of the opera.

But the situation is different. The opera shows that this endless march to Siberia is at the same time a long march to torment, where there is no solidarity among people who share the same fate, where there is no more love, where relationships between human beings are reduced to negotiations for survival. A sort of Passion.

Katerina is confronted with the most sordid human feelings. The misfortune she is experiencing is in some ways structural : it is in evil that the truth of men and souls is revealed. Sergei had used Katerina as a springboard for his own social advancement, and it is even predictable that, if the coup had been successful and Zinovy's murder had not been discovered, she would have ended up being treated by Sergei more or less as her stepfather Boris treated her. Her fate was sealed.

The situation in this fourth act thus reveals Sergei's true nature : blaming her for his situation, he abandons her and seeks his fortune elsewhere. In the absolute misery of these prisoners walking in the cold, Katerina still represents a remnant of bourgeois life with her woollen socks and arouses envy. For some, she still represents something akin to a privileged person. Thus, Sonjetka represents those who try to get by in this universe by any means necessary. She is a sort of avatar of a prostitute who monetises her service to Sergei by asking for Katerina's socks : there are no more feelings anywhere, only relationships of interest.

For Sergei, it is an opportunity to humiliate Katerina once again and isolate her a little more, pretending one last time to be in love in order to steal her famous socks. Sordid.

This whole game is obviously consistent with the situation of a convoy advancing step by step (literally), in the mud (literally and figuratively) and in the cold. This whole game is obviously consistent with a minimalist no-man's‑land scenario.

But Vasily Barkhatov has created this fixed dining room set, to which he has added a few prison or back kitchen walls that appear and disappear. Either he leaves this set, or he makes it disappear at the risk of giving up what constitutes the stylistic and aesthetic unity of his production.

He chooses stylistic and aesthetic unity at the expense of dramaturgical inconsistency.

In fact, she leaves the door of the set broken down by a prison lorry (corresponding to the period) that invades the entire space… But this makes the whole idea of the march and even the cold disappear. The lorry is the only set in the act, both inside and outside, with the interior of the cab serving, for example, for Sergei and Sonjetka's amorous games. No more moorland, no more infinite and empty space and, of course, no more final lake where Katerina will go to drown herself…

Another solution must therefore be found, and the one he finds is both spectacular and unbearable : Katerina douses herself in petrol and burns Sonietka, bringing two human figures burned alive onto the stage in 10 seconds (played by two particularly daring stuntwomen). The smell of petrol fills the hall and the front rows feel the heat. It is a purely theatrical effect designed to serve the grand finale of the premiere, to the detriment of the truth of the opera.

The truth of the opera lies instead in the disappearance of Katerina and Sonjetka into the water, which obviously recalls the disappearance of Wozzeck, another opera about sordidness that Shostakovich, who was particularly attentive to musical innovations and followed them closely, knew well, given that Berg's opera was created in Leningrad in 1927. This ending, with Katerina sinking into the water to the sound of a funeral chorus, is reminiscent of some of Mussorgsky's choruses and even the ending of Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades, because it is a way of sanctifying her. It is a kind of elevation that the ending chosen by the director, on the contrary, destroys.

He therefore chooses a spectacular and superficial ending, instead of emphasising the unfathomable melancholy of an ending in a frozen lake. In our opinion, this is a problematic choice that kills something of the opera without adding anything fundamental…

Overall, we are faced with a staging that is undoubtedly elaborate, undoubtedly very well crafted (with beautiful lighting by Alexander Sinaev), undoubtedly a true theatrical production. It remains questionable in its fundamental choice to remove anything that might shock sensitive souls and to make her a somewhat “family-friendly” Lady Macbeth, but it still shows this La Scala audience, so reluctant to accept (real) directing, what this art is all about. For this we must thank Barkhatov, because even if he has created a “circumstantial” staging here, it is interesting in that it contrasts with all the scenic mediocrity that La Scala has proudly shown us in recent years. In terms of the story, it will therefore be more interesting than memorable, but artistically soon forgotten…

The musical aspects

La Scala's strength lies in its internal resources.

Often blinded by the gold and prestige of this theatre, as well as by its past and the stars who have sung there, we forget an essential and permanent element that has always characterised La Scala. This is its internal resources. Both the technicians of all kinds, magnificent examples of commitment and quality, and the artistic forces, the choir and the orchestra.

La Scala's choir remains one of the finest opera choirs in the world, always magnificently prepared (by Alberto Malazzi since 2021) and in all repertoires.

Beyond anything that can be said about the quality of this or that production, the Teatro alla Scala choir remains a formation of excellence, “the” benchmark in the Italian repertoire, where it is absolutely unrivalled, and particularly remarkable in all other repertoires, including the Russian one. It proved this to us a few years ago during the inaugural Boris Godunov (2022–2023) and proves it again this year in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, where the choir plays a particularly important role. Whether in scenes of violence or triumph, or in the much darker final part, it displays enviable flexibility, clarity and power, spreading an incomparable emotion, particularly at the end.

