Premise

Ruslan and Ludmila, considered the first Russian national opera, opened the renovated Bolshoi Theatre in 2011 in a production by Dmitri Tcherniakov conducted by Vladimir Jurowski. A DVD by Bel Air Media has preserved this production for readers to enjoy.

Ruslan and Ludmila is being performed this season by the Bolshoi, now directed by Valery Gergiev in collaboration with the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and, in keeping with ‘normalisation’, it is the Mariinsky production that is being performed, directed by the less imaginative and more ‘acceptable’ Lofti Mansouri.

Sic transit…

Ruslan and Ludmila was originally a poem by Alexander Pushkin, published in 1820, which he shaped into a fairy tale consisting of a prologue, six songs and an epilogue that tells the story of the abduction of Ludmila, daughter of Prince Vladimir of Kiev, by a sorcerer, then her liberation after many adventures by the knight Ruslan.

The opera libretto based on this plot was to be written by Pushkin, but his death in a duel forced a rethink of the project, which was written by several authors, and can thus be ‘untangled’:

On the day of Ruslan and Ludmila's wedding, Ludmila is kidnapped by an evil sorcerer, the dwarf Chernomor. Ludmila's father, Svetosar, promises her hand in marriage to whichever of the three suitors (Ruslan, the chosen one, and the other two, Farlaf and Ratmir, who had been rejected) brings her back. (Act I)

Each sets out in search of Ludmila, and Ruslan meets a kind sorcerer, Finn, who reveals who has kidnapped her and what he must beware of. He also tells him his own love story with Naïna, a wonderfully beautiful but now elderly sorceress, whom he no longer loves but who has become madly in love with him. She therefore wants to take revenge on Finn, who spurns her, and consequently on Ruslan, whom Finn protects, by allying herself with Farlaf, his rival.

Ruslan therefore searches for weapons and finds a sword in the giant head of a decapitated giant (by Chernomor, the evil wizard), who in turn tells him what to do and whom to guard against. (Act II)

At Naïna's magical castle, young women seduce passers-by. The young Gorislava appears, once seduced by Ratmir who abandoned her, then Ruslan arrives and, seeing Gorislava, forgets Ludmila. But Finn appears to promise Ludmila to Ruslan and Gorislava to Ratmir. (Act III)

In Chernomor's magical gardens, Ludmila thinks of Ruslan and Chernomor puts her to sleep… Ruslan arrives, fights Chernomor, defeats him, and, accompanied by Ratmir and Gorislava, decides to take the sleeping Ludmila back to Kiev. But on the way, Ludmila is kidnapped again. While Ruslan goes back to look for her, Finn the good wizard gives Ratmir a magic ring that will wake Ludmila. (Acts IV and V).

It is Farlaf, with the help of Naïna, who has kidnapped Ludmila to take her back to Kiev and make people believe that he is the young woman's liberator, but he is unable to wake her up. Ruslan, Ratmir and Gorislava then arrive, and Ruslan uses the ring to wake Ludmila ; everything is resolved, and all's well that ends well. (Act V).

A production to be viewed from above and below

Alexandra Szemerédy and Magdolna Parditka turn this rather complex plot into a contemporary story, or at least show how this fairy tale reflects particularly topical themes, as fairy tales often do, and not only since Bettelheim.

In this tale, there is no trace of a mother, and the young Ludmila is in fact without any family support. The only ‘maternal’ figure in terms of age would be the witch Naïna, who is, on the contrary, a fierce ‘opponent’ in the narrative structure, a little like Snow White's stepmother.

For his part, Svetosar, the father, is all-powerful, obviously deciding the life and destiny of his daughter, who has certainly chosen Ruslan, but once she has been kidnapped, the father decides to give her to whoever brings her back : Ludmila is a pawn in the patriarchal game, and the knights, Ruslan, Ratmir, and Farlaf, are competitors in the quest to win the missing trophy, Ludmila.

This story shows certain universal themes that can be found in medieval epics as well as in those of the 16th century by Ariosto and Tasso and their contemporary or later extensions : the magical castle of Naïna, with its young women who lure young men into a trap ; is the island of Alcina brought to life by Handel's opera, but could just as easily be Klingsor's kingdom with its flower maidens from Wagner's Parsifal.

