Contexts

At the heart of this production is the personality of Heiner Müller (who died in 1995), who, like Castorf, came from the former GDR and was a key figure in the German intellectual world of the late 20th century. He was a writer, playwright, poet and stage-director (Tristan und Isolde in Bayreuth in 1993) and is referenced here both as a translator of Shakespeare and as the author of Die Hamletmaschine, the short play (9 pages) he wrote in 1977, banned by the regime and premiered in France in 1979 at the Théâtre Gérard Philipe in Saint Denis, directed by Jean Jourdheuil with sets by Gilles Aillaud.

All of Castorf's work plunges us into the depths of history, and in this production of Hamlet, which essentially covers the first three acts of the original, minus the last two, history is ever-present, explaining the dystopia experienced on stage, a dystopia that Aleksandar Denić's set design starkly exposes.

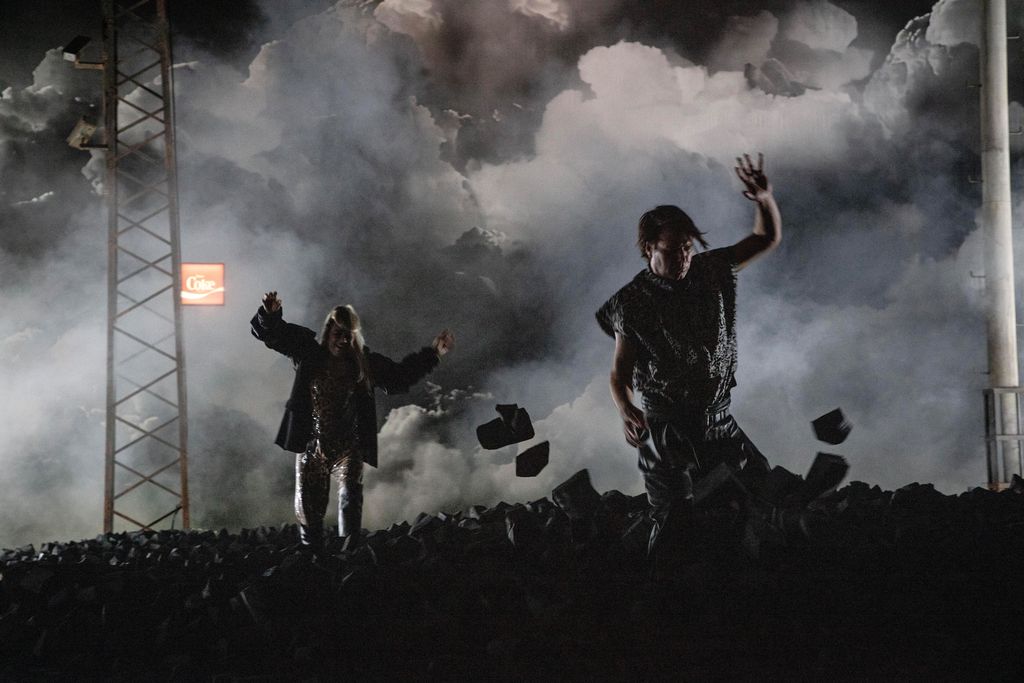

Under Lothar Baumgarte's sublime lighting, stretched between an electricity pole and a pylon, against a backdrop of threatening clouds, we can make out the word ‘Europe’ upside down, with the E already almost fallen off, like the entrance to a ruined Disneyland, of which all that remains is a concrete bunker and a pile of coal rubble into which the actors delightedly plunge as if into a five-star hotel swimming pool. Enjoyment amid ruin.