The “Prima” also serves to show the world the quality of the theatre in operation and the quality of its forces. From this point of view, the choir hit the mark from the first to the last performance of the series…

The other point of reference is the orchestra, perhaps less appreciated today than it was a few years ago. It is true that other opera orchestras can compete with it, such as the Bayerisches Staatsorchester in Munich, the Staatskapelle in Dresden, the Gewandhaus in Leipzig or the Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper. The fact remains that the Teatro alla Scala orchestra remains an international ensemble far superior to that of other Italian opera houses, with an enviable symphonic level that was reinforced by Claudio Abbado's founding of the Filarmonica della Scala in 1982. This is an orchestra that has been conducted by the greatest conductors on the planet throughout its history. A legend such as Carlos Kleiber conducted it in Verdi's Otello (for the last time in 1987, on the centenary of its creation there) and in Puccini's Bohème, even though he was known to travel little. Karajan conducted it fairly regularly in the 1950s and 1960s, not to mention personalities such as Georges Prêtre, then booed in France and adored at La Scala, or Wolfgang Sawallisch, who conducted the first two days of Ronconi's Ring des Nibelungen and the entry into the repertoire of Die Frau ohne Schatten, for example. Obviously, all the great Italian conductors have passed through La Scala, there is no need to go over that again…

Musical direction

Riccardo Chailly opens his final season at La Scala as musical director with one of the operas he holds most dear.

Riccardo Chailly's work has often been noted for a certain distance, a certain coldness, but also a real attention to detail, a taste for somewhat unusual versions, without, however, always perceiving a total commitment, body and soul, to an opera.

It is no coincidence that he chose this title for his last season opening : it is highly emblematic and demonstrates an artistic and emotional attachment to this repertoire. Without him, no artistic director (not even the rare ones who have ideas) would have had the (somewhat absurd, according to some) idea of putting it on the bill on 7 December.

We must be deeply grateful to him for this and simply acknowledge that it is one of his most successful and best-defended interpretations of his entire tenure.

Riccardo Chailly is a conductor of great accuracy and precision, rather “rigid”, who favours construction over the intermittences of the heart and emotions. He is a lover of exact chemistry, who knows how to measure volumes particularly well (sometimes overusing fortissimo…), without ever letting himself go, and who often seems to enclose the orchestra without leaving it too much room to breathe. But he knows when to enhance the colours, which is noticeable in his Shostakovich, while it is not always noticeable in his Verdi, for example.

This is a very high-level, very committed interpretation that does justice to the work, but also enhances the La Scala orchestra, with some truly stunning moments in which Riccardo Chailly succeeds, through instrumental interplay and the enhancement of individual registers (the wind instruments!) the more “strange” sounds that Shostakovich is so fond of, to bring out all the sarcastic or ironic aspects. Through the subtle play of silences or the modulation of volumes, he brings the score to life, allowing the characters and situations to breathe in a way that demonstrates his total adherence to the work and its spirit.

Everything else is a matter of taste, everything else is a matter of nuance. For my part, while I greatly admired this highly studied, very full-bodied, very clean interpretation, with its magnificent result, perhaps I found it too clean, perhaps I am more inclined towards interpretations that are a little more abrupt, a little more brutal, a little less “aestheticising”… There is certainly a splendid roundness to this reading, but my taste pushes me towards steel blades…

The fact remains that the conclusion is clear : the La Scala orchestra conducted by Ricardo Chailly played in an exemplary manner and the conductor defended the opera with a warmth, energy and dedication that deserve applause. It was admirable.

The voices

As always in this theatre, when the stakes are high, the castings are indisputable, and this is all the more exemplary in that, for once, it contains no stars. No Netrebko on the horizon.

The enthusiasm with which the audience welcomed the entire cast is indicative of that often peculiar Milanese audience, which took me back to what La Scala's audience was like many years ago. It was certainly a difficult audience, which could boo Pavarotti or Caballé wildly, but which was ready to welcome an unknown singer and give her a triumph if her performance was worthy of the venue. We remember Cecilia Gasdia's first triumph in Anna Bolena, in which Caballé had to withdraw after one of the most turbulent premieres of the last forty years.

Today's audience is much more “polite”, one might even say sterile, but as I said, the fact that the standing room in the loggione was completely sold out for this latest performance showed that word of mouth, good old word of mouth, worked just like in the good old days.

And so the opera was perfectly defended by an absolutely impeccable cast, with, as usual, a team of very well-played minor roles, which is essential because in this opera the minor roles are numerous and very distinctive.

It is therefore necessary to mention them first of all, both the excellent Alexander Kravets (a peasant in rags), Valery Gilmanov as the pope, with his powerful and expressive bass voice, in the tradition of alcohol-ravaged clergymen, Guillermo Esteban Bussolini, member of the Academy (a foreman), Oleg Budaratskiy (a police sergeant) with his immediately noticeable sumptuous timbre, which emphasises Shostakovich's ruthless view of the police (something that must have pleased Stalin…), Renis Hyka, member of the choir (a drunken guest), Laura Lolita Perešivana (a convict), Goderdzi Janelidze (an old convict), Chao Liù (a guard, a mill worker), Xhieldo Hyseni (member of the Academy) (a sergeant and, tonight, a guard) Huanhong Li (a policeman), Vasyl Solodkyy (a teacher), Haiyang Guo (a coachman), Antonio Murgo, Joon Ho Pak, Flavio D'Ambra, all three members of the chorus in the roles of three workers.