The same goes for the magical gardens of Tchernomor, where Ludmila tries to resist all the enchantments. Tchernomor the dwarf is a force that cannot be seen, but which acts, and the two directors thus liken him to death, which rightly brings them closer to the myth of Orpheus, who goes to the Underworld to find Eurydice, who has been taken from him.

Tchernomor kidnaps Ludmila and Ruslan goes in search of her to the ends of the earth.

Alexandra Szemerédy and Magdolna Parditka thus construct a more contemporary imaginary world where, if marriage is the world “above”, the entire plot takes place in the world ‘below’, a kind of hellish world symbolised in their set design (they are responsible for the staging, sets and costumes) by the underground, where an underground life dedicated to ‘mobility’, as we say today, reigns, but which is also teeming with other lives, homeless people, shops and graffiti. And, in the reality of today's Kiev, where this story of yesterday takes place, the underground is also a shelter from bombing, even a school, even a temporary refugee camp with beds in stations or carriages : this is an aspect that they do not address but which inevitably comes to mind. The metro is therefore a world unto itself, and they exploit all its possibilities, much as Luc Besson did in his 1985 film Subway.

Thus, without resorting to a geopolitical or ideological interpretation that heavily evokes Kiev, the war in Ukraine and today's Russia, Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy explore the clashes between the social traditions conveyed by fairy tales (patriarchy, the status of women, the psychological retreats of the characters) and the real-life situations of today's heroes in societies bound by a more or less totalitarian order

A few examples…

The world ‘above’, that of marriage, is a well-ordered, geometric world, and above all well-regulated by a military order, as shown by the soldiers surrounding the celebration, but even above this, it has its marginal ‘counterpart’: the set installed on a turntable shows the ‘other side’ of marriage with famous graffiti by Banski, a world of marginality into which Ludmila will sink…

The world ‘below’ is more confused and disordered, like all subways around the world (here, old carriages reminiscent of the Moscow metro, with signs in Russian), with outdated telephone booths, graffiti of varying aesthetic quality, and stalls, and so many adventures can take place there.

Thus, the famous decapitated monster's head where Ruslan finds the sword is here a metro carriage seen from the front with its blinding headlights in an impressive and equally ‘unreal’ or ‘surreal’ image. Ruslan stands in front of it, as if to throw himself under it, and finally resists. The two directors use the original story, transposing it metaphorically into a situation that perhaps better reflects the power of the drama.

Similarly, they draw on their idea of the characters' adventures in a fairy-tale world where social and gender norms are set in stone.

In reality, in this story, Ludmila disappears from marriage, i.e. from the imposed social and patriarchal order, to live another life, which may also be a liberation, as do the three heroes, Ruslan, Farlaf and Ratmir. Everyone disappears at the end of the first act and escapes from the initial Kingdom.

Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy are Hungarian, from an illiberal Hungary where the issue of gender and homosexuality is highly political and where regular protests against the Orban government are taking place (the same could be said of Russia and elsewhere…). They therefore raise the question of the ‘heteronorm’ asserted by fairy tales, where the valiant heterosexual knight marries the young girl who is waiting for nothing else. They ask the question, ‘Does the princess really need Prince Charming on his white knight to find happiness?’

And to show this ‘ideal’ norm of happy heterosexuality, they will start from the truly excellent idea of making Ludmila a figure skating champion, with a demanding and oppressive father who is also her coach (figures of parents of skaters that we often see in this sport), who does not forgive any mistakes, through video images by Janic Bebi.

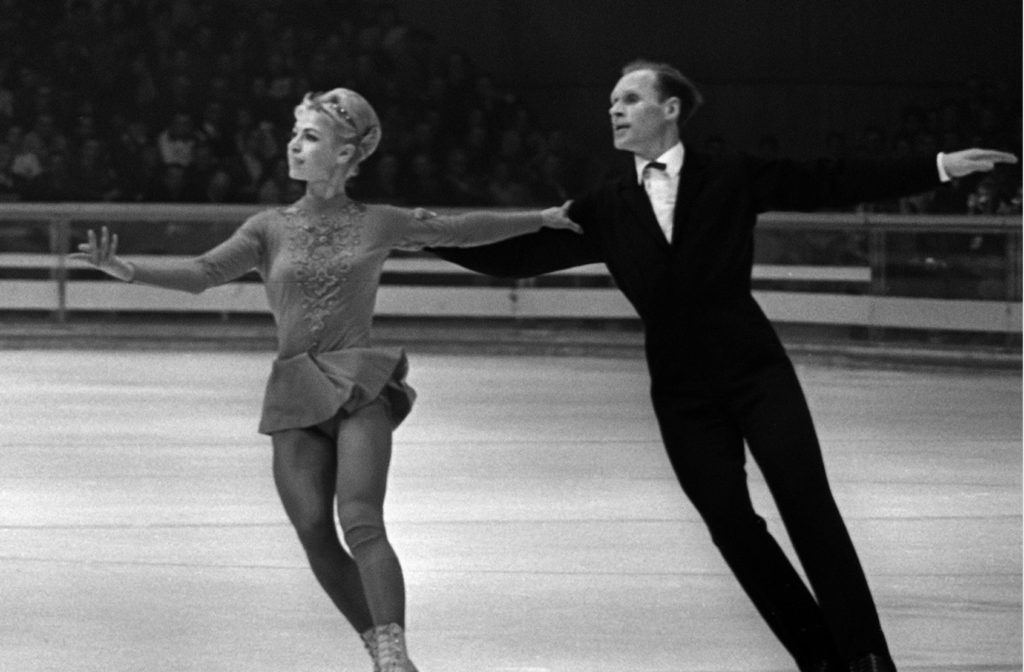

We know how long skating has been the preserve of the Soviets, particularly in pairs (people of my generation remember Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov), who also used it as an instrument of ‘soft power’.

The world of the surface (from above) is precisely a world of superficial glossy images, serving the image of an ideal, just as figure skating couples display the image of the ideal couple, regardless of what lies behind the image and the free or compulsory figures, the suffering and the struggles against their own nature. Displaying the heterosexual skating couple is a metaphor for the good health of a society that produces children, where moral order reigns, and thus shows that we are powerful, great, and rich in future prospects. Quite a programme to dream about…

This metaphor raises exactly the question that the directors ask in the work : behind the smile and the glossy happiness of the fairy tale, what is the truth ?

This is why they make Ludmila a figure of liberation who will live her life “underground”, a truly subterranean life, but they also reflect on Ruslan, taking advantage of the hero's procrastination in the original tale, where he forgets Ludmila and finds his friend Ratmir. The search for Ludmila becomes both a nightmare and a search for self, in the recesses of the soul, in hidden corners, that is to say, ‘underneath’. The underground is not only the underside of society, but also the underside of somewhat lost souls.

Fairy tales and wonderful stories always place obstacles in the path of heroes, temptations that they cannot resist at first : fairy tales and epics are full of such stories, which we find in the theatre if we think of Shakespeare (A Midsummer Night's Dream) or, again and again, Wagner, whose contribution to the wonderful world of fairy tales cannot be overestimated : Siegfried's potion of forgetfulness in Götterdämmerung, what else is it but Alcina's magical stratagem to divert the hero from his mission…

Ruslan is the one who is diverted, or more subtly, who ‘diverts’ himself, and who, thanks to this diversion, also understands that his desires are not as clear-cut as one might have thought… For Alexandra Szemerédy and Magdolna Parditka, he is the one who has suppressed his homosexuality and his love for Ratmir in order to marry Ludmila, out of a desire to conform to social norms in the world above… This is made very clear at the outset : before the wedding, Ruslan is alone with a glass of alcohol, visibly uncomfortable, and Ludmila is in no better position on her skates… The happy marriage is not really happy.

What does this mean in the underworld ?

Let's be clear : the two directors' analysis does not consist of imposing contemporary ideas on a fairy tale from 1820, forcing in ideas that are not there. On the contrary, they take advantage of the density of the story, the various adventures, the twists and turns, and even the hesitations of the characters who, in the course of the story, forget (magic or not?) their duty or mission, to slip in possibilities, to show behind the tale another story in the mirror, which is not exactly what we expect, and they are quite convincing in this endeavour.

Any viewer who has never seen their work understands from the very first images that they are true directors, that they know what theatre means, even if here and there one can discuss their vision, which is quite banal in the sense of today's society, and which could be accused of replacing one order with another, which some also accuse of being totalitarian… In my opinion, it is not the density of ideas that should be praised here, which are in line with a certain trend, but rather the way in which they are presented.

Thus, the castle of Naïna has become a queer nightclub ‘in the underground’ that attracts everything that moves and wants to enjoy itself without restraint, and everything that is not exactly within the norm, a temple of pleasures that are permitted in the underworld but forbidden in the upper world. Next door are a few shops, including a bridal gown shop that fascinates Ratmir to the point of dressing up and finding his true nature. The decision to cast Ratmir as a countertenor instead of the planned contralto is also an interesting choice in this regard, as it accentuates the ambiguities and gender games.

Those who accuse Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy of steering the story towards what it does not say, of transforming the fairy tale, of reversing the facts, are seriously mistaken. In reality, they are simply continuing a tradition that began in the 19th century and is quite widespread. We have mentioned the magical worlds of Klingsor, worlds that are certainly viewed negatively from the vaguely Christian perspective of Parsifal, but we could just as easily and still within Wagner's work, evoke the Venusberg cave in Tannhäuser, a kind of anticipation of the infernal world, but a paradoxical infernal world of all pleasures, which is well worth the sclerotic world of the Wartburg : Kratzer himself had shown this in Bayreuth, and before him Baumgarten, with less skill (the ballet of the spermatozoa, one of the unforgettable highlights of the Bayreuth Festival…) and in another vein, by stretching the myth of Orpheus to the point of distortion, Offenbach made Hell in his Orphée aux Enfers a world of pleasures from which Eurydice has no desire to escape. Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy merely extend this idea, which Offenbach the transgressor had already explored and which Tannhäuser celebrates in his song about the Venusberg.

Hell isn't so bad : it's even the subject of some of the most influential works of world literature, thanks to Dante.

They also show the limits of ‘licence’ insofar as this underground world, this subterranean world where everything happens, is soon controlled by the forces of law and order, who shut it down with batons. The order of the upper world also ends up reigning in the underworld. The underground world need only exist to disturb the world above, to frighten it : fear is the driving force behind the regimes of the world above… It is indeed the question of imposed social norms, of societies of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ established by decree or by George Bush or Donald Trump, or even Vladimir Putin, well-known moral models, that is denounced here : the fairy tale has literary value, but also educational and prescriptive value : Little Red Riding Hood must not under any circumstances see the wolf…

Obviously, this visual translation is first and foremost a symbolic translation, ‘hidden vices, public virtues’; the world is appearance, and being is not always where we think it is. But perhaps we should also reverse vice and virtue, insofar as Alexandra Szemerédy and Magdolna Parditka try to show characters who go to the limits of their freedom, or rather their liberation. Is virtue really to be found in Ludmila, who suffers in order to obey her father, a skating coach ? Or even in Ludmila, who is forced to wait for Prince Charming ?

They very effectively raise questions about the relativity of the world, points of view, personal demands and dreams that do not conform to the norm.

Because ultimately, the question is always the same : how does my freedom to be who I am clash with the world order ? In no way, of course, unless we decide that the world order is that demanded by imposed norms that restrain individuals who do not comply with them, unless we decide that the only freedom is that of adhering volens nolens to the imposed order, the order of DJ Vance, Putin or Orban. The underground world, because it is underground, should not bother anyone, but the violent (in ‘slow motion’) intervention of the police in the staging shows that its very existence is disturbing because it is a threat. The exercise of freedom, however minimal, is always a threat to those in power.

Pushkin's fairy tale returns to order at the end… we saw Ludmila asleep on stage, trying to commit suicide with the blade of her skates while singing her grand aria from the fourth act, a sublime moment accompanied on stage by Konradin Seitzer's violin : is freedom to the point of self-destruction acceptable ? Does society have a duty to save its lost souls, or those who wish to lose themselves ? For what ultimate order ?

We have seen how the ending of Ruslan and Ludmila conforms to the order of the world (that of the father), and the libretto itself highlights the instabilities of the characters, who eventually get back on the right track : Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy emphasise all these ambiguities by making the ending the end of a nightmare : it begins with a wedding ceremony that is in fact Ludmila's funeral in her coffin, but soon the dead Ludmila awakens and briefly returns to the wedding, this time without soldiers to keep everything in order, but this ending cannot be an orderly and conventional one ; it is an ending that could have been but will not be. As the highly biased summary of the plot in the programme booklet says : Return to the initial ballroom. Ljudmila and the others are back home. Nothing stands in the way of the wedding. Or does it ?

The final question mark obviously leaves a doubt that is not really a doubt, and it is an interesting twist to leave everyone in limbo. Our questions are left unanswered, our answers are left unanswered, the world and its moral order, which is not really an order, which is never an order, are left unanswered, uncertain too is the world on the other side or underneath, where Banksy's graffiti will become negotiable ‘values’ in the world ‘above’… Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy show us for a moment the world in which we live, as uncultivated as our souls : they know that we never stop believing in fairy tales (the internet is full of them, influencers sell them to us galore, etc.) so, in the end, instead of returning to the old order as planned in the libretto, it all ends in a queer celebration with rainbow flags, where everyone finally finds their way. Is this the real ending, the dream ending where everyone is free and happy ? Not so sure, but let's pretend to believe it.

Thus, this eminently theatrical work (well lit by Bernd Gallasch's lights) proves to go quite beyond the world of conformity that is on display and the hidden world that rejects it : Magdolna Parditka and Alexandra Szemerédy show that it is impossible today to cling to any system of values whatsoever. They reveal the presence of threats through a story by Pushkin, who, like Victor Hugo, is a ‘formidable observer’ of the world. In this show, they display a true vision. This is rare enough in theatre to be worth mentioning. We therefore eagerly await their future Rienzi…

The musical aspects

Serving this vision is a particularly musically accomplished ensemble, which, it should be noted, does not include any world-famous names from the opera pantheon, but rather solid artists, both from the troupe and guest performers, who defend both the work and the staging with genuine commitment.

One cannot consider the highly successful musical aspects of this evening without first mentioning this astonishing music, of which we, like everyone else, knew only the overture, and which reveals itself to be an incredible melting pot of everything that the 19th century produced and would produce, in Russia and elsewhere. If Liszt and Berlioz loved this music, there must be a reason !

Glinka was a very keen observer of the music of his time. In 1842, the great era of bel canto was coming to an end, but it was still the time of Grand Opera. We therefore find a vocal style, particularly for Ludmila, that brings her closer to the great bel canto heroines, notably in her aria in the fourth act, which is a firework display of sustained notes, high notes, agility and inner singing.

But we also find many of the characteristics of Grand Opera, first of all the five-act structure, then also the fairly traditional presence in grand opera of a travesti role, Ratmir, entrusted to a contralto. One need only think of Urbain in Les Huguenots, Jemmy in Guillaume Tell, Adriano in Rienzi or Ascanio in Berlioz's Benvenuto Cellini, but also Oscar in Verdi's Ballo in Maschera and Siebel in Gounod's Faust are recent examples.

Another peculiarity, in a different direction, is that the only tenor is Bayan/Finn, but this is not the leading role and the hero is a baritone, with baritones and basses sharing most of the vocal cake (Farlaf, Svetosar, Rouslan), opening up the tradition of Russian voices with their abyssal depths…

But if we hear Donizetti, whom Glinka knew, if we hear a little Meyerbeer, we also hear echoes of Russian folk music, and musical phrases that we will hear again in Borodin or Rimsky-Korsakov (The Golden Cockerel…) and ballet music (part of which has been cut here) that seems to have been written by the future Tchaikovsky.

This is not to say that they all plundered Glinka, but that listening to his music, we understand the paths he opened up for the future of Russian music, but also how open the musical world of the time was, and how much everything circulated : the colour of Donizetti, more than Bellini, is also very much present. To create a work is to draw on existing material and make something new out of it. To be honest, one wonders why Ruslan and Ludmila is not performed more often in our part of the world : it is a great work, worth much more than all the Fedoras in the world…

As always in Hamburg, the local troupe takes its share of the roles, starting with Kristina Stanek as Naina, with her beautiful mezzo voice that we have enjoyed elsewhere (she is a magnificent Eboli): the role is episodic, but sufficiently present for us to hear her well-placed, controlled and powerful voice.

Natalia Tanasii is a young Moldovan soprano who sings Gorislava with a beautiful, rich, clear voice, well-projected high notes and a striking stage presence in the queer bar scene. Very interesting artist to watch in the future.

Alexander Roslavets, a member of the Hamburg troupe since 2016, is Svetosar. He needs no introduction, as he is so well known in Hamburg and elsewhere for his major bass roles ; for example, he was Boris in Toulouse in 2023, and we have seen him outside Hamburg in War and Peace in both Munich (Tcherniakov production) and Geneva (Bieito production). Here he is Svetosar, a ‘noble’ father " with a deep, sonorous voice that is particularly imposing.

The young Alexei Botnarciuc, who like Natalia Tanasii comes from Moldova, is a rather rough-and-ready Farlaf, which is the character he needs to be opposite the more ‘refined’ Ratmir… there is obviously a range of characters to be respected, each corresponding to a vocal range. His voice is therefore truly granite-like, quite impressive.

Artem Krutko is Ratmir, in a role usually given to a contralto. He performs the task with supreme vocal elegance, demonstrating solidity across the entire spectrum ; he is even quite impressive at times. In addition to his outstanding qualities, technique, projection, colour, sense of irony and sensitivity, he adds a particularly strong stage presence, portraying a real character, ambiguous, sometimes lost, who is searching for himself and ultimately finds himself in his relationship with Ruslan ; absolutely remarkable.

The highly refined Nicky Spence is Bayan and Finn – the staging merges them – and he uses his melancholic, supremely controlled voice as a guide, a gentle and delicate ringmaster, throughout the opera. His aria in the first act has been moved to the last to mark a more tender tone, contrasting with the final explosions. The directors have given him a vague clownish appearance that suits his clear, precise, technically impeccable voice, nourished by the baroque and bel canto repertoires.

Ruslan is Ilia Kazakov. This baritone with a warm, elegant voice was previously a member of the Vienna State Opera and has just joined the Hamburg Opera. He is a committed Ruslan, quite far from the handsome white knight and the charming prince who is self-confident and domineering because he is handsome and blond. He shows his doubts from the very first image. He is initially a lost character, somewhat carried along by circumstances and the staging, and he revolves more around himself (journey inside my self…, in ‘my underworld’) than around Ludmila, who does not appear in the second and third acts. This Ruslan discovers himself to be different from what he was or how he presented himself, and Ilia Kazakov makes him a character who is both tormented and profound, with a very lyrical, powerful voice that adapts to the different colours of the character with particular flexibility. The beauty of his timbre, his projection, and vocal and stage commitment make him a truly exceptional Ruslan who wins a well-deserved resounding success.

Finally, Barno Ismatullaeva is an almost ideal Ludmila. She possesses impressive technical assurance for a formidable role, with strong bel canto colours and all the characteristics one would expect : lyricism, intensity, depth and embodiment, but with completely mastered coloratura and also more raw accents of truth combined with a real stage presence, particularly in the fourth act, where she is particularly captivating. She has successfully performed Elisabetta in Maria Stuarda on this same stage, and will soon be Butterfly. A soprano of this quality, with such a pure voice, is undoubtedly one to watch.

The Hamburg State Opera chorus, prepared by Alice Meregaglia, showed real power in each of its relatively numerous appearances and gave a very respectable performance overall, but it was the orchestra, the Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg, which was truly surprising, conducted with vigour and power by Azim Karimov, an ex-student and assistant to Vladimir Jurowski, who demonstrated here that he has all the qualities of a true opera conductor. First, the overture was a celebration of colour and energy ; then he accompanied the voices without ever drowning them out, giving the orchestral moments a special relief and, above all, highlighting the orchestra's sections, particularly the woodwinds, which play an essential role (English horn, clarinet) and lend the ensemble a certain introspection and melancholy. The interest of his conducting lies in the fact that he seamlessly embraces all styles, sometimes Rossinian or Donizettian, sometimes more idiomatically Russian, without any breaks, with a kind of logic and depth that delves into every corner of the score to bring out an explosion of diverse colours and youthful energy at times and chiaroscuro at others. We knew that Karimov showed great promise, and he confirms that he is a force to be reckoned with, and probably not only in the Russian repertoire. Yet another Russian conductor (in exile) to add to the range of precise, intelligent and sensitive conductors available today, who know how to “make music” and not just “conduct an opera”.

All in all, a powerful evening, a complex but intelligent and successful show, and a remarkable musical performance… You have until 19 December to see for yourself…