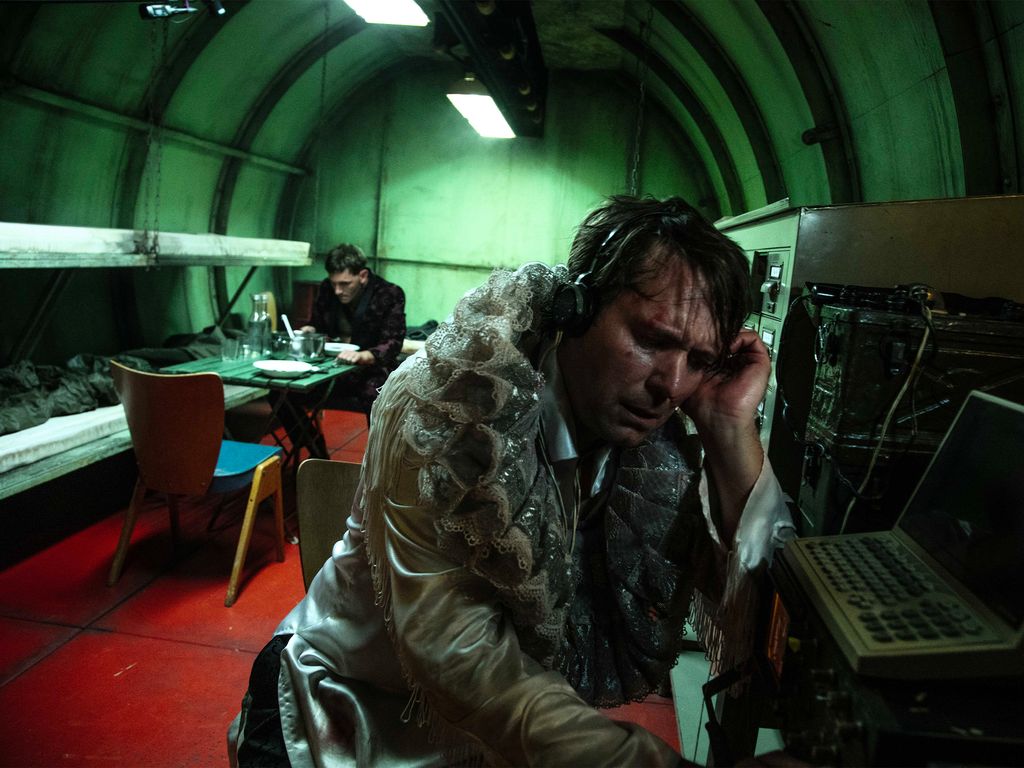

The set will change slightly, mainly in the second half, but much of the action takes place offstage with live cameras, behind the scenes or below ground, in a shelter accessed via the bunker, a tiled storage room filled with stained mattresses, files, and other relics that will be used from time to time, which Aleksandar Denić turns into a masterpiece of trashy precision. Many scenes, including the famous ‘to be or not to be’ scene, take place in this location, which we only see on video and which ends up suffocating the audience.

It is obvious to everyone that we are in an aftermath, in the aftermath described by Heiner Müller's first words in his Hamletmaschine :

"I was Hamlet. I stood on the shore and spoke with the surf BLABLA, behind me the ruins of Europe. "

And Castorf refuses to update the situation : the devastation observed by Heiner Müller in 1977 is the very landscape of 2025. Frank Castorf is also the one who, from production to production, persists and signs, that is to say – much to the chagrin of his detractors – denounces the misdeeds of ideologies during the Cold War and in particular Marxist illusions, while also showing that imperialism takes many forms, which he summarises by the permanent presence in all of Aleksandar Denić's sets of a ‘Coca-Cola’ (here “Coke”) advert, judiciously placed under the word ‘Europe’ written backwards. He thus shows that where there is ruin, there is always Coca-Cola to console us, which resists all adversity…

Moreover, towards the end of the performance, when all the actors are confined to the stifling underground shelter (we are also aware of Castorf's radical positions during lockdown and the pandemic), one of the actresses gorges herself on Coca-Cola, taken from the shelter's reserves (the universal sustenance, in short), which foams like champagne when opened.

All is lost except Coca-Cola…

Hamlet : the unanswered question

I can imagine the reader grimacing and wondering… ‘What does Hamlet have to do with all this?’

That brings us to the heart of the matter. Hamlet is the tragedy of a resolution that is not a resolution, with only one certainty : the murder of Hamlet's father by his brother Claudius, who then married his mother, Gertrude. One is struck by the similarity with the story of the Atreides, Aegisthus and Clytemnestra murdering Agamemnon on the day of his return from Troy for having unleashed war by sacrificing Iphigenia. Hamlet is here the equivalent of a vengeful Electra.

Hamlet's tragedy is a bloodbath ; all the main characters die, first Polonius, father of Ophelia, Hamlet's lover, who drowns herself in a stream, then in the final moments Claudius, the usurping uncle, Gertrude, his wife and Hamlet's mother, but also Laertes, Ophelia's brother, who dies with Hamlet in single combat, with some collateral damage including the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Hamlet's courtiers and friends, all against the backdrop of a European war between Fortinbras, nephew of the King of Norway, whom Hamlet designates as his heir, and Denmark first, and Poland second… We end up wondering why this massacre, what justifies this disaster, where is the truth ? Where is justice ?

Hamlet was published at the end of Elizabeth I's reign, at a time of turmoil when the question of her succession was being raised, a leap into the unknown, but for Shakespeare too, things were becoming tense : his father died, his patron was beheaded by the queen, and his son had died a few years earlier – his name was Hamnet (a recent film by Chloé Zhao tells this story).

The turmoil is therefore shared at all levels : there is the question of madness : to what extent is Hamlet feigning madness ? Is he mad ? Where is the truth and where is the falsehood ? Where is the being and where is the appearance ? These are questions to which the text does not really answer, and whose only truth is a kind of universal disaster.

At the heart of the work is the question of theatre, addressed by Shakespeare with the scene of the actors playing out the murder of Hamlet's father (they have the same name) to reveal the crime through the reaction of the criminal couple (a double crime, since marrying Claudius was also considered incest at the time): truth comes from theatre… But what is theatrical truth ? Who is acting ? Where is the character and where is the actor ? Where does the illusion lie ? These are questions that all Baroque theatre asks itself and which Castorf never ceases to play with.

Castorf and Hamlet

Heiner Müller, in his Hamletmaschine, which opens with ‘I was Hamlet’, raises the question of the actor and the doubling, and this is a question that runs through the entire performance, even to the point of self-mockery when the actor Matti Krause imitates Frank Castorf (quoting him) giving stage directions and provoking laughter in the audience. More broadly, the show constantly raises the question of theatre as a vehicle, as the sole vehicle of truth/reality, which is a baroque issue fully embraced in Shakespeare's Hamlet and in much of 17th-century theatre production, whether by Tirso de Molina or even Corneille, when we think in particular of L'Illusion Comique.

There is something in this production of L'Illusion Comique, where the ‘performance’ of Hamlet coexists with his plunge into the auditorium, breaking the fourth wall when Hamlet pursues Ophelia among the rows of spectators in the stalls, shouting "Entschuldigung, entschuldigung ' (Excuse me, excuse me), we wonder whether this word is in the text or strictly performative, insofar as, as he crosses the aisles, he forces people to stand up or turn around to let him pass. Where, then, is the theatre ?

The same ‘theatrical’ ambiguity arises at the end of the first part, when, after three incredibly intense hours, all the spectators think it is the interval and rush outside to stretch their legs, and the ‘real’ stage manager (responsible for ensuring that the evening runs smoothly), Olaf Rausch, brings Hamlet a sandwich so that he can take a breather and eat something… To Hamlet or to Paul Behren the actor…?

And the scene, effectively interrupted by this smile at the end of the first part, is repeated at the beginning of the second part, this time more theatrically, since the interval is over and Hamlet/Behren, ready for new adventures in a shiny new costume, is once again served a sandwich by Olaf Rausch, stage manager… and actor (as he appears in the cast list, and in the ‘actors’ column, and in the ‘technicians’ column).

Ambiguity reigns from the outset, which begins with Heiner Müller's words ‘I was Hamlet…’ from Hamletmaschine, and the actor who appears to be playing Hamlet (Jonathan Kempf) is not actually Hamlet, but Heiner Müller's split Hamlet. The play on the illusions of being and appearance thus begins when the curtain rises and the audience discovers the ‘Müllerian’ set designed by Aleksandar Denić and begins to grope its way through the maelstrom.

This back-and-forth between being and appearance, theatrical illusion and reality, which is one of the characteristics of the Baroque, is one of the main themes of the show, giving this Hamlet and Frank Castorf's interpretation of it the character of a great Baroque performance. The costumes of the ‘actors’ " (as Hamlet calls them in the play to confuse Claudius) are clearly reminiscent of baroque ballet costumes, with their sequins, glitter, shapes and sometimes astonishing headdresses.

The costumes by Adriana Braga Peretzki, who always draws inspiration from the carnival costumes of her native Brazil, are incredibly elaborate, with feather headdresses (Inca), or sun hats, sequined leotards, feathered accessories, but also brightly coloured suits (purple, apple green) or shirts that reveal the body beneath the embroidery or lace.

Not to mention Claudius's incredible headdress in the second part, which resembles a structure by the sculptor César, or the compressed rubbish that is about to be burned, made up of tin cans, plastic bottles and cans (of Coca-Cola, among other things), turning Claudius (the magnificent Josef Ostendorf) into a kind of element of this compression, rubbish topped with rubbish, or at the end of the play Gertrude (Angelika Richter) in a jellyfish costume, a poisonous jellyfish (Gertrude, who ends up poisoned).

Other fleeting elements border on the gag, such as the name of Josef Ostendorf, the actor who plays Claudius, written on a seat in the corner of the stage (like in cinema seats), which is angrily removed to be used in the play, or Ostendorf himself backstage, changing costumes and joking with the technical staff present.

As the performance progresses, the question of theatre and the relationship between spectator and performance, actor and character, set and wings is raised, either fleetingly or insistently, in the form of a gag or otherwise : we are in the theatre, and theatre has a function that is sometimes cathartic (allusions to Greek tragedy and Heiner Müller's texts on myths), such as Prometheus bringing fire to mankind, played and spoken by an incredible Matti Krause straddling one of the bunker's slit windows, between which Gertrude (Angelika Richter) manages to slip through to applause at the end of the show), and sometimes didactic (allusions to Brecht), including in the form of a reality/illusion game when Hamlet calls out to the actor Matti Krause (him again…).

on his first name (‘Matti’), an allusion to Brecht's play (Mr Puntila And His Man Matti) or draws on Artaud's theatre of cruelty, with its abundance of blood : in the background is a refrigerator that is opened, filled with blood, which Ophelia (Lilith Stangenberg) covers herself with

or by the presence of Artaud's texts on theatre and the plague, a sort of motto for Castorf, illuminated by a powerful text recited at the end of the performance by Angelika Richter. I wrote about this in my review of his production of Racine’s Bajazet in 2019 :

For although Theatre and the Plague is part of the title of the show, the text itself is not quoted : the title was also the subtitle of his Life of Galileo (Berliner Ensemble, 2018–2019 season): theatre serves to reveal the truths of the world and throw them back in the face of the spectator, the plague settling in a body that it circumvents, just as theatre must settle in the body of the spectator and make them see life with different eyes : what is plague in theatre is that it is the necessary disease of man. A director like Castorf believes in the revealing, provocative and confrontational value of theatre and therefore in its aggressive value, like the plague, revealing our guts, our pustules, our pus, our sufferings, our contradictions, our end.

Admittedly, Castorf never deviates from his established certainties and each production is also a variation on a widely known and developed discourse. But Hamlet lends itself particularly well to this, with its hazy meaning : Hamlet uses theatre as a revealer of humanity and its turpitudes through the actors performances, but at the same time questions the reality of the world, the true and the false, which are such pressing questions today with the dangers of “fake news” and AI, but also the violence that pervades it. Castorf turns all this into a huge revue, in the sense of the term used by the Paris Folies Bergère. At the Folies Bergère, they presented a revue with a promising and touristy title such as ‘That's Paris ! ’; in Castorf's work, the revue could be called ‘That's the World !’, with its dystopian, wild, contradictory result, with its shocks, its lengths, its stunning beauty, its emotions and its annoyances : that's Castorf, and it's take it or leave it.

So, as always, this is not theatre but hyper-theatre, as we say hypertext, a theatre with multiple links, a theatre where video plays a central role, showing what we see on stage from another angle, in close-ups of certain faces until they become monstrous and lose all trace of humanity, or from afar, from the heights of the theatre, to embrace the character, the stage and the setting, and also in pure video broadcast from below with acrobatic cameras (Andreas Deinert and Jens Crull as usual, but also Severin Ranke, Björn Gallus and Maryvonne Riedelsheimer): in this respect, the first descent into the underground shelter, with the two actors (Lilith Stangenberg, Daniel Hoevels) clinging to the ladder in all directions as if in a gruelling but accepted descent into Hell, in impossible monologues, is one of the most powerful moments of the evening because this live video becomes a theatre of the impossible.

The fallout shelter is the second setting (invisible to the naked eye), typical for its precision and design from the imagination of Aleksandar Denić. The idea is obviously to make this space a kind of ultimate living space, with all its details and requirements : people cook there, sleep on makeshift beds and filthy mattresses, writing, listening to the world with a kind of old spy device, as if in a submarine looking out at the open air, and finding a series of metal files containing cardboard index cards (remnants of the Stasi files, with one of the characters uttering the famous pun, ‘Everything is Stasi, except Mutti’). (Mutti = mum), like a kind of old clandestine spy hideout (in Hamlet, everyone mistrusts everyone else and so they all spy on each other a little), which has become a shelter (on the wall is a guide showing how to escape nuclear danger), and it is in this impossible and suffocating place, sitting on a bed, Hamlet delivers his famous, highly symbolic ‘to be or not to be’ monologue, while Ophelia tries to distract him with her coquettish behaviour. It is also in this place, or non-place, that we see one of Hamlet's only gestures of tenderness towards Ophelia, as he gives her a spoonful of vegetable soup (the vegetables are clearly visible), which gives the unpleasant impression of a meal being served to prisoners. This vision obviously evokes both the end of a world, somewhat reminiscent of Tcherniakov's idea in his Salzburg Giulio Cesare, and the idea of a confined, almost concentration camp-like universe, in other words, we are presented with a humanity in the process of decay, with a few glimmers of rebellion when they tear down the “Stasi” files and empty the metal cabinet with all the cardboard files on the floor, but the rebellion against the Stasi is “post-mortem”, the files are on the ground, but they are only relics : the gesture is empty, hollow, useless. In all these long, underground scenes, there is a kind of double ordeal for both the actors and the audience : pure theatre of cruelty for all.

A theatre of Dionysian destabilisation

It is important to reiterate the complete consistency with the world of Hamlet, a hero who gradually sees the ground slipping away beneath him and who is constantly confronted with the question of appearance versus reality, truth versus falsehood, in all areas of human activity and in a context of collapse.

It should be remembered that the birth of the Baroque period stemmed from the profound sense of instability that gripped humanity at the end of the 16th century, which was plagued by upheavals of all kinds : the crisis of Christianity throughout the 16th century, the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, but also (and Shakespeare was at the forefront of this) the separation of the Anglican Church since Henry VIII, of whom Elizabeth I was the daughter, and therefore profound religious instability. Furthermore, the universe was changing in size. Until then, it had been thought that man and the earth were at the centre, but Copernicus showed that the earth revolves around the sun, which destabilised all the scientific certainties of the time, which were also confirmed by religious beliefs based on Aristotle. In 1609, a few years before Shakespeare's death in 1616, Galileo developed the astronomical telescope, revolutionising the observation of the universe and confirming Copernicus's theory. This change in the position of man in relation to the universe was a shock not only scientifically and philosophically, but also religiously, and it almost cost Galileo his life, and did cost Giordano Bruno his in 1600 (precisely in the years when Hamlet was written). Castorf has already dealt with Galileo in his 2019 production of Galileo Galilei (The Life of Galileo) based on Brecht at the Berliner Ensemble, once again putting Brecht and Artaud into perspective (The Theatre and the Plague).

This destabilisation is a sign that can be found politically throughout Europe, with the succession of Elizabeth I and the accession to the throne of James I, son of Mary Stuart, the assassination of Henry IV in 1610 in France, with a turbulent regency (Marie de Médicis and Concino Concini, executed in 1617), which only stabilised with the arrival of Richelieu in power after 1624. As for Spain, in the years when Shakespeare was writing Hamlet, Philip II died and his son Philip III (who died in 1621) left all power to his favourites.

As we can see, disintegration and instability reigned at the beginning of the 17th century, and Hamlet must be read in this context. Thus, we understand that reading Shakespeare's text through the prism of post-war European tragedies, as Heiner Müller does, and through the prism of our own instability, as Castorf suggests here, is not a misinterpretation. Literature and theatre explain the world, whatever that world may be, and this is also what Artaud's text says when he compares theatre to the plague, like an epidemic :

"(…) and we can see, in the end, that from a human point of view, the action of theatre, like that of the plague, is beneficial, because by pushing people to see themselves as they are, it removes the mask, it reveals the lies, the cowardice, the baseness, the hypocrisy ; it shakes off the suffocating inertia of matter that pervades even the clearest data of the senses ; and by revealing to communities their dark power, their hidden strength, it invites them to take a heroic and superior attitude towards destiny that they would never have had otherwise. And the question that now arises is whether, in this world that is slipping away, committing suicide without realising it, there will be a core of people capable of imposing this superior notion of theatre, which will give us all back the natural and magical equivalent of the dogmas we no longer believe in.

Thus, this Hamlet is a journey of “travelling players”, in the sense of Theo Angelopoulos' film, Ο Θίασος (O thiasos, meaning the troupe of actors), which in ancient times referred to the troupe that surrounded Dionysus (the satyrs and maenads).

There is indeed a Dionysian vitality and a kind of frenzied energy of despair in a landscape that is falling apart, that is nothing but traces, traces of Europe, with its somewhat crippled name, traces of ruins, with the coal that covers the stage, coal that itself is born from the decomposition of organic matter : it is indeed decomposing organic matter that is shown to us here. The blood from the fridge mentioned earlier is itself drying up, and the bunker is an entrance to a fallout shelter, itself in a sorry state, like a kind of last place to live, while in the open air the world is destroying itself and becoming fossilised

The famous monologue ‘To be or not to be’ is delivered without enthusiasm or emphasis, as if to deny the ‘theatrical momentum’ by Hamlet sitting on a bed behind which posters indicate how to descend into a nuclear shelter in the event of an attack… To be or not to be and the elements of survival are as diverse as life itself : a former Stasi file, bottles of Coca-Cola, vegetable soup that Hamlet serves to Ophelia in a rare gesture of love, as we have seen, a chess set with all its cultural and symbolic significance (checkmate), and basic, intermittent communication tools, like a shortcut to the world in which all the actors will end up locked up at the end. There is a prison space, a Sartrian No Exit (Huis clos), a figure of Hell, and the fact that it is underground makes it the perfect metaphor.

Opposite this Hell, a large, closed and suffocating tube, a kind of antithetical figure appears on stage, a luminous vortex, a neon tunnel that could easily be seen in a television game show, which projects into a kind of totally unreal world opposite the hyperrealism of the basement, in which Claudius, Gertrude, Hamlet, watch the actors in the baroque costumes mentioned above : it is at this moment that Claudius, in a wheelchair, is decked out in this impossible headdress made of all the filth of our civilisation. There is a kind of permanent explosion of the world between the visible and the invisible, between the stage and the wings, between the real and the fake, between the represented and the representation of the represented, a kind of frenzied whirlwind that is in fact a metaphor for Hamlet's soul, which is everything and its opposite.

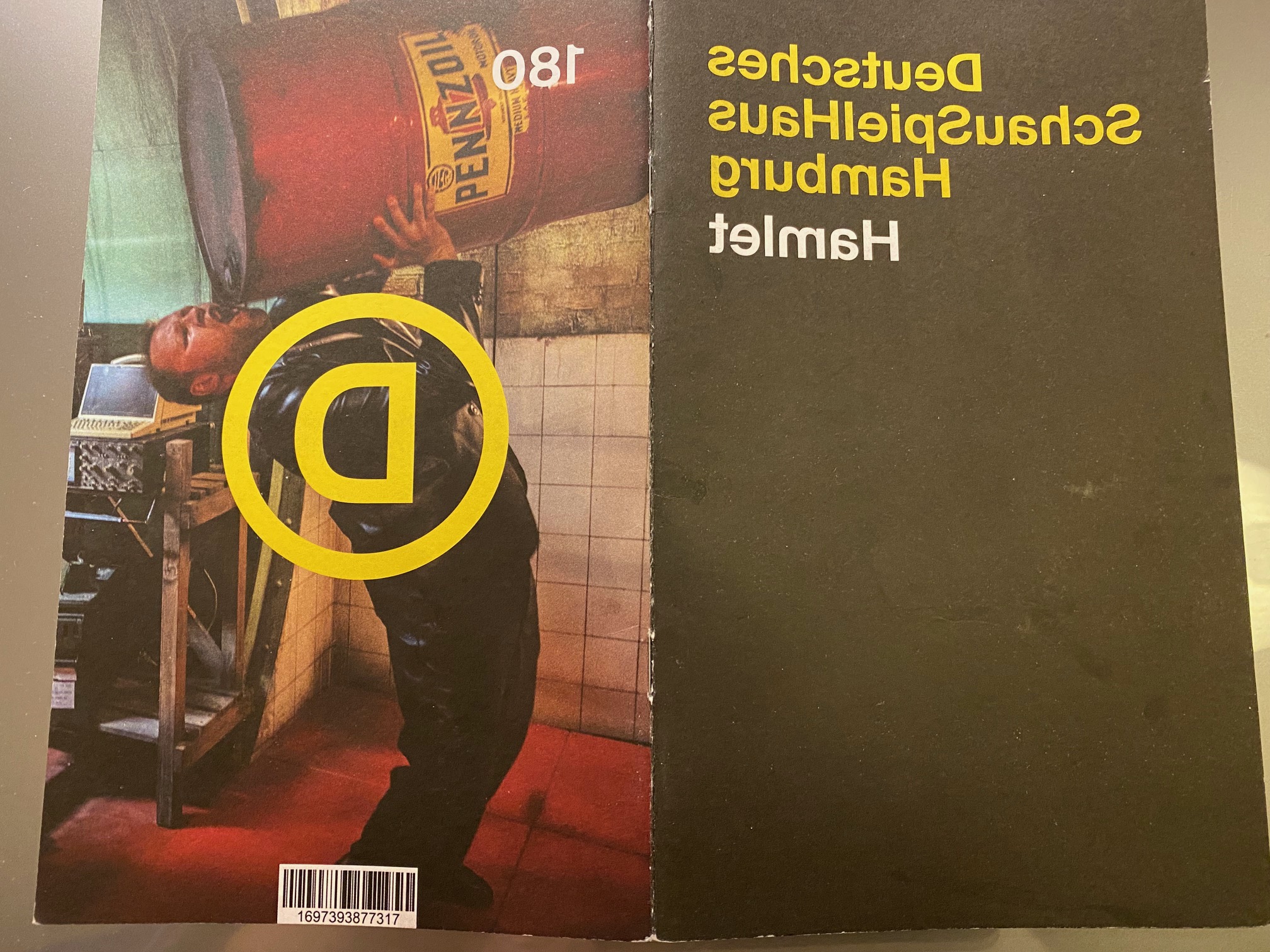

And in this upside-down world, we understand why the programme prints the title ‘backwards’, as shown in our photo. It is a question of reading a world that has lost its meaning and direction. To rediscover the intended meaning, one simply has to read the title in a mirror, in a reflection, the real in the mirror, the real in the reflection… yet another baroque game.

We could multiply ad infinitum the discoveries, the moments of trial, which seem endless, and which Castorf plays on, to prolong the cruel torment of Artaud's theatre on our own skin, the unbearable cries, the noises, the raucous breathing, but also the moments of emotion, such as that almost initial moment when Heiner Müller's Hamlet (Jonathan Kempf) and Shakespeare's Hamlet (Paul Behren) dance together, the one who was Hamlet and the one who will be, or who is… an ineffable moment of suspended theatre, or the more acrobatic moments, with Matti Krause absolutely extraordinary, straddling one of the cracks in the Bunker, imperturbably continuing his Promethean monologue (already mentioned above), Josef Ostendorf's kaleidoscopic Claudius, from king to clown, from paternal uncle to king clinging to his power, with a voice that retains a reassuring softness and sweetness, and those fleeting moments when authoritarianism, lies and duplicity emerge at the turn of an inflection. But at the same time, he rules the world by wanting to transform it, clean it up, at the wheel of a small digger that tries in vain to stir up the coal, like a warm-up lap at the bottom with no effect whatsoever.

Daniel Hoevels is also extraordinary, turning his voice into a beastly instrument during a monologue that is almost unbearable, repetitive, where sentences are followed by animalistic, inhuman cries, across an incredibly diverse sound spectrum or monologuing to the point of madness, stuck on the ladder that leads him to safety.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are played by Alberta von Pöllnitz and Linn Reusse, who also play among the actors Hamlet pays to circumvent Claudius, members of the all-purpose troupe, where women play men (in Shakespeare's time it was the other way around)…

Angelika Richter (Gertrude) is also incredibly intense, particularly in her almost final monologue on Theatre and the Plague : one doesn't know what to admire, the diction, the clarity, the modulation, the multiple inflections, which never cease to fascinate almost ‘aesthetically’ before gripping the audience and moving them deeply.

Lilith Stangenberg's distraught Ophelia is also deeply moving, highly eroticised but at the same time completely destroyed, defeated, alternately a young girl in limbo, then a wild little animal thirsty for desire, but also a determined woman who knows what she wants. A performance that leaves you speechless.

Jonathan Kempf plays several roles, including the initial Hamlet in Hamletmaschine, the funniest being that of Fortinbras, the Norwegian conqueror to whom Hamlet entrusts the destinies and succession because here, in Castorf's scathing vision, this Fortinbras speaks Chinese… Fortinbras 2025 is not Norwegian, but Chinese, a sarcastic, cynical and terrible nod that offers a vision of the future of Europe, where Hamlet (Paul Behren) speaks German and Fortinbras speaks Chinese. What awaits us, according to Castorf…

And then there is Paul Behren, absolutely breathtaking as Hamlet, not only in the way he modulates the text, delivering it with tenderness and violence, shouting it from the rooftops and whispering it, exhaling it, but also fascinating and almost hypnotic in his portrayal of a Hamlet who is vigorous and at the same time desperate, distraught and disoriented, but always powerful in a kind of absolute action, never weak and always on the cusp between immense tenderness and incredible hardness. Almost always on stage, frequently changing costumes, he fascinates because he is a kind of image of the total, absolute, mad and hypermnesic, hyperconscious actor. Absolutely unforgettable.

For this theatre of trial, this theatre of explosion, this cruel and stinking theatre (in the literal sense), a troupe of actors with superlative physical and vocal qualities is therefore required. a troupe in the literal, ‘Dionysian’ sense, serving the Dionysus of the evening, a Frank Castorf who seems to have found in Hamlet the syncretic locus of his entire theatre, at once an almost testamentary place and, paradoxically, one of incredible vitality. Europe may be falling apart, but what a theatrical celebration this decomposition is !

As we have already pointed out, there is a ‘revue’ aspect to it, and Adriana Braga-Peretzki's sequined costumes are no strangers to this, made of odds and ends, plastic, feathers, lace, leather, latex, velvet : none of them leave you indifferent because each one is just right for the moment it is worn and each one is theatrical in its singularity.

Other costumes, the textual costumes, where, in addition to Antonin Artaud, Heiner Müller and Shakespeare, Dante (The Divine Comedy, which Castorf staged in Serbia) and even Marius Müller-Westernhagen, the singer-actor, also jostle for position, since when Claudius appears, Hamlet ironically sings to him "Ich bin froh, dass ich kein Dicker bin " (I'm glad I'm not fat), while the other one doesn't care at all : everything slides off the powerful and self-assured…

A theatre that throws our weaknesses back in our faces

Of course, it may be irritating to see the actresses at the end with portraits of Stalin and Lenin hanging around their necks (them again…), but nevertheless, the ideologies of the 20th century sowed the seeds of the upheavals of the 21st century, as we are seeing in Eastern Europe today. It would be somewhat irrelevant to display Putin or Trump (even though Josef Ostendorf's Claudius bears a slight resemblance to Trump), who are merely ‘collateral effects’ of our wanderings and mistakes. but it is never irrelevant to recall the brutal ruptures of hope (Budapest 1956) or the gaping wounds that cannot be healed, such as the camps and the concentration camp universe : this memory is one of the indelible wounds of humanity (which seems to have forgotten this somewhat in recent times, with its soft focus on extremes and especially the far right, which is still euphemistically called populism, but which is – as we all know – nothing more than the return of the brown plague). After all, I prefer Artaud, Castorf, their theatre and their plague to the brown plague.

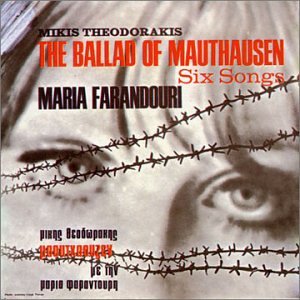

So yes, in the general disintegration of Europe, and the camps were part of that, in their reality, but also in the way their memory is sometimes distorted or erased by some, Castorf and Müller remind us that ancient mythologies give us prefigurations of this. Hamlet, as we have seen, is caught up in the wars of religion and the last convulsions of medieval beliefs : when we think of The Life of Galileo, we cannot help but think of Donald Trump and his anti-scientific struggle, because simplistic thinking is also a return to the medieval times of asserted or ‘revealed’ truths, but above all unproven truths… In short, the echoes between the troubled 16th century (let us not forget the St Bartholomew's Day massacre in France), the 17th century, which began in uncertainty, and the 20th century, ravaged by two world wars, the Holocaust and the Gulag, make the bed of the 21st century smell very bad : how then can we fail to understand Heiner Müller's allusions to the camps and how can we fail to understand that among the music in the show is Mikis Theodorakis' ballad of Mauthausen, Η μπαλάντα του Μαουτχάουζεν.

As I wrote above, Castorf is to be taken entirely or left entirely, but he is a giant of contemporary theatre and a tireless observer of the world. He is one of the few, along with Krzysztof Warlikowski, who never ceases to read and reread today's world in the light of what founded it, a 20th century marked by fascism, Nazism, Stalinism, the Shoah and the Gulag. This is exactly what Heiner Müller pointed out in Hamletmaschine.

And the quarter of the 21st century that we have just lived through heralds disturbing returns : hatred of the other, religious intolerance, totalitarianism, democratic disintegration. Theatre inevitably has a warning function, as Artaud so eloquently expresses in Le théâtre et la peste, Shakespeare in Hamlet, and Castorf in Hamlet's dismay at a world that is slipping dangerously towards the abyss. Castorf and Warlikowski, but also Wajdi Mouawad in their theatre, never cease to proclaim it, emphasise it, observe it, using literature and art, which is, after all, their function. Castorf with a dark pessimism, Warlikowski and Mouawad with a glimmer of hope ingrained in their very being. So, of course, it's easy for some to say that they are repeating themselves, that they are provoking or boring us with these old stories. The story unfolding before our eyes throws back at us what they keep telling us, repeating to us. We must not turn our heads and look away : this Hamlet, who surrenders his country to a Fortinbras who speaks Chinese (or perhaps will speak or already speaks Coca-Cola), is us, old Europe, allowing its values and humanity to be gradually eroded.

A huge and terrible moment of theatre reminds us of this in Hamburg…

Hamlet, at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus Hamburg, 25 October, 2 and 19 November, 13 December (2025), 30 April (2026), duration 6 hours, in German without surtitle.