The main roles must be particularly well characterised, as the interventions are generally short (with the exception of Katerina), marked, profiled and often require a real theatrical sense that can emphasise the text. It is music that is staged, that in some way shows itself. It is essential that each role is a character, a profile and constitutes a moment.

This is the case with the two secondary female characters, Aksin'ja, raped by the entire kitchen brigade (Ekaterina Sannikova), and Sonjetka, who steals Katerina's Sergej on the road to Siberia (Elena Maximova), who in some way act as a counterpoint to Katerina.

Ekaterina Sannikova is a very distinctive Aksin'ja, a beautiful actress (she studied both singing and theatre), young, with a dark-toned soprano voice that produces a rather incisive effect. She is an example of a secondary role that must “explode” in the opera.

The other example is Sonjetka, who only appears in the last act but is nevertheless essential as she is Katerina's rival, stealing Sergei from her and being dragged to her death by a desperate and suicidal Katerina. The character is terrible, mocking, very well defined, and requires a very confident singer-actress. Elena Maximova is a mezzo-soprano already well established in her international career, in particular as a much sought-after Carmen. This role requires a singer with a strong personality, and that is exactly what we have here : contemptuous and detestable to just the right degree, with a well-projected voice and violent, marked sounds that illustrate the crudeness of the character. She is extraordinary.

Alexander Roslavets is a well-known bass on the international opera circuit. A member of the Hamburg company, where he plays major bass roles (we recently heard him in Ruslan and Ludmilla as Svetasar, a noble bass, but also in Tcherniakov's Salome, and elsewhere in Boris in Toulouse, or in War and Peace in Munich, for example. Very committed to the staging, he plays a brutal character, a predator. He combines beautiful expressive qualities with a very sonorous voice, which projects powerfully in the Piermarini hall, with particularly incisive accents that make him one of the best Boris Izmaïlovs we have seen recently.

The other Izmaïlov is Zinovy, played by Yevgueny Akimov, a rather thankless role that appears episodically, a tenor voice that must contrast with its pallor the powerful voice of his father (Boris), but also that of Sergei, also a tenor, but of a different type.

So Katerina has an impotent tenor Zinovy as her husband and a “super-powerful” tenor Sergei as her lover… At least, that is how the vocal distribution seeks to harmonise the roles, so to speak. And without in any way detracting from Akimov's performance, he knows how to interpret this fundamental insignificance of the character wonderfully, giving him the dull colour necessary to musically colour the atmosphere desired by Shostakovich. A Zinovy as flat as his electrocardiogram… and therefore a very apt performance.

Opposite him, the other tenor, Sergei, is played by Najmiddin Mavlyanov, who has a more lyrical timbre than some more powerful and aggressive Sergeis such as John Daszak, which brings him a little closer to his “rival” Zinovy. Of course, there is something less opaque, more decisive, more vigorous in this singing, without the profile of the “male” full of power and eroticism that can also be seen in some productions. On the contrary, the staging cancels out this aspect in order to bring the two characters closer together and make them pitiful variations of provincial males fighting in their underwear for the female, a Katerina thirsty for “something else” who has to settle for these bodies in boxer shorts/vests that do not exactly inspire dreams. There remains in him, in his expression, in his phrasing, something a little rough, but not too much, a little primitive, but not too much, which colours his interpretation and shows real work on expression and on how to chisel the text.

Sara Jakubiak is not a singer who makes me dream a priori. She has not always convinced me, except perhaps in Salzburg in Bohuslav Martinů's “A Greek Passion” in 2024. But in the role of Katerina, she lights up the stage with a powerful, rounded, perfectly poised, projected, wide voice of rare expressiveness and exemplary commitment. She embodies this initially submissive character who meditates on her revenge while dreaming of a brighter future. Barkhatov makes her a rather introverted character, without ever eroticising her : he decisively eliminates this defining aspect of the character, frustrated by a failed and undoubtedly unconsummated marriage. She is always tense, conveying genuine emotion, with singing that remains controlled and of rare precision, particularly in the way she sculpts the words. It is a role she plays to the full. She is the real winner of the evening, and she particularly deserves it.

Overall, a musically sumptuous evening and a polished, crafted, finely chiselled production, even if the theme and the way the atmosphere of the opera was conveyed did not win me over. The fact remains that it is by far the best opening production seen at La Scala in years.

[1] Konstantin S. Stanislavski, An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, Bloomsbury Revelations

[2] About the Pravda article, you can read : https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/soviets-condemn-shostakovichs-lady-macbeth-mtsensk-district. There is also an article on Wikipedia in : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muddle_Instead_of_